“We’re just looking”: gazing at Bond through the ages

Daniel Craig emerging from the ocean was not as revolutionary as we think. In fact, it was more of an evolution of something that has always been there in the Bond series: an invitation, whatever our gender or sexual orientation, to look - lingeringly, even longingly - at James Bond himself.

Nearly half a century ago, Laura Mulvey pointed out something that had been literally staring cinemagoers in the face for more than half a century, since the beginning of cinema in fact: it’s far more common for women to be displayed as sexual objects in movies than it is men. Of course, women are far more likely to be sexually objectified in male-dominated mass media full stop. But with cinema being a predominantly visual medium, it’s the ideal vehicle for bringing us what Mulvey called ‘visual pleasure’.

There was a time, before the Hollywood studio system turned cinema into a production line, when more women had the opportunity to make films. 5% of Hollywood films were directed by women prior to 1930, and 20% of screenwriters were women, but most of these were squeezed out in the following decade. The result of films being made predominantly by men is that you’re far more likely to have lingering shots of drop dead gorgeous women than you are men. Historically, the small handful of gay male directors had to be very careful about shooting male physiques if they didn’t want to compromise their careers.

To their credit, most of the Bond directors - all men, none of whom identified as queer with the Bond-going public - have not shied away from displaying Bond just as much as the Girls.

It would have been foolhardy not to have showed off the physique of former bodybuilder Sean Connery and director Terence Young took every opportunity. There are many shots of Connery’s body in Dr. No, most of which are superfluous to the plot.

