“Something to do with Cuba”: missiles, man love, mojitos and Fleming’s fearful fascination

Despite neither Fleming nor a Bond film crew having ever visited the Caribbean’s largest island, it plays a key role in numerous 007 books and films. Fleming was fascinated by but fearful of Cuba, his feelings towards the place shifting dramatically across the book series for reasons that have never been clear. And the way the country has been shown on screen raises some interesting questions around representation. After decades of wanting to visit, I headed to Havana in search of ‘the real Cuba’.

This article is also available as a podcast, wherever you get podcasts.

In his novelisation of Die Another Day, Raymond Benson begins the chapter in which Bond arrives in Havana by stating: “Bond felt ambivalently about Cuba”. He goes on to unpick Bond’s ambivalence a little. Benson/Bond observes that while Cuba has, on the one hand, “great natural beauty” and “preserves many architectural treasures” it is, on the other, “stifled by its lack of personal freedom”. It is “a hotbed of intrigue and artifice” with a “pervasive air of mistrust and suspicion”. The perfect milieu for a spy adventure then, but a suitable setting for a romantic getaway?

I’m glad I waited to read Benson’s book until I was already on a flight to Havana and not when I was still in the Manchester International departure lounge, else I might not have even made it on to the plane.

Cuba is a place my husband and me had wanted to visit since we got together, 15 years ago, although neither of us could tell the other why. A few of our friends had gone and had a good time. Two had even gone there on their honeymoon over a decade before. We had seen plenty of photographs of Cuba - principally crumbling buildings and automobiles seemingly time warped from the 1950s - and it looked like a place with history, culture and good cocktails (the latter especially being a prerequisite for us). But neither of us could do much better, when people asked us why we wanted to go to Cuba, than “there’s just something about it”. As it happens, the curiously imprecise ‘something’ is the word that sprang most readily to mind when Ian Fleming wrote anything about Cuba, a place he was fascinated by but fearful of actually visiting. But we’ll come on to that in a minute. For now, let’s stay with Bond’s arrival in Havana…

You know the shot. THE shot from Die Another Day. The one that establishes Bond has travelled from Hong Kong to Havana: the pan from a couple snogging on the sea wall (practically eating each other’s faces off, such is their Latin passion!) to Pierce Brosnan affecting nonchalance as he walks towards the camera in a blue floral shirt. So iconic is this shot that artist Billy Robertson chose this out of all the shots in Die Another Day to represent the film in his 60 Years of Cinematic Bond series.

In the film, we don’t really need the subtitle telling us we’re in Havana. If we didn’t get it from the visuals, David Arnold’s score clues us in. Arnold captured the music’s Cuban energy by getting the musicians (and himself) drunk on tequila. Although a more apt libation would have been rum, the finished music works a treat, brazenly announcing: WE’RE IN HAVANA.

Except… we’re not in Havana, but Cadiz in southern Spain. The US trade embargo made filming in Cuba itself impossible. Cadiz has stood in for Havana for an earlier Bond actor: Sean Connery was directed by Richard Lester there for the less-than-imaginatively titled 1979 adventure thriller Cuba.

Previous stand-ins for Cuba have included Puerto Rico for the closing scenes of GoldenEye and RAF Northolt, the airbase in West London, for Octopussy. The location of the Octopussy pre-credits sequence is not explicitly identified as Cuba. Some contend that it’s supposed to be Argentina because of the Falklands War of the previous year. But it’s uncharacteristic of the Bond film producers to be quite so on the nose with sensitive geopolitical events. Relations between Britain and Argentina were still very raw in 1983. While it’s entirely possible that the Latin American state depicted on screen is supposed to be an amalgamation of several real countries, the presence of a Fidel Castro lookalike, imported palm trees (Cuban national symbol) and Bond telling his female assistant he will meet her in Miami (Florida is less than 100km away from Havana as the Acrostar jet flies) has always led me to assume it’s Cuba.

No Time To Die’s Cuba sequence was shot on soundstages after the filmmakers were denied permits by the Cuban authorities, apparently because of the way the country was portrayed in the script. Shooting at Pinewood also allowed for greater control of a scene with a lot of moving parts, not to mention ballistics. No Time To Die’s Cuba action takes place not in Havana but Santiago, on the other side of the island to Havana, 15 hours away by train.

The ‘Cuba’ we see on screen in four Bond films is a distortion of reality. In each case, it’s an exaggerated and stereotypical portrayal: real Cuba turned up to 11. One could say this of most Bond locations. With precious little screen time to establish a setting, the Bond films excel at throwing at the audience everything they associate with a place. One example: when I was walking along the Malecon (the sea wall), attempting to channel some Pierce Brosnan nonchalance, I did not see heaving crowds of people fishing and kissing with Latin passion. Although the Malecon is a popular spot for anglers and couples, they are spaced out over a distance of many miles, not concentrated as in the film. Not in my favour was the fact that it was a unseasonably cold and windy day and the waves crashing against the wall were getting dangerously high. Being the only person demonstrating British fortitude in a short sleeved shirt, I did attract some curious looks from the locals who were more appropriately dressed for the weather.

Cuba is shown in most of the films to be a safe haven for criminals, a throwback to an earlier period in Cuba’s history. No Time To Die has Cuba being the venue for Blofeld’s birthday party, a Bunga Bunga orgy for SPECTRE’s agents. No wonder the Cuban government refused the filmmakers permission to shoot there. Die Another Day turns Havana’s coastal fortress El Morro into a gene therapy clinic for wealthy criminals (including a racist South African who uses the name of Cuba’s leader to make a penis pun). And who knows what deal Alec Trevelyan, a vengeful bank robber when it comes down to it, struck with Castro to allow him to build a hulking great radio telescope on the island?

Before going to Cuba myself, my main visual reference for the country was the 1959 adaptation of Graham Greene’s novel, Our Man In Havana, which was actually shot in Cuba just two months after the fall of despotic dictator Fulgencio Batista and rise of Castro. Castro’s new government granted the filmmakers the necessary permits although 39 changes to the script were required. Castro was disappointed that the film was not even more critical of Batista’s era but he still turned up on set to meet stars Alec Guinness and Maureen O’Hara. I had also seen ‘Cuba’ in The Godfather Part II, although that was shot in Dominican Republic, the country which most commonly doubles Cuba.

Despite appearing in several Bond films, no shots of actual Cuba have appeared in a James Bond film, so what would reality be like? I was curious to see if it matched up to my Bond-influenced fantasies.

My secret agent fantasy life is not difficult to sustain when a fact of my daily existence is me having to perpetually survey my environment for threats. Growing up gay is great training for a career as a spy. But it’s exhausting having to constantly look over my shoulder in case of a homophobic attack, and this is not something anyone wants to be doing when they’re on holiday.

It enrages me no end that whenever my husband and me are planning a holiday anywhere we have to conduct a risk assessment because of who we are. There are still more than sixty countries where it is illegal to be gay, including several key Bond locations. Many of these places - such as Jamaica - criminalise homosexuality because of British colonial laws still on the statute books from centuries before.

Even those countries where there are no laws against us may be hostile.

Would my husband and me feel stifled (going back to Benson’s verb choice) by Cuba’s purported lack of personal freedom because we were gay? Before we booked our trip, we performed the necessary background checks on the status of LGBT rights and how we could expect to be treated…

The legal status of queer people in Cuba for much of the 20th Century is somewhat open to interpretation. In the 1930s, a law descended from Spanish rule criminalised ”ostentatious displays of homosexuality in public" (so, in private was fine?) and “habitual homosexual acts” (as long as you only had sex with people of the same sex now and again then that was okay?).

In the decade following the 1959 revolution, gay men were sent to labour camps, along with society’s other undesirables. This has subsequently been spun as a way of protecting gay men during their compulsory military service, the less-than-convincing defence being that gay men might have been discriminated against by the straight men they were serving with unless they were segregated. Horrendous as this no doubt was, we should be wary of looking down our noses: comparable practices have existed in countries who pride themselves on more impressive human rights records, including my own.

Being queer in Cuba continued to be dangerous for the decades that followed the revolution. You get a snapshot of this from the memoir Before Night Falls, by gay Cuban poet Reinaldo Arenas, adapted into a film with Skyfall’s Javier Bardem in the lead role.

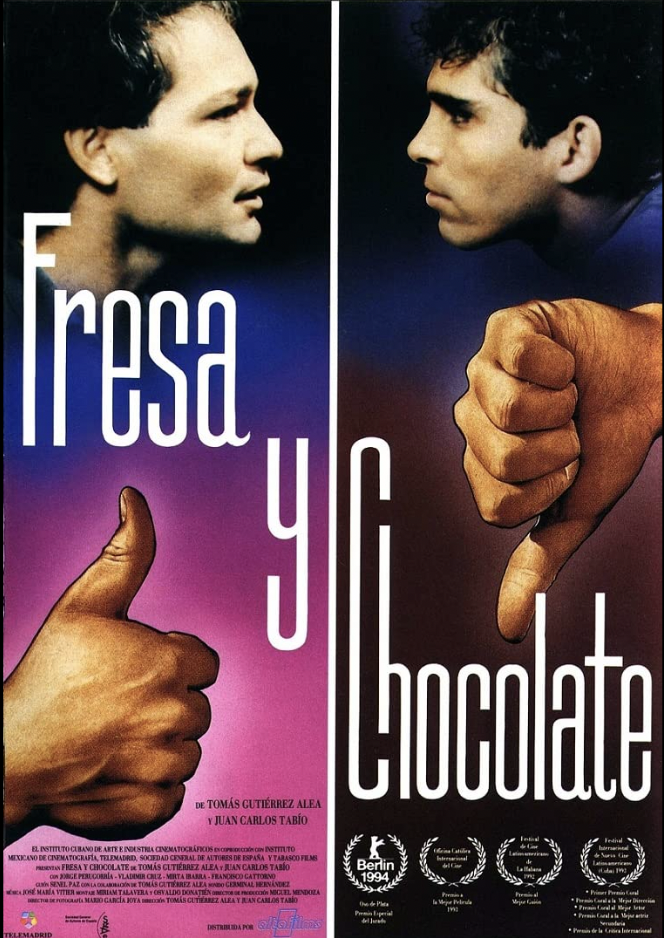

It was a 1993 film made in Cuba itself that has been credited with opening up the national conversation about the treatment of gay people in the country and paving the way for reform. Although Strawberry and Chocolate is set in 1979, it provided pointed commentary on the inequalities in the Cuba that remained in the present day. The story concerns the development of a friendship between David, a straight-identifying man, and Diego, who is openly, flamboyantly gay. That synopsis makes it sound like twee Oscar bait. And in fact it’s the only Cuban film ever to be nominated for an Oscar. But the film is very strong on every level and surprisingly nuanced. Ambiguities abound, not least surrounding David, who may not be as straight as he maintains. Even more ambiguous is David’s hunky roommate whose homophobia may be masking a secret. Is this a critique of those men who conflate nationalistic fervour with being macho? The film cleverly avoids confirming or denying our suspicions, allowing us to make up our own minds - or be satisfied with all possibilities.

The film’s title alludes to the gender stereotyping of ice cream flavours: straight men choose chocolate and gay men order strawberry, because that’s what women prefer. At the time of the film’s production, these were the only two ice cream flavours available in Cuba - if you could even get it. Strawberry and Chocolate was released in one of the most challenging periods of Cuba’s history, when food was scarce. Even so, it helped to make gay rights a government priority. By 2010, even Fidel Castro himself was telling the foreign press that his regime got its treatment of gay men wrong following the revolution: “If anyone is responsible, it is me.”

The most powerful advocate for LGBTQ+ rights within the present government is none other than the daughter of Fidel’s brother Raul, who was president himself after Fidel retired. Mariela Castro leads Havana Pride every year, the first event having taken place in 2008. In the same year, gender reassignment surgery was made freely available by the state. In 2012, Adela Hernández was elected to the council of Caibarién in the Villa Clara Province, becoming the first transgender person ever elected to political office in Cuba. Workplace discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is now illegal. In September 2022, same sex marriage was legalised following a referendum. In the context of the Caribbean, Cuba is - according to Amnesty International - “one of the most advanced countries in the protection and promotion of the rights of LGBTI people”. Some social stigma remains, as it does in almost all (if not all) countries, but for our part, we didn’t experience any of it. This might not be a surprise considering we were very obviously tourists (more obviously in my case - while my husband occasionally passed as Cuban I didn’t stand a chance with my ginger hair and blue eyes). But we don’t take our privileged status as tourists for granted. We have visited many countries where, although we have been protected legally, we have made to feel uncomfortable walking down the street holding hands. We didn’t get that with Havana, even when we were miles away from the parts of the city popular with foreign visitors.

While queerness is not as visible in Havana as in some other large cities we’ve visited, it hardly feels closeted. We saw same sex Cuban couples holding hands, trans people walking down streets unharassed and numerous rainbow flags. One of the grand hotels lining Havana’s bustling Central Park was festooned with them. We popped in for drinks and discovered the hotel was part of an international chain which targets the LGBTQ+ market. You don’t have to be queer to stay there of course. Their signage featured the proclamation “We are heterofriendly”, a cute reversal of all-pervasive heteronormativity. Such small gestures make a big difference to queer travellers, helping us feel welcome and not like undercover agents fearful of having our covers blown at any moment.

Bottoms and bones, tourists and terrorists

Ian Fleming had some unconventional leanings of his own, politically speaking at least. In The Spectator in October 1959 he stated:

“I am a totally non-political animal. I prefer the name of the Liberal Party to the name of any other and I vote Conservative rather than Labour, mainly because the Conservatives have bigger bottoms and I believe that big bottoms make for better government than scrawny ones.”

He claimed his own personal hero was Sir Alan Herbert. Not, presumably, because of the size of his posterior. Fleming liked Herbert because, as an independent MP, he “stayed out of the muddy red and blue stream”. But Fleming also said he had “the affectionate reverence for Sir Winston Churchill that most of us share”. Fleming perhaps makes a sweeping assertion that “most” people shared a reverence for Churchill. The Conservative Prime Minister led the UK through the Second World War with ‘Bulldog spirit’ but then lost the general election, two months after VE Day, in a landslide to the Labour party.

Churchill is framed in heroic terms several times in the Bond books, most notably in From Russia, With Love. It’s never clear what Bond himself felt towards Churchill but, in Fleming’s final interview, for Playboy magazine, he said Bond’s own politics would be “left of centre”, so maybe he would not have been as reverential as Fleming himself.

In his novelisation of Die Another Day, Raymond Benson states that Winston Churchill had once said of Cuba that he “might leave his bones there”. The quote comes from a volume of Churchill’s autobiography, written in 1930, recollecting his adventures in Cuba thirty five years previously. Here’s the quote in context:

“When first in the dim light of early morning I saw the shores of Cuba rise and define themselves from dark-blue horizons, I felt as if I sailed with Long John Silver and first gazed on Treasure Island. Here was a place where real things were going on. Here was a scene of vital action. Here was a place where anything might happen. Here was a place where something would certainly happen. Here I might leave my bones.”

Winston Churchill was barely into his twenties when he visited Cuba for the first time. He was seeking to make his name as a soldier and war correspondent. But most of all, he travelled to escape boredom. Like Fleming (and his most famous creation, 007), Churchill was terrified of being bored. Boredom could bring on or exacerbate mental difficulties. For Fleming (and Bond), inaction brought on ‘accidie’, a lethally depressive lethargy. Churchill famously personified what we would probably diagnose today as manic-depression as his ‘black dog’. The best way to keep the black dog at bay was to not allow himself to become bored.

Fortunately for Churchill, Cuba in 1895 was far from boring. The Cubans were winning their fight to throw off centuries of Spanish rule (they would ultimately succeed, with support from the US, in 1898). Churchill’s reports from Cuba paint the Cuban insurrectionists as freedom fighters rather than terrorists.

Freedom fighter/terrorist is not as neat a dichotomy as it may first appear. Bond himself takes aim at the binary in Die Another Day:

Raoul: I love my country, Mr. Bond.

Bond: I'd never ask you to betray your people. I'm after a North Korean.

Raoul: A tourist?

Bond: A terrorist.

Raoul: One man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter.

Bond: Zao has no interest in other people's freedom.

Churchill was all for people fighting for their freedom, just as long as things didn’t go too far or conflict with British interests. Historian and former diplomat David Stafford encapsulates the apparent contradiction:

“During the Second World War [Churchill] would lend his enthusiastic support to movements of national revolt against Nazi occupation, such as the Yugoslav partisans and the French Maquis. But he adamantly opposed those he considered to be ‘extremists', such as the Greek partisans. Significantly he regularly condemned them as `banditti' -- the contemptuous term used fifty years before by his Spanish hosts [in Cuba].”

One man’s banditti are another man’s freedom fighters!

Churchill recognised that “Armed guerrillas fighting with the support of the people could thwart the ambitions of even a great and powerful empire”. This is what led him to form the Special Operations Executive during the Second World War, one of the intelligence services which Ian Fleming would liaise with and which Fleming’s older brother Peter would be a member of.

Fleming’s fearful fascination

Considering that Cuba was on Fleming’s doorstep whenever he was staying in Goldeneye, it’s curious why he never himself visited Jamaica’s much larger island neighbour. Cuba certainly seemed like his kind of place. When I asked Fleming’s biographer, Andrew Lycett, about this he said:

“It’s interesting about Fleming and Cuba. He was clearly fascinated by it. You’d have thought he might even have gone there pre-the Revolution, i.e. after he was first in Goldeneye in 1948 at least till 1953, and perhaps later. It’s almost as if he was fascinated, but also slightly afraid of it.”

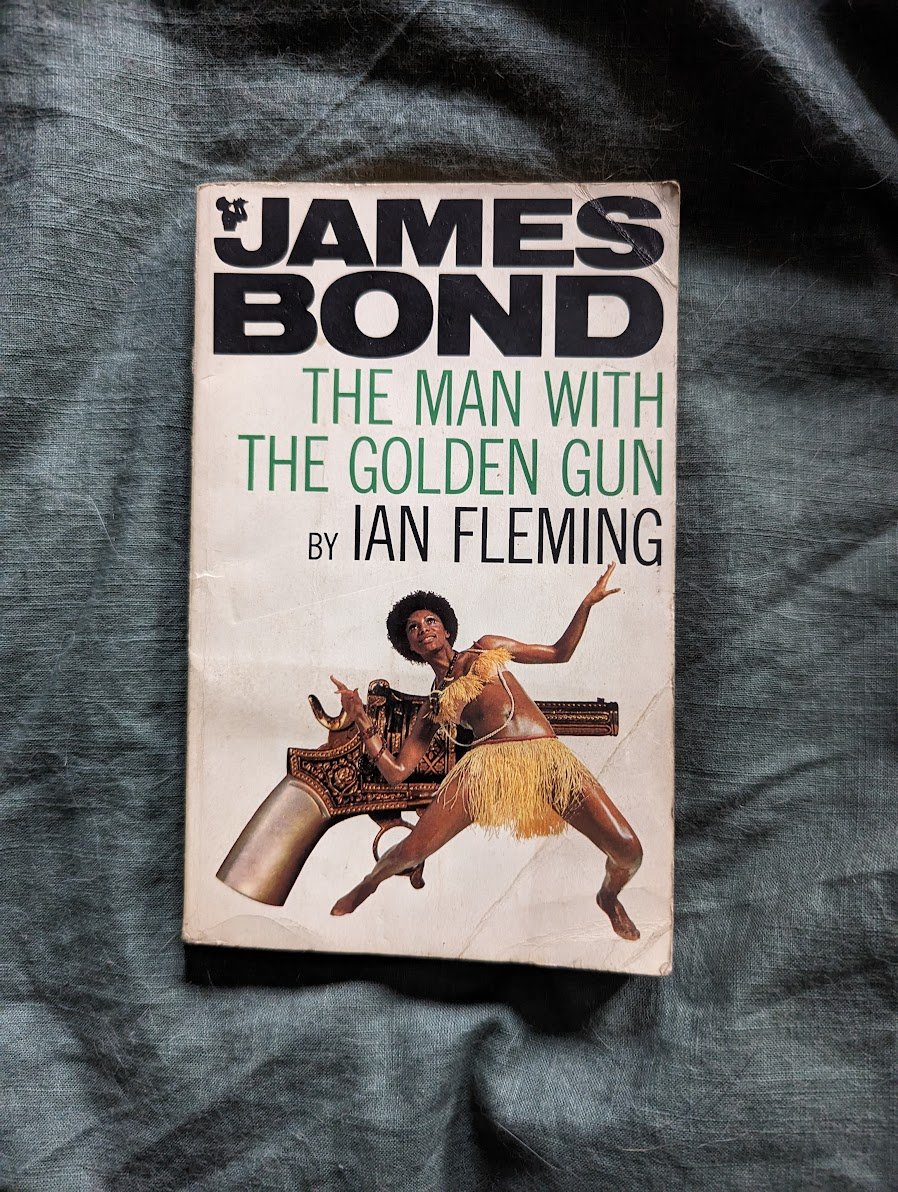

While Fleming lived so much of his life vicariously through Bond, he never sent Bond to Cuba in his stead. And yet, his Bond novels are crammed with references to Cuba. From first Bond book to the last, from 1953 to 1964, Casino Royale to The Man With The Golden Gun, the novels chart the changing fortunes of - and feelings towards - Cuba across this turbulent decade.

The first reference occurs as early as the first chapter of Casino Royale. When M sends Bond additional funds for his gambling mission, he cables the information using the cover of a Jamaican business exporting Cuban cigars. Casino Royale was published in April 1953, a time when foreign businesses could still thrive in Cuba. In March 1952, while Fleming was redrafting his ‘spy story to end all spy stories’, former president Fulgencio Batista had seized power in a coup d’etat. For the next seven years, Batista tightened his grip on power by any means - often bloody - and filled his pockets with backhanders from foreign investors, including the mafia. His dictatorship did not remain unopposed for long. Just over a year later, only three months after the publication of Casino Royale, the revolution began.

Cuba was not exactly a stable place for much of the 1950s. It’s fascinating to see this somewhat fluid situation reflected in the pages of the Bond books.

In the second novel, Live and Let Die, Bond discovers that Mr Big’s yacht regularly puts in at Havana and he is using Cuba for “running red agents all through the Caribbean”. Real-life Cuba at this time was not exactly a haven for communists. Although Batista had been supported by the Communist Party of Cuba during his first presidency in the early 1940s, he was virulently anti-communist during his second. Of course, Mr Big and his interests are protected by his vast wealth, like so many other nefarious criminals who used Cuba as their base of operations.

The political situation in Cuba is merely a backdrop to Live and Let Die. Of more interest are the references to Cuban culture, reminding us of the pre-revolution cultural exchange between Cuba and the southernmost points of the United States. After taking the train to Florida, Felix suggests he and Bond take Solitaire for dinner at a Cuban restaurant, which he considers “the best restaurant on the whole coast”. When Bond checks into a motel “the middle-aged couple that owned the place were listening to late rhumba music from Cuba”. Later, when Bond takes a plane to Jamaica, in pursuit of Mr Big and the recaptured Solitaire, he looks out of the window to see “the twinkling mother-of-pearl lights of Havana, so different in their pastel modesty from the harsh primary colours of American cities at night.” Upon landing at his destination we are told:

“Bond knew Jamaica well. He had been there on a long assignment just after the war when the Communist headquarters in Cuba was trying to infiltrate the Jamaican labour unions.”

This is a fleshed out version of the backstory alluded to in Casino Royale, where Fleming drops in to the first chapter that “Bond had once worked in Jamaica” but doesn’t elaborate. Live and Let Die reveals that the nature of this work was countering Communism in Cuba. Was Bond indirectly helping Batista’s regime? It would be somewhat unpalatable to think of Bond supporting a dictator who murdered 20,000 of his own people in just seven years, usually after having them horribly tortured.

With the third novel, Moonraker, being set entirely in Britain, it’s perhaps not surprising that it contains only a brief reference to Cuba. When M and Bond meet Sir Hugo Drax to challenge him at cards, they find Drax and his metal broker, Dreyer, smoking Havana cigars. Cuban cigars were not embargoed by the United States until 1962, seven years after Moonraker’s publication and Cuban exports have never been embargoed by the UK government. However, Cuban cigars would not have been cheap so Drax and company smoking them signifies their wealth. Perhaps it is also intended to provide covert Nazi Drax with additional cover as a respectable figure of the British Establishment. British bulldog Churchill was not only a fan of Cuba itself but also a big consumer of Cuban cigars. As it becomes clearer and clearer that Drax is a villain, Fleming has him switch to small cigarettes, reflective of his diminished masculinity and Britishness. Rarely is a cigar just a cigar. [It has to be said that cigars do not carry the same gender associations in Cuba, where you’re just as likely to see a woman puffing away on the street as you are a man.)

In late 1957, while still working for the Sunday Times, Fleming asked a novelist he admired, Norman Lewis, to fly to Cuba to find out if Castro’s revolt was likely to succeed. He told Lewis he believed that Ernest Hemingway, a writer Fleming idolised, had insider information from Castro’s camp. As it turned out, Hemingway had no privileged insights, but the episode highlights how fascinated Fleming was with the political situation in Cuba.

Courtesy of his regular winter jaunts to Jamaica, Fleming must have become accustomed to seeing Cuba through a plane window. He has Bond repeat the experience in Dr. No. Unlike in Live and Let Die where Bond sees Havana from the aircraft after dark, this time Bond looks down to see the “green and brown chequerboard of Cuba”. At the end of that mission, with Dr. No and his organisation destroyed, the local Police Superintendent seconds Bond’s supposition that No’s henchmen have probably escaped to Cuba. This is logical considering the location of No’s fictional island, Crab Key: Fleming places it off the northern coast of Jamaica, sandwiched between Jamaica and Cuba.

Dr. No was the final Bond novel to be published (March 1958) while Batista was still in control of Cuba. Even so, in the next novel, Goldfinger, we are told that one of Goldfinger’s mafia conspirators, Jed Midnight, has arranged for the failed gold robbers to hide out in Havana. Goldfinger was written in 1958 but published in March 1959, three months after Castro ousted Batista. However, the action of Goldfinger takes place in May-June 1957, meaning the fictional mobsters could have still been assured of a very warm welcome. The same would have been true even had Goldfinger been set eighteen months later; it wasn’t until several years into his Prime Ministership that Castro would finally rid Cuba of its mafia influence.

Although published in the May 1959 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine, the short story Quantum of Solace takes place in January-February 1958, eleven months before Castro and company sent Batista packing. Bond’s mission is to disrupt the flow of weapons getting to the revolutionaries from British colonies. Bond doesn’t want to do the job. We are told “his sympathies were with the rebels”. But the British Government is profiting from exporting goods to Batista’s government. Reluctant to kill the revolutionaries, Bond completes the mission by blowing up their boats instead. This setup is used to frame the story: the bulk of the ‘action’ concerns emotional violence inflicted within a marriage. After hearing the governor’s story of man and wife inflicting great pain on each other, Bond reflects that the “violent dramatics” with the boats seem “hollow”. And indeed, Bond’s explosive actions have little impact on the success of the revolution, something that would have been appreciated by Quantum of Solace’s first readers, living in a world where Castro won. Fleming uses real-life heroic deeds to reinforce the futility of Bond’s “adventure strip” heroics.

As if he felt the need to confirm where Bond’s (and our) sympathies should lie, Fleming makes the murdering villains of his short story For Your Eyes Only “gangsters from Havana”. The story appeared in print in 1960 but is set in September-October 1958, just months before Batista fled. M tells Bond that they haven’t been able to get any information out of Batista’s people “but we've got a good man with the other side--with this chap Castro. And Castro's Intelligence people seem to have the Government pretty well penetrated.” With the benefit of hindsight, Fleming has M add “It looks as if Castro may get in this winter if he keeps the pressure up.”

Batista’s despotic reign ended on New Year’s Day 1959 after revolutionary forces, led by Che Guevera, took the city of Santa Clara, Cuba’s fifth largest city, 260km from Havana. Realising the writing was on the wall, Batista flew to Portugal. He lived for a while in Estoril an important location for the film of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Although the story of Thunderball began life in the summer of 1958, it was the first Bond adventure to be written (early 1960), published (March 1961) and set (May-June 1959) after Castro got in. Despite most of the story taking place in the Caribbean, Cuba barely warrants a mention. Petacchi is fed a story by SPECTRE (which he doesn’t believe) that he’s being paid to hijack the plane by a “Cuban revolutionary group who wanted to call attention to its existence and aims”.

It’s at this point that Cuba conspicuously disappears from the Fleming Bond universe. In the period between For Your Eyes Only and The Man With The Golden Gun, Fleming produced three novels and several short stories. But Cuba disappears from view. This is somewhat ironic considering that, in the real world, Cuba had very much taken centrestage. Immediately following the 1959 regime change which put Castro in charge, the Soviet Union had little interest in getting involved with Cuba. That was, until the United States started to see Cuba as a threat. If other Latin American states saw Cuba being successful, would they also turn communist? Tensions escalated considerably when the Soviets began installing medium range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) and nuclear warheads on Cuba which, if made operational, would have made it easy to deliver nuclear payloads to the US mainland, potentially triggering nuclear apocalypse.

Military historian Jeremy Black observes that the anxiety about the Soviets potentially using Cuba as a base for launching MRBMs and not being able to retaliate if they were fired upon may have influenced the missile toppling plot of the film version of Dr. No. Early versions of the script contained references to a Cuban agent, although these were dropped and SPECTRE’s role pushed to the fore. Nevertheless, Director Terence Young attributed a chunk of Dr. No’s success to the film being released in the UK during the same week as October 1962’s ‘Cuban Missile Crisis’.

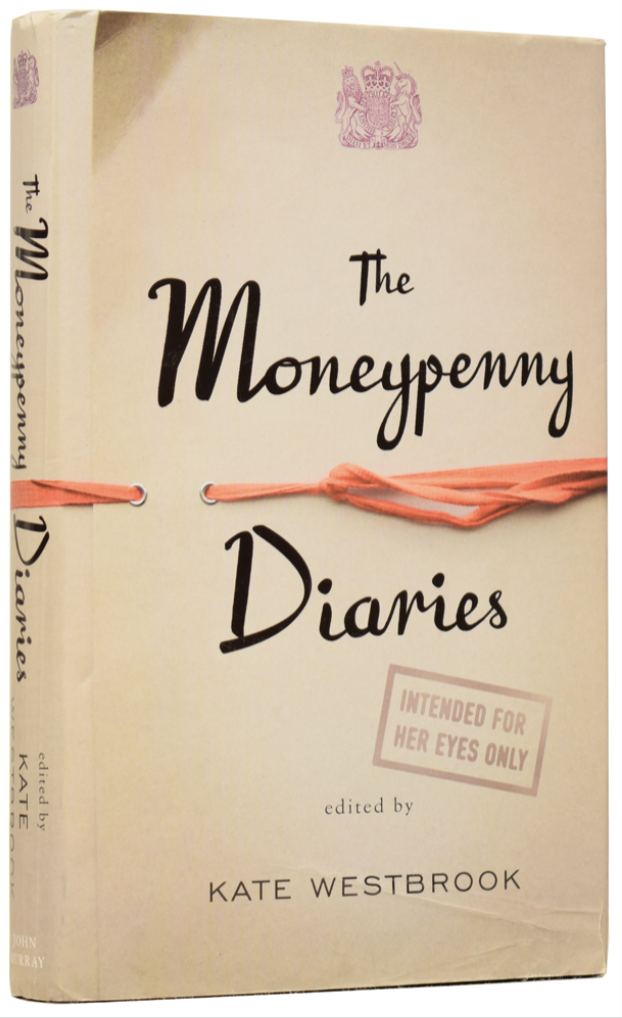

Called merely the ‘October Crisis’ by Cubans themselves, it gets a passing mention in Fleming’s The Man With The Golden Gun, published in 1964. However, in 2006, Samantha Weinberg (writing as Kate Westbrook) wove it into the whole second half of her first volume of The Moneypenny Diaries, Guardian Angel. With Soviet interest in Cuba increasing, Bond infiltrates the country via Castro’s home city of Santiago (later to feature in No Time To Die), moves west to Havana and stays at the Las Vegas-inspired Hotel Riviera (built by mobster Meyer Lansky in 1957). After being captured, Bond is rescued by Moneypenny and they fly back to England together. Both of them then return to Cuba to find evidence that MRBMs are being installed. After a daring escapade to obtain photographs of the missiles, Moneypenny recuperates at the Sevilla, the hotel where the hero of Graham Greene’s Our Man In Havana is recruited into the British Secret Service.

Fleming’s feelings towards the Castro-led revolutionary regime changed a lot in the four years between For Your Eyes Only and The Man With The Golden Gun. Andrew Lycett has speculated that it might have had something to do with Fleming moving in CIA circles and having dinner with President John F Kennedy himself:

“I think you are right to point to a changing in his views about the place. Was his visit to Washington in 1960 when he met with CIA types anything to do with that? I’ve always thought his idea of suggesting that beards were radioactive and emasculating was ludicrous, and I can’t imagine why it was taken seriously. Maybe the Americans were desperate at the time, but I would have thought they were a bit more sophisticated than that.”

The beard thing was one of Fleming’s famous flights of fantasy. Convinced that Castro’s iconic facial hair was the reason for his success, Fleming told President Kennedy that the US government should put it about that beards attracted radioactivity and made one infertile. That would lead (somehow!) to Castro shaving it off and falling from power because he would no longer have a distinctive look.

In an interview with Canadian TV recorded early in 1964 but not broadcast until five days after his death, Fleming did not mince his words, labelling Castro a “lunatic”. Perhaps Fleming’s own feelings about Cuba’s leader were just reflective of wider public sentiment, the Cuban government’s fraternisation with the Soviets making them more difficult to side with. The freedom fighters, who M had relied on for reliable intelligence only four years before, were now starting to look more like terrorists to many.

Fleming’s final novel, The Man With The Golden Gun is the Bond book with by far the most interest in Cuba. It even features a Cuban Double-0.

While a free-lance assassin, Scaramanga is mainly under K.G.B. control, receiving his orders via Havana’s Department of State Security. At the beginning of the novel, M reads in Scaramanga’s dossier that, after killing a notable mobster in a rival gang, Scaramanga laid low by travelling the Caribbean making investments on behalf of mob bosses and corrupt dictators, including Cuba’s dictator Batista. Unlike Batista, Scaramanga doesn’t flee Cuba when the revolution succeeds. Indeed, M’s dossier tells us that although Scaramanga was pretending to work for Batista, he was working against him, being an undercover agent for Castro the whole time. When the revolution came, Castro appointed him as their state assassin. In other words, he’s the Cuban James Bond. The blunt instrument of the Cuban government.

Although Scaramanga’s motivations are murky, his main objective is to destroy Jamaica’s sugar crop to advantage Cuba. Fleming tells us, via Mary Goodnight (who has read it in Jamaican newspaper the Gleaner) that Jamaica’s sugar is serious competition for Cuba. Although Goodnight claims to not understand the situation in full, she accurately summarises, for Bond’s and the reader’s benefit, the stakes for the Cuban people in the early 1960s:

“So it's worth Castro's trouble to do as much damage as possible to rival sugar crops. He's only got his sugar to sell and he wants food badly. This wheat the Americans are selling to Russia. A lot of that will find its way back to Cuba, in exchange for sugar, to feed the Cuban sugar croppers."

Accurate as she is here, Goodnight doesn’t get everything right. She prophesies that: “I don't think Castro can hold out much longer. The missile business in Cuba must have cost Russia about a billion pounds. And now they're having to pour money into Cuba, money and goods, to keep the place on its feet. I can't help thinking they'll pull out soon and leave Castro to go the way Batista went.”

As we now know, the Soviet Union did not pull out. But when it collapsed at the end of the 1980s, it took Cuba’s market for sugar with it. In turn, the Soviet food supply to Cuba dried up and, with sanctions still in the place from the USA, life became very hard for the Cuban people.

The detail of Scaramanga’s sugar monopoly plot is difficult to discern, perhaps as a consequence of Fleming having passed away before being able to redraft the novel. It concerns getting Rastafarians high and having them firebomb the plantations… and maybe it’s best to just leave that there! For me, the plot isn’t the point. The Man With The Golden Gun has always been a novel more interested in characters. Maybe even if Fleming had lived long enough to add his hallmark telling details, he would not have added much to the plot. Fleming perhaps leaves us a clue to his intentions when Goodnight asks Bond about his mission: “Bond told her vaguely that it was "something to do with Cuba."” Interestingly, this is the exact phrase Fleming has Live and Let Die’s Solitaire use when trying (and failing) to explain to Bond the exact nature of Mr Big’s involvement with Cuba. Similarly, the heroine of For Your Eyes Only, Melina Havelock, tells Bond that she travelled to Cuba attempting to track down her parents’ murderer. But by the time she had a lead “‘'He had left Cuba. Batista had found out about him or something.’” The obliqueness of “something” suggests that trying to pin down with any precision anything to do with Cuba is a fool’s errand.

The way Fleming uses “Cuba” bears comparison with Robert Towne’s use of “Chinatown” in his screenplay to the 1974 film noir directed by Roman Polanski: Chinatown/Cuba are not just places but metonyms for things which are essentially unknowable. (“Forget it Bond. It’s Cuba.”)

Brendan Sainsbury, author of the Lonely Planet travel guide my husband and me relied upon during our trip to Cuba, attempts to pin down in words Cuba’s mercurial quality:

“No matter how many times I visit this plucky Caribbean nation… I still return home with more questions than answers… One day nothing adds up, the next day everything makes sense.”

A similar sentiment was expressed by Yilian, the city guide we enlisted on our first day in Havana. I couldn’t help thinking of her as our own Agent Paloma. Like Paloma, she hailed from the city of Santiago (unlike No Time To Die actor Ana de Armas who grew up in Havana). Antony, Yilian and me were stood beneath a towering marble statue of Jesus, erected only a week before Castro took power. Castro famously proclaimed Cuba to be an atheist state but did nothing about the huge statue of Jesus, clearly visible from any rooftop in Havana. I was reluctant to ask Yilian anything that would cause her discomfort but I ventured that I thought it was interesting that the giant Jesus was not torn down by the atheist regime. Yilian knew what I was getting at and said it was complicated… but everyone loved the statue, whether they were religious or not. One thing everyone agreed on, she explained, was that this Jesus honours Cuban culture by holding an imaginary cigar in his right hand and a mojito in his left.

Inevitably, as a Bond fan, this immediately made me think of Pierce Brosnan’s distinctive pronunciation of “mojito”. In the scene where he orders the quintessentially Cuban cocktail he’s also smoking a cigar. Bond’s ambivalence about Cuba, depicted earlier in the film by having Brosnan warily wander back alleys while ignoring the charms of a senorita, appears to have evaporated. He may only be a tourist searching for a terrorist but he has started to assimilate into the local culture.

Cuba is, of course, more than mojitos and cigars. For a start, there is also the daiquiri! Joking aside, the daiquiri is a vastly superior cocktail. The drink is named for a town on the southeastern tip of Cuba and dates back to at least 1898 when it was allegedly invented by an American mining engineer (like most cocktail stories, this is probably apocryphal).

And while we’re still stuck on cocktails, it’s mystery to me why the world favours mojitos over negrons, which switches the mojito’s mint for basil and the sugar for honey to much more satisfying effect. I have never seen it on a menu in the UK but perhaps it will catch on one day. The negron was a cocktail hitherto unknown to me until we were introduced to it by a Cuban couple who adopted us for the morning and took us to the places tourists don’t usually traverse.

“Never say 'no' to adventures. Always say 'yes,' otherwise you'll lead a very dull life.”

There were several times during our time in Cuba that I had Fleming’s famous dictum pop into my head. I’d be lying if I said there weren’t a couple of occasions where we weren’t a little fearful, mostly because of Cuba’s reputation. Saying ‘Yes’ to strangers with who you don’t share a language (so that would be ‘Si’ then) is something we are taught from an early age not to do and it’s difficult to fight that programming. And taking a stroll around the backstreets of Central Havana before dawn because we were jetlagged on our first morning was perhaps not the best way to get to grips with a city and country we had never been to. And, as I’ve said before, it’s not as if we blended in. While my husband could just about pass for Cuban with his Castro-like beard (careful, Fleming says they attract radiation!), I didn’t stand a chance. But nothing happened to us, at least nothing bad. For a country with a history of harbouring criminals, there is next to no violent crime. The real Cuba was very different from the place depicted in the films and books I’ve been consuming since childhood. One cliche that was true was how warm Cubans themselves were. Even those who had no pecuniary interest in us were helpful and welcoming.

After a week, we had our bearings geographically and otherwise (it had even become second nature to use three currencies simultaneously). But I still felt we had barely scratched the surface of Havana, let alone the country as a whole. A “hotbed of intrigue” indeed - and one we are very much looking forward to returning to.

To avoid boring readers to tears, I have purposely avoided giving too much detail about the specifics of our trip (hotels, flights, etc). But if you are planning to visit Cuba yourself you might want to listen to this podcast, which we recorded on our hotel balcony on our last day in Havana:

References and bibliography

Before Night Falls (2000) Film. Directed by Julian Schnabel. Distributed by Fine Line Features.

Benson, R (2002) Die Another Day London: Hodder and Stoughton

Benson, R (2023) Personal correspondence, January 2023

Black, J (2017) The World of James Bond: The Lives and Times of 007 Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield

CBC (1964) ‘Ian Fleming: a 1964 interview with the brain behind Bond’ CBC TV Originally aired as part of the Explorations series, 17th August 1964. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1856624190

Chapman, J (2022) Dr. No: The First James Bond Film New York: Wallflower Press

Churchill, W (1930). My Early Life London: Thornton Butterworth

Fleming, I (1963) ‘If I were Prime Minister’ The Spectator, 9th October 1959. Available at: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/if-i-were-prime-minister-by-ian-fleming/

Griswold, J (2006) Ian Fleming’s James Bond: Annotations and Chronologies for Ian Fleming’s James Bond Stories Milton Keynes: Author House

Lycett, A (1995) Ian Fleming: The Man Behind James Bond Atlanta: Turner

Lycett, A (2023) Personal correspondence, January 2023

Playboy (1964) ‘Playboy Interview: Ian Fleming’ Playboy December 1964

Rainsford, S (2018) Our Woman In Havana: Reporting Castro’s Cuba London: Oneworld Publications

Robertson, B (2022) Billy’s Bond Art Book. Self published. [Thank you Billy for the high-res scan of ‘Welcome to Cuba’]

Sainsbury, B and Yanagihara, W (2021) Cuba London: Lonely Planet

Smith, L (2018) ‘Inside Cuba's LGBT revolution: How the island's attitudes to sexuality and gender were transformed’ The Independent, 4th January 2018 Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/cuba-lgbt-revolution-gay-lesbian-transgender-rights-havana-raul-castro-a8122591.html

Stafford, D (2013) Churchill & Secret Service London: Thistle Publishing

Strawberry y Chocolate (1993) Film. Directed by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Juan Carlos Tabío. Distributed by Miramax