Queer re-view: Thunderball

SPECTRE may have stolen two nuclear bombs but stealing their thunder (and the audience’s attention) is Bond being roughly manhandled (and womanhandled) up and down the gender spectrum. Gender is more fluid than ever in this most aquatic of adventures and the 'fairer sex', sick of having less, are giving at least as good as they get.

If this is your first time reading a re-view on LicenceToQueer.com I recommend you read this first.

This article is also available as a podcast, wherever you get podcasts.

‘Inspired by Thunderball’ by Herring & Haggis

The names’s Bond… Flaming Bond

Bond: You swim like a man.

Domino: So do you.

Bond: I’ve had more practice.

He's tall and he's dark

And like the shark, he looks for trouble.

Lyric from Thunderball’s original title song Mr Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, written by john Barry and Leslie Bricusse

Bond: I hope we didn’t frighten the fish.

Bond to Domino, post-coitus

Of all the fantastical things that happen in Thunderball (and there are a lot of them), the one that strains credulity the most is Bond and Domino having sex under water.

By some margin, this tops Bond’s escape from a chateau via jetpack and Largo’s attempted escape via yacht-turned-hydrofoil. The sub-marine sex scene tips the film over into science-fiction.

The harsh reality for those determined to live their Thunderball fantasy is that underwater sex is just not practical, or indeed even possible. I’ve always maintained that Licence to Queer is educational and I’ve done the research so you don’t have to…

A 2019 Cosmopolitan article, snappily titled ‘Your Guide to (Successfully) Having Underwater Sex’, sums up the perils succinctly:

“It's dry (even though you're literally soaking wet), it's slippery, and you low-key may or may not feel like you're getting waterboarded half the time.”

They elaborate:

“Depending on the body of water you’re in, such as the ocean, a lake, or a chlorinated or ozonated swimming pool, you may also run the risk of irritating your vulva and vaginal walls and developing a rash.”

I mean, when you put it like that, it hardly seems worth the effort does it?

Strangely, there are quite a few articles on this topic - in magazines aimed at all genders - from around the same time period. Was this a thing in the late twenty-tens? Did people suddenly start thinking having sex in water was worth trying? Was Guillermo del Toro’s 2017 multi award-winning romantic fantasy The Shape of Water really that influential? [As an aside, when I saw this film in the cinema, a couple on the row behind me did spend the entire screening having penetrative sex, so perhaps my hypothesis is not that outlandish. To their credit, the aquatically-aroused couple did do a commendably good job at keeping their noise level within tolerable limits. For this reason, I didn’t feel compelled to report them to the cinema’s management during or after the screening.]

The articles from the late twenty-tens reach this consensus: water-based sex is just not worth the hassle and it’s possibly even fatal. According to the experts interviewed for these pieces, sex in a lake is the deadliest (all that bird feculence), the shower is the safest (but still unpleasant) and the ocean is somewhere in the middle, along with swimming pools. The latter’s mix of human urine and chlorine isn’t the healthiest environment for sex and the former means contending with saltwater going into places it probably shouldn’t. Choose your poison!

No article (peer-reviewed or otherwise) that I have been able to lay my hands on gives practical advice on how to cope with the additional complication Bond and Domino face in Thunderball: how to copulate while actually under the water, requiring them to strap on ruddy massive oxygen tanks and breathing apparatus. A 2015 piece about Thunderball in Gentleman’s Quarterly understates the difficulty of getting amorous while wearing an aqualung, merely labelling it “logistically impressive”.

The only sensible conclusion we can therefore reach is the following: Bond and Domino are, in actual fact, fish.

Look up! The film endorses this reading, with the oxygen bubbles emerging from both of them as they submerge further behind a tastefully located rock.

Okay, I’m being too literal, I’ll grant you. What I really mean is that Bond and Domino are presented as being so comfortable in this underwater environment - ordinarily quite hostile to air-breathing humans - that they may as well be fish. Bear with me and you’ll see what I mean…

Considering the fundamental differences between fish and humans, it’s funny how we use fish metaphors all the time to describe what we’re doing. Dozens of fish metaphors have slipped into the currents of our everyday speech. There are some great examples in Thunderball.

Largo tells Bond every man has his passion, and that his own is fishing. He follows that up by metaphorically fishing, asking Bond questions about himself. Largo is fishing for information.

Bond calls Largo’s henchman, Quist (played by stuntman Bill Cummings), “the little fish I throw back into the sea”, before throwing him out of his hotel room and sending him back to Largo. With delicious irony, in his next scene, Quist is thrown into a swimming pool and eaten by sharks: a little fish finding out what happens when you meet bigger fish.

Most of the fishy phrases that we use every day are what we call ‘dead metaphors’; they’re as lacking in figurative life as poor old Quist is lacking in literal life because we say them without even noticing they are metaphors. We’re as oblivious as a fish in water.

Pierre Bourdieu was a big fan of a fish metaphor. The French social philosopher used one to explain how outsiders and insiders experience the world differently. Someone who is a product of the social world that surrounds them feels like a fish, blithely swimming along without noticing the water. In these situations, we take the world for granted. It’s only when we enter environments where we are different to the people in that environment that we feel less fish-like. We no longer fit in. Consequently, we notice the water, and we can feel it weighing down on us.

There are times in the Bond stories where he does feel - and sometimes looks - like a fish out of water, especially in the films which immediately follow Thunderball. In You Only Live Twice he’s very obviously a gaijin (foreigner) in Japan, to the point where he radically changes his appearance in an attempt to fit in. Although he dons a kilt in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service to convince as Sir Hilary Bray, his out-of-place bedroom antics are almost his undoing. Bond stands out like a sore thumb in his white tuxedo amidst the scuzzy casinos of Diamonds Are Forever. And who can forget Live and Let Die, where his ‘white face in Harlem’ disguise almost costs him his dignity, as well as his life.

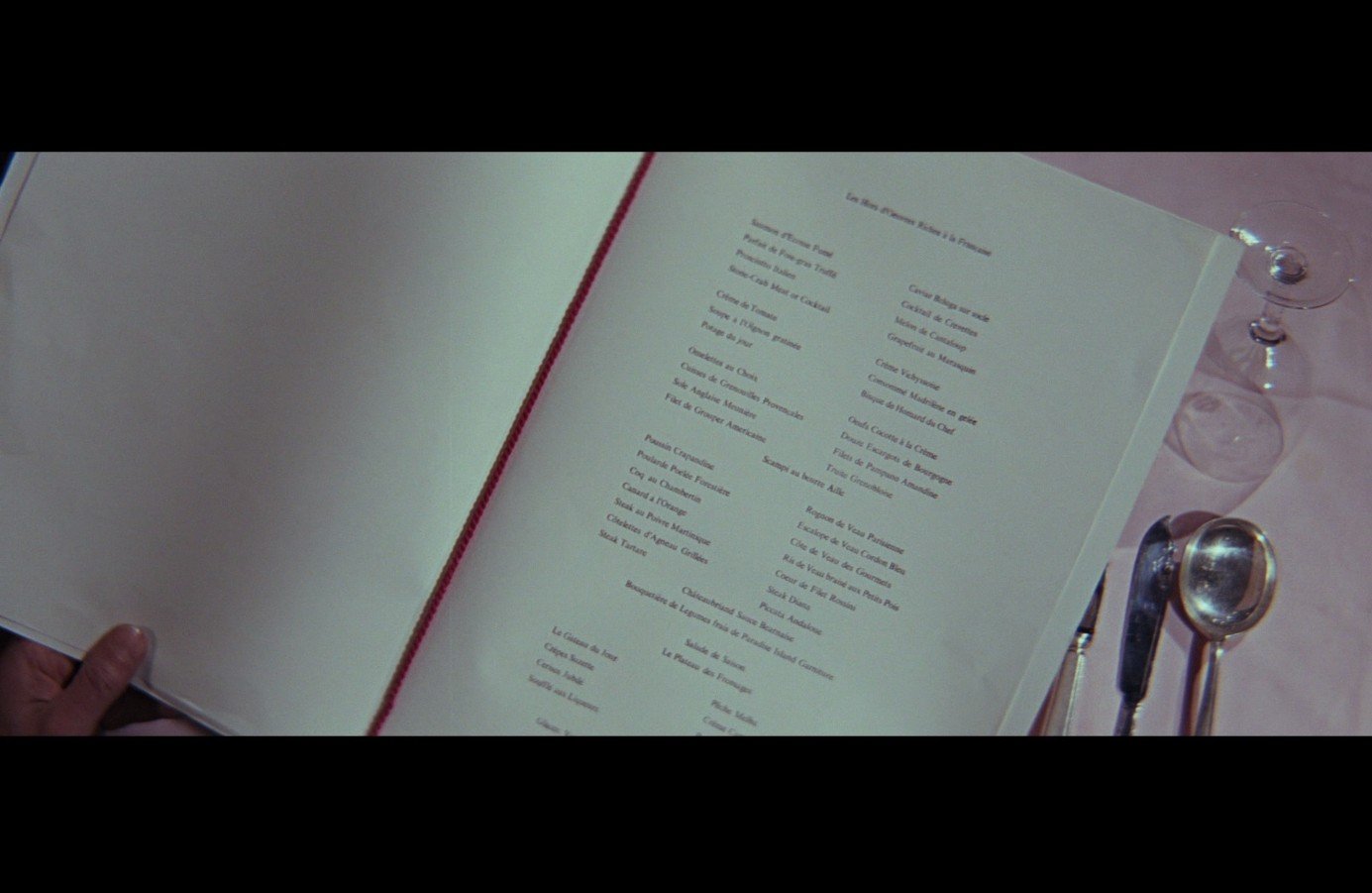

But in Thunderball, he does an exceptionally good job of fitting in. Despite being only a moderately-salaried civil servant, Bond swims through superrich Nassau society as if he was born to it, seemingly at home among the millionaires, washing down Beluga caviar with Dom Perignon ‘55 at harbourside restaurants. To put this in perspective, in the novel of Thunderball, Bond specifically orders £50 of Beluga, which would have been nearly a fortnight’s wages (we’re told Bond earns £1,500 per annum in Fleming’s Moonraker). Either 007 is dipping into his savings from gambling or he’s putting in expense returns which are making M’s eyes water.

Whatever Bond lacks in financial capital he makes up for in Cultural Capital, another term originating with Pierre Bourdieu. It’s an often misunderstood concept, far too narrowly defined as the ‘essential knowledge’ required to be considered ‘educated’. Bourdieu intended it to also include things like how you talk, how you walk, how you dress and how you think. The more Cultural Capital you have - especially the kind associated with the rich and powerful - the more power you have the potential to access yourself, should you want it. People who are not born into wealth usually have to consciously acquire this kind of knowledge in order to fit in. Someone who went to Eton might pick it up without realising. Fleming’s Bond was thrown out of Eton prematurely but he finished his education at another independent school: Fettes. The obituary Fleming gives Bond in You Only Live Twice and the Young Bond books written by Charlie Higson and Steve Cole make it clear that Bond was often made to feel like an outsider in these environments. Even so, would have inevitably picked up knowledge and behaviours which would enable him, as an adult, to slip seamlessly into upper class circles when required. It’s perhaps best summed up by the famous exchange in the film of From Russia With Love: when Bond tells Red Grant he should have realised something was amiss when he ordered red wine with fish, Grant observes “You may know the right wines but you’re the one on your knees.” It’s Grant’s lack of Cultural Capital that flagged him up as suspect, albeit too late for Bond to do much about it.

Although not wealthy, Bond is very much a product of the dominant culture in most other regards: he is white, male and presumably - although never explicitly stated - straight. He fits in particularly well in the Bahamas because it’s a British territory (it gained independence from Britain in 1973, although remains a member of the Commonwealth today). As a British, straight (?), white man, we would expect Bond to cut through life with relative ease. Never mind that there’s a ticking clock courtesy of SPECTRE and Bond is urgently trying to locate stolen nuclear weapons. Thunderball shows Bond in his element; a fish in water.

For me, this is demonstrated most clearly by Bond’s prowess at traditionally ‘masculine’ activities, like shooting things. Whether it’s obliterating a clay pigeon or perfectly skewering a villain with a harpoon, he does these things while barely glancing at his targets. Thunderball’s Bond really is the unchallenged master of the potentially deadly pastime.

Unchallenged by the men at least.

Damoiselles and danger

The only serious challenge to Bond’s privileged status comes from the Girls and, for me, this is where the real drama of the film lies. Personally, I find the plot machinations about stolen nuclear weapons something of a bore. What hooks me into Thunderball is Bond’s interactions with a succession of women who threaten his masculine pre-eminence.

We’ll give the Girls themselves their proper due soon (in their own section, below), but Thunderball takes to the next level the Bond tradition - established in Fleming - of our hero being drawn to women who have manly attributes.

Villainous diva Fiona Volpe rivals Bond not just with a shotgun, but also behind the steering wheel and in bed. Even local liaison Paula, who is this film’s sacrificial lamb, doesn’t go without a fight. And Domino, Bond remarks, swims like a man. (In Fleming’s novel, she also drives like one; always a sure-fire way of signalling to the reader that Bond is about to be smitten with a woman.)

Who even knows how swimming ‘like a man’ differs to swimming ‘like a woman’? Bond doesn’t specify and Domino doesn’t seek elaboration. It’s not the only time Bond verbally polices gender in Thunderball: invited to Palmyra, Bond needles Largo by telling him the gun he’s been handed “Looks more fitting for a woman”. Perhaps he’s self-conscious about such things ever since the armourer, in Dr. No, told him that his beloved Beretta was suited to being carried in a lady’s handbag.

Upon being told she swims like a man, Domino responds - without irony - that Bond does as well. He comes back with the comment “I’ve had more practice”. Perhaps it’s just one of Bond’s customary quips, but it does draw our attention to how much the Bond film series has always been alert to gender being a performance; something that needs to be practised rather than something which is primarily innate. Think right back to the choreographed ‘dance’ across the chemin-de-fer table in Dr. No, every part of Eunice Gayson’s and Sean Connery’s performances carefully curated to signify gendered differences, but also similarities.

To JB or not to JB?

Gender is a spectrum and the enduring success of the Bond character is, in no insignificant part, down to him never being at one extreme end or the other. However, some versions of Bond are more ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ than others.

It’s apt that Thunderball opens on a coffin with the initials ‘JB’ before panning upwards to the JB we’ve been expecting. In those few seconds after seeing the ‘JB’ on the coffin and seeing Connery we’re invited to question: is there more than one James Bond?

Of course there is more than one James Bond, but I don’t mean in a tiresome Codename Theory way.

For those blissfully unaware of the ‘Codename Theory’ (I envy you), this is a painfully awkward attempt to force some kind of continuity onto the series, explaining the change of actor by maintaining that ‘James Bond’ is an alias passed from one Double-O agent to another, the way a Double-O number is passed to another agent when the previous incumbent retires or, more commonly, expires.

The Codename Theory needs to get in the bin not just because it goes too far in explaining an actor merely reaching the end of their contract, but also because it doesn’t go far enough. Not only could we see each Bond actor as a different version of Bond, but also each Bond in each Bond story as a different version of Bond.

As Alan J. Porter has pointed out in The James Bond Lexicon, there are several dozen canonical James Bonds, that is, those which have been officially licensed. And who knows how many hundreds of ‘unofficial’ Bonds there are out there.

The Eon Bond is customarily considered to be one Bond, or possibly two if you take Daniel Craig’s as being a reset of the character, establishing a new continuity. But this is an oversimplification: in actuality, there are as many Eon Bonds as there are Eon Bond films.

Each Bond film is the product of the people who made it and the environment it was made in. But the people and environment change over time so that means the character changes too. While the character may be recognisably ‘the same’ from story to story, especially if the actor in the role hasn’t changed, the characterisation of Bond shifts from story to story. That means we can legitimately speak of ‘Dr. No’s Bond’ and ‘You Only Live Twice’s Bond’ being different, just as we talk of ‘Connery’s Bond’ and ‘Moore’s Bond’ being different.

When there is a change of actor, the shifts in the Bond character are generally more noticeable, but they can be almost as visible when there is a change of personnel behind the camera too. Thunderball marks one of those times.

The spectrum of defeat

Thunderball’s Bond is not entirely without what we might call ‘typical feminine qualities’. But I find it fascinating that earlier versions of the film had substantially more of these. They just didn’t make it off the page or out of the cutting room.

The finished film we got is revealing of an effort on the filmmakers’ part to push the characterisation of Bond several notches towards the more masculine end of the spectrum, certainly compared with the Bond of the preceding film, Goldfinger. On the commentary for the DVD and Blu Ray editions of Thunderball, co-writer John Hopkins relates how he and the other writers were conscious of needing to make Bond a more active participant in this story after 007 spent much of Goldfinger a prisoner of the villain, passively watching events unfold. The character with the most narrative agency in Goldfinger is a queer woman, Pussy Galore. She is ultimately responsible for the successful outcome of the mission after being, er, influenced, by Bond. (Also a special mention to the uncelebrated nuclear bomb expert arriving in the nick of time before Bond pulls the wrong wire.)

Thunderball is, to an extent, a reaction against Goldfinger in its presentation of gender and the different roles men and women are expected to play. Some of this is quite subtle. When you try to pin down gender differences, it can be quite difficult. Sometimes it simply comes down to a mannerism, a pronunciation, an item of clothing. Other times it is less subtle.

He’s suave and he’s not all that smooth

Let’s start with the obvious: Thunderball’s James Bond is very very hairy. Hirsuteness was, and remains, a key social signifier of maleness. Courtesy of the semi-tropical climate of this story, we get a lot of shots of Connery wearing next to nothing, allowing us to appreciate quite how unshorn Sean is. It may be useful - for academic reasons, of course - to compare Bond walking out of the ocean here to Daniel Craig’s Bond, waxed to within an inch of his life, walking out of the ocean in Casino Royale… Okay, I’m not entirely sure of the point I’m trying to make here if I’m honest. Something really clever-sounding about the paradigm shift in male beauty standards over four decades perhaps? But I’m confident it wouldn’t be a waste of anyone’s time to rewatch these scenes a few times. You know, because… research.

While you’re doing your (ahem) research, you might also keep your eyes peeled for other aspects of Connery’s maleness on ample display. Although, to be fair, they’re pretty hard to miss. A very short in-seam on Bond’s swimming shorts was definitely not a Daniel Craig-era innovation.

What’s more (yes, there’s more!) Thunderball wastes no opportunity to make us think about - even when we can’t see them - Bond’s ‘male’ bits.

The whole Shrublands sequence is framed as an attack on Bond’s male virility. The real enemy is not Count Lippe but Bond’s waning libido.

On arrival, Pat Fearing asks Bond about his “funny-looking bruise”. He tells her it was inflicted by a “widow”, rather than using the male-equivalent ‘widower’. We recall Jacques Bouvar attacking Bond in the pre-titles sequence while disguised as a woman but Pat doesn’t know this and is therefore surprised when Bond follows it up with “He didn’t like me at all”. We’re also reminded that Bouvar attacked Bond with a poker, which has been used as a synonym for penis since at least 1793 and continues to be used, particularly in queer contexts, today (see Jonathon Green’s fascinating dictionary of slang for more on this). Perhaps the most famous use of a poker as penis substitute is the killing of 14th Century English monarch Edward II. It’s probably apocryphal that he was murdered by having a red hot poker inserted into his anus but that hasn’t stopped the story taking hold. The probably-queer king was not short of people who despised him for a multitude of reasons, but homophobia has surely played a part in so many believing without question - and perhaps with a rather horrifying sense of schadenfreude - that he died being buggered to death with a scalding phallus of iron.

Even if you aren’t consciously aware of the poker in Thunderball being a penis substitute, there’s no denying that Bond has been on the receiving end of a somewhat sadistic assault from another man - one who was feminised through their clothing at the time. Yes, Bond did win the day by strangling Bouvar with his own poker (the symbolism is surely not lost on anyone by this point?) but he is recovering from the experience of almost being put in the ‘womanly’ position.

Adding insult to injury, Moneypenny lampoons Bond’s libidinously-diminished situation. Down the telephone she refuses to help Bond with his investigation into Count Lippe’s tattoo because he’s off-duty. When Bond threatens to put her across his knee, Moneypenny sarcastically reminds him that he’s on a strict diet of healthy foods and would therefore find such an assertively masculine performance an uphill battle: yoghurt and lemon juice are hardly famed for their fortifying or aphrodisiac properties.

Bond’s sexual pestering of Pat Fearing is an attempt to reassert his masculine prowess, which she thwarts by strapping him to a traction table. He childishly resists, straddling the machine and asking “Where’s the kickstarter?”. After Lippe’s attempt to kill him on “the rack” fails, Bond remarks “I must be six inches taller”. If we weren’t thinking about Bond’s penis already, we are now. In real life he would be in agony of course. But in this fantasy version of reality there’s a sense that being vigorously rubbed up and down on a traction machine - a simulacrum for man-on-top sexual intercourse - has reinvigorated Bond’s libido. In the shooting script, the line is just as laden with innuendo, although perhaps a bit less assertively stated: “I feel like I’ve grown about six inches”.

These are so many differences like this between the different versions of Thunderball: the script, the film as shot and the edit which eventually made it to our screens. Taken on their own, they may not add up to much. All films are shaped during the production process. But when considered together, I believe they constitute an attempt on the filmmakers’ part to give Bond a (manly) shove towards the traditionally masculine end of the gender spectrum.

His days of asking are all gone?

The different iterations of one of Thunderball’s most contentious scenes illustrates how Bond’s gender identity was being reshaped throughout the production process.

The end of the traction table sequence has Bond coercing Fearing into having sex in the Turkish Bath. The scene in the finished film is an increasingly uncomfortable watch as time goes on. And while the shooting script doesn’t absolve Bond’s actions, the scene has a very different feel.

For a start, everything is less obviously focused around Bond’s penis. Fearing’s line “It might even shrink you back to size” is not in the shooting script and appears to have been improvised during the shooting. Bond in the script is also more grateful to Fearing for coming back and saving his life and they have some light-hearted banter about Bond buying her a gift as a reward. The scene continues for a lot longer than it does in the finished film, with a hard cut to Bond and Fearing already inside the steam room. It’s not clear who led who there. In the finished film, Bond moves towards Fearing and she is compelled, physically, to back into the steam room. In the shooting script, the only thing we see clearly through the steam are “a woman’s bare feet as she stands on her tiptoes stretching upwards. A few inches away are the man’s feet and legs”. This makes it clear that Fearing initiates the first bodily contact as she tiptoes up to kiss Bond on the lips. The scene continues with some detailed directions that wouldn’t be out of place in an Austin Powers movie:

“CAMERA PANS UPWARDS, past a thicker bank of steam which conveniently covers up everything until out of the mists emerge bare arms and shoulders… The steam reaches higher and higher making it even more difficult to see anything at all. This is probably just as well.”

But the most crucial difference is that Fearing is controlling what happens inside the steam room. She is “laughing” and she gets the final say, quipping that “No, you’re wrong…. This is not what I meant by the full treatment”.

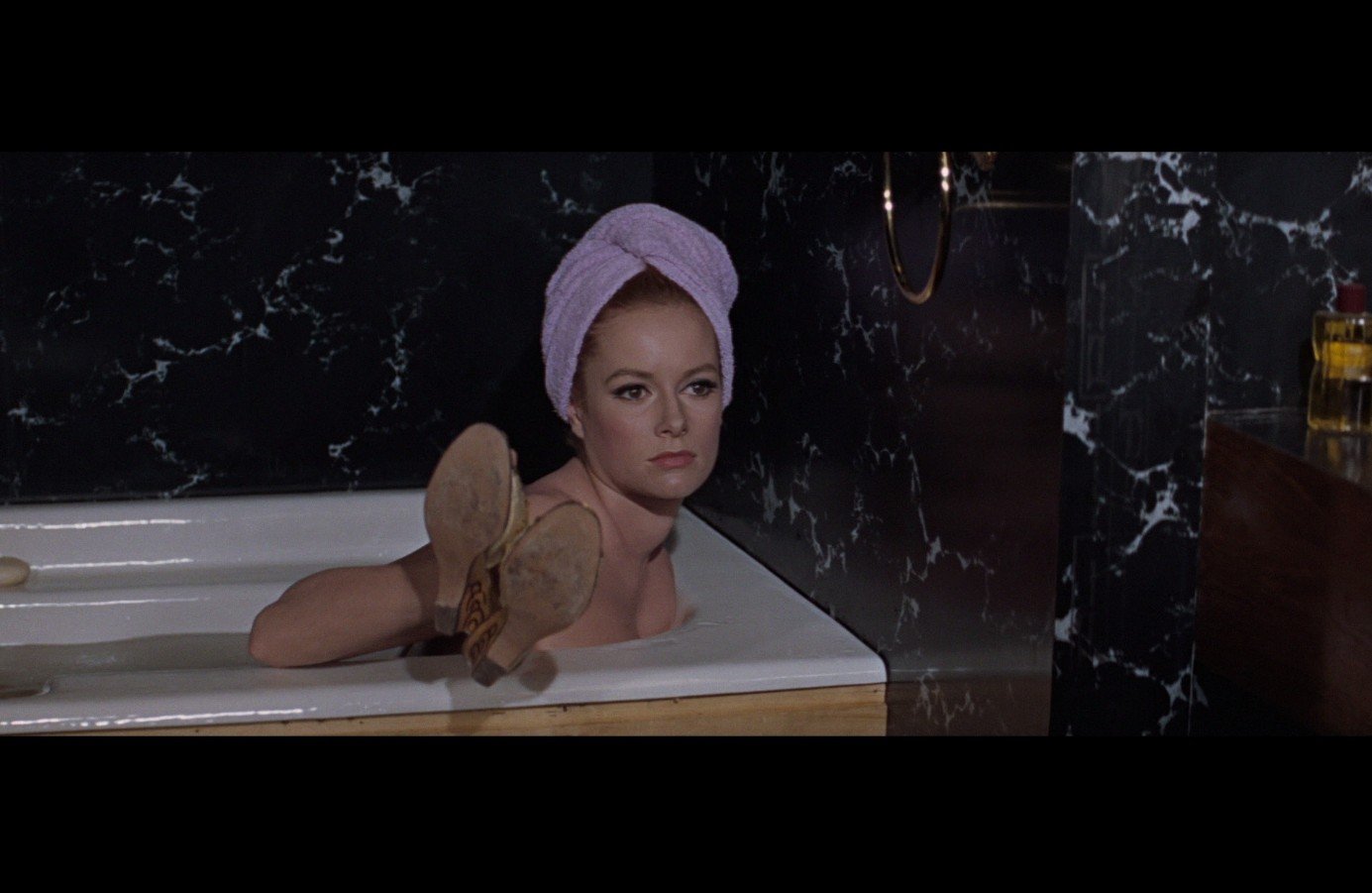

This is a call back to an earlier scene which was filmed but deleted. Originally, in Bond’s and Fearing’s first meeting she is “vigorously” massaging him, her “expert manipulations” causing Bond to emit “a series of involuntary grunts”. After giving him a good pummeling, she eases off and puts on a mink glove. Production photographs exist of this part of the scene at least. Was the scene deleted for pacing reasons? Or perhaps because it was too similar to the way we meet Bond in Goldfinger, being massaged poolside by Dink? (Dink not mink). Or maybe Bond being on the receiving end of a massage with a mink glove might have feminised him too much?

I suppose it comes down to how much we should read into a mink glove?

MinkGlove.com, an online shop specialising in mink gloves (what else!) plays up the Thunderball association so sell their wares:

“Give your partner the Mink Glove treatment with James Bond's sexiest weapon ever! Wielding only a soft & sensuous mink glove, Bond seduces a prim and proper but very bodacious blond into total submission in the movie Thunderball. Even in real life, the actress Molly Peters still relishes the memory of her mink massage. "It was totally mesmerizing and almost sent me into a trance!" as she sighs in satisfaction over the sensual mink glove fur massage given by Sean Connery as James Bond.”

Leaving aside that this is a sales pitch (and that actress Molly Peters passed away in 2017), there are some highly questionable language choices here, not least “total submission”, which hardly represents even what happens in the finished film. And we know from the shooting script that, if the mink glove was intended to be a ‘sexy weapon’ it belonged to Patricia Fearing, not James Bond. She was the one who started off the seducing.

Dr Lisa Funnell has argued that Fearing is aptly named because she is fearful of Bond’s “libidinal masculinity”. While an entirely valid reading of the finished film, had the scene of Bond’s and Fearing’s first meeting been kept in the film (complete with Fearing’s mink massage of Bond) and the steam room encounter been shot as scripted, there would have been less of a power imbalance. Perhaps Bond might have been a bit afraid of her too?

He will break any heart without regret?

There are many, many more differences between the finished film and the shooting script and in almost every instance the scripted version presents us with a more stereotypically ‘feminine’ Bond. I particularly enjoy some of the dialogue differences. In the film, when Bond narrowly avoids being eaten by sharks in Largo’s pool, a dubbed over line has Connery telling the shark “Sorry old chap, better luck next time.” The shooting script has “Sorry, loves - you’ll have to order something else - I’m off!”

If we return to the scene on the beach, after Bond and Domino have frightened the fish, we find this was also drastically different in the shooting script. It’s about half the length in the completed film, the cutaways to Vargas covering for the missing material which has Bond apologising to Domino for having sex with her for the sake of the mission. Domino tells Bond she hates him. His response is faltering, regretful and sincere: “I came to tell you that - and then - seeing you - knowing it was now - or perhaps never - yes - I made love to you… I didn’t want to tell you, Domino. I didn’t want to hurt you.” In the screenplay, he “gently, takes hold of one of her hands” whereas in the film he roughly grabs her arm and shouts at her: “Look, Largo had your brother murdered!”

At this point, Domino might even be regretting having told Bond he was “not like Largo”. Bond himself drew the comparison and it’s one we’re invited to make throughout the film, certainly after we’ve heard the finished film’s title song.

Of all the changes made during the production process which ‘masculinised’ the film, the change of title song is the most significant. The original song which Barry used for the basis of the film’s score, Mr Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, was seen by the composer as a way of to “redefine Bond”. Leslie Bricusse’s lyrics - written while the film was still shooting - capture the character’s masculine and feminine qualities.

“He's suave and he's smooth

And he can sooth you like vanilla /

But remember that

The gentleman's a killer.”

According to John Burlingame, Bricusse didn’t watch any footage or read the script so went off Barry’s melody and what he knew already of the Bond character. When the song was jettisoned from the film very late in post-production, John Barry asked Don Black to write a lyric for a new hastily-written melody. Compared with the lyrics to Mr Kiss Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Black’s lyrics to Thunderball are hyperbolically macho:

He always runs while others walk.

He acts while other men just talk.

They call him the winner who takes all.

And he strikes like Thunderball.

He knows the meaning of success.

His needs are more so he gives less.

He looks at this world and wants it all.

Then he strikes like Thunderball.

Any woman he wants, he'll get.

He will break any heart without regret

His days of asking are all gone;

His fight goes on, and on, and on.

But he thinks that the fight is worth it all;

So he strikes like Thunderball…

Some contemporary reviewers - and more recent commentators - have argued that the lyrics to Thunderball are about Largo, particularly because of the line “He looks at this world and wants it all”. Singer Tom Jones said the song was about neither Bond nor Largo, but about “a fictitious character… not really in the film”. Black himself is unequivocal: it’s about Bond. He felt it was “a summation of that lifestyle”.

While the title song was, by all accounts, switched at the last minute for marketing reasons, it’s possible that the producers also felt the need to have a song opening the film which mirrored the more masculine Bond who was emerging from the cutting room.

He knows the meaning of success?

As easy-going as Bond appears in Thunderball, the man bringing him to life on screen was feeling increasingly unable to swim, run or even walk through life as he liked. Weighed down by the never-ending press attention, Connery only gave one major interview. It appeared as a Playboy exclusive in November 1965, a month before the film’s release. The interviewer observed that Connery was “in many ways the antithesis of his urbane, Eton-bred screen self”, someone who “prefers beer to brut blanc de blanc”.

By this point, Connery was all too aware of how much of a masculine fantasy Bond had become. He remarked that a big part of the appeal of the Bond character was because he is someone “who cuts right through” the drabness of post-War life, “like a very hot knife through butter”, citing Bond’s “clothing and his cars and his wine and his women” as the “survival kit” men could use to escape humdrum existences.

To the relief of all readers - including perhaps queer ones - who were starting to feel like they were falling short of living the Bond fantasy in its entirety, Connery told Playboy that:

“I've never been a womanizer, as Fleming called Bond. I still like the company of women ... but then, I like the company of men, too. They offer a different sort of fun, of course.”

Even more relatably, Connery - who was perhaps eager to distance his real self from his screen self - confessed to Playboy that he had “a fear of sharks and barracudas, and I have no hesitation at all in admitting it. It's not that I'm allergic to them... it's just plain fear”. He also said that, while he was “fond of swimming… all this stuff underwater with bottles of oxygen strapped to one’s back in Thunderball doesn’t thrill me to bits”.

So no under water sex for him then. Way to torpedo that fantasy once and for all Sean!

Friends of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

Individualism and self-reliance are typically seen as masculine traits but Thunderball’s Bond is already at risk of tipping over into a masculine caricature so it’s a good thing that he’s made to be more reliant on the support of others than he is in any of the three previous films. These others include regulars Felix Leiter