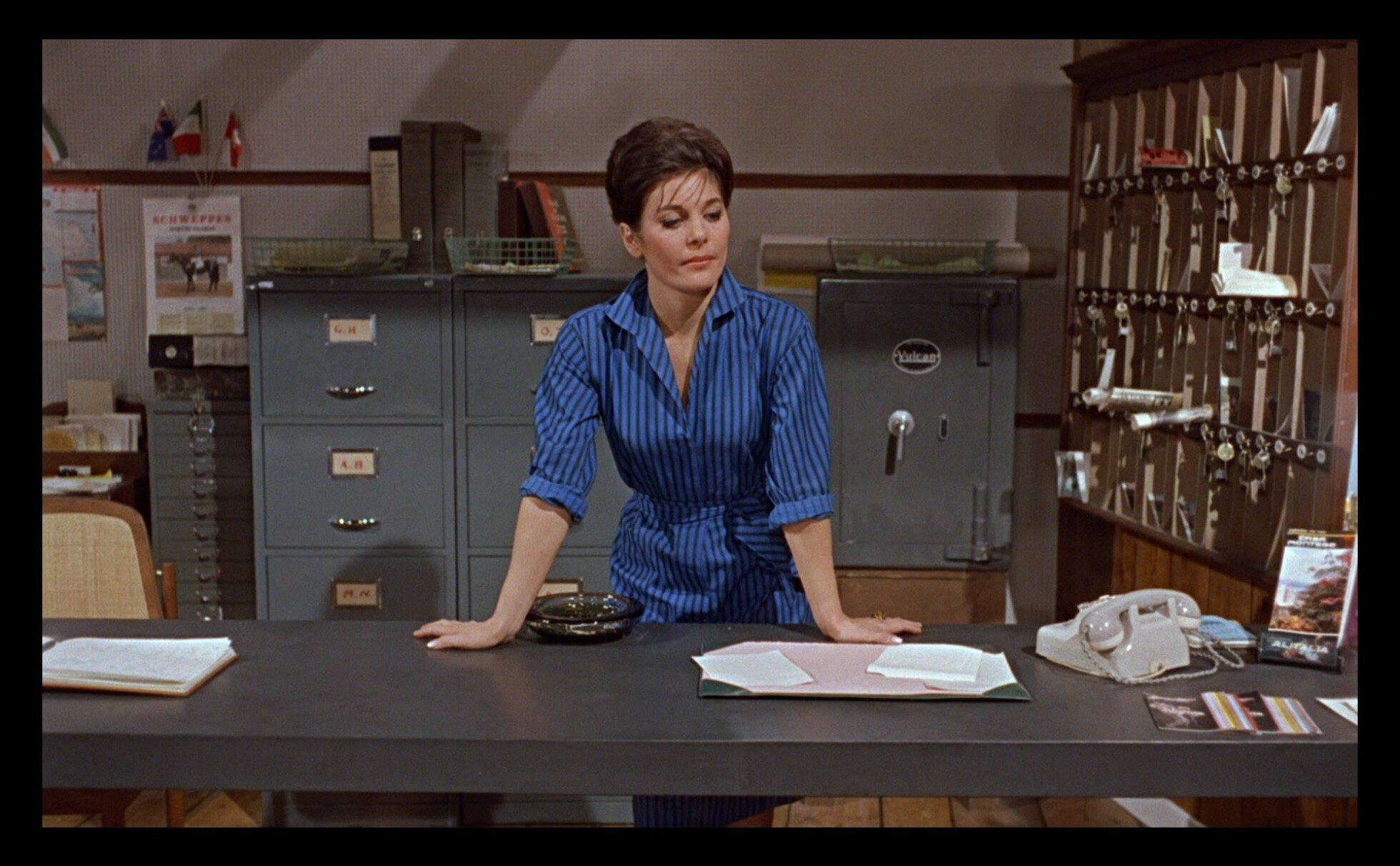

In each sequence, the camera frames Connery as the centre of our attention just as much, if not more than, Andress. The first Bond film establishes the fine tradition of everyone wanting to take a longer look at Bond. My favourite example is the receptionist of Bond’s Jamaica hotel tracking down his body as he turns away, inviting us to do the same.

Connery’s body is on display far more than his female co-star’s in From Russia With Love. As early as Connery’s second outing, Terence Young was concerned that Connery’s constant eating would ruin his physique and was always telling him to suck in his gut before he called ‘Action!’.

But whatever Connery’s waistline, he is always treated in the Bond films as a ‘visual pleasure’. That so many people deride Connery for having a ‘dad bod’ by the time he gets to Diamonds Are Forever says more about them than it does Connery, who is still a fine figure of a man and the camera does not shy away from showing it.

Did having a gay man edit the early Bond films influence the way we gaze at Bond? Probably. But it’s interesting that when Peter Hunt progressed from editor to director that we no longer saw quite as much of Bond’s body as we had been accustomed to with Connery. The production photos of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service make no secret of Lazenby’s model physique! But on screen, we see relatively little of it, with the exception of his legs. After Tracy loves him and leaves him at the hotel, he pulls on her very short robe.

And it’s true (!) that putting Bond in a kilt for forty minutes of the film was a wise move to keep the interest of those of us less inclined to derive pleasure from looking at Blofeld’s Angels of Death.

Less is Moore? After Live and Let Die, it’s rare to see Roger with his shirt off. There’s much more straight male gaze in the seventies Bond films, perhaps a reaction against second wave feminism. Live and Let Die marks the middle part of the Guy Hamilton-directed ‘bikini trilogy’, where at least one female character in the story gets paraded around in a bikini while Bond remains mostly clothed.

Not that we aren’t encouraged to take pleasure in watching Roger, but the closest we get to the pleasures we associate with Connery is A View to a Kill’s jacuzzi scene. As Bond jumps back into the bubbles after pulling a fast one on Pola Ivanova, only John Glen’s careful framing preserves Moore’s (or perhaps a stuntman’s) modesty.

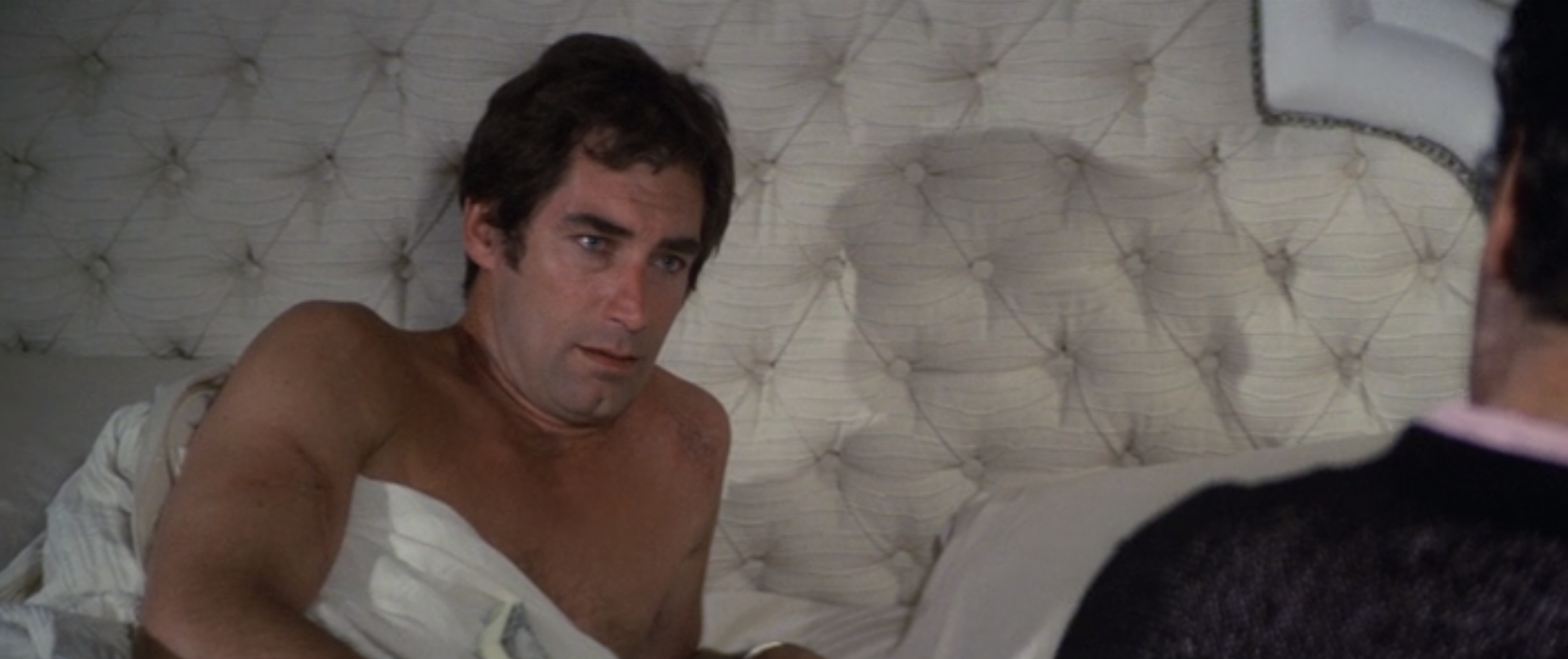

Dalton mostly keeps his clothes on. The most notable exception is notable because it happens during one of the most homoerotic scenes in the Bond canon. In Licence to Kill, Sanchez appears at the end of Bond’s bed (in Sanchez’s house… so Sanchez’s bed?), apologises for waking him up and tenderly calls him “hermano” (brother in Spanish). Bond is shirtless throughout the scene. Sanchez is clearly attracted to him and Bond presses his advantage, sowing the seed of doubt about there being “only one guy?” who is not on Sanchez’s side. Furthermore, another of Sanchez’s guys, queer-coded Perez, is seething with jealousy when he sees how close Sanchez is getting to shirtless Bond. Although we don’t get a shot from Perez’s point of view, his gaze lingers on Bond in the bed, inviting us to recall what we have just seen for ourselves.

Pierce Brosnan has sometimes attracted unfair criticism that his Bond is more like a clothes model. Such people forget how his portrayal introduced far more psychology. Also, how frequently he doesn’t wear many clothes at all. GoldenEye flirts with the audience, with some languorous shots of Brosnan swimming in a luxurious hotel pool. It’s nowhere near as eroticised as another swimming pool scene, very early in Brosnan’s career, where he appeared as an IRA assassin luring his gay male victim to his demise (1980’s The Long Good Friday). But in GoldenEye, Bond believes he is there to meet a man, Janus. So are we to assume that Bond is going to rely on his body to catch Janus off his guard?

Tomorrow Never Dies has some gratuitous gazing action which seeks to helps to redress mainstream media’s gender imbalance. When Bond and Wai Lin shower off post-bike chase, it’s him the camera tracks, not her. Brosnan and his four Bond directors certainly didn’t forget the first rule of mass media: give the people what they want!

So much has been written about Daniel Craig emerging from the ocean and with good reason. Queer author Meg-John Barker observes that, “This is a queer moment in its invitation to view a male body with a desiring gaze usually directed at female bodies in mainstream media”.

But the scene is not as revolutionary as many believe it to be. Yes, Craig’s hulking frame is almost a parody of masculinity, reminding us that gender is a performance, an effect that perhaps has been diminished a little since the film’s release by Marvel making a muscle-encrusted male de rigeur.

Remember though, that Sean Connery’s Bond in Dr. No hardly had an ‘everyman’s’ figure. And while subsequent Bond actors weren’t always as hench as 007’s first cinematic iteration (or even the henchmen) they have always been displayed as visual pleasures of one form or another.

Daniel Craig emerging from the ocean was more of an evolution of something that has always been there in the Bond series: an invitation, whatever our gender or sexual orientation, to look - lingeringly, even longingly - at James Bond himself.

Thanks to Meg-John Barker, Mark Cousins (Women Make Film, The Story of Looking) and Laura Mulvey, whose work has inspired this piece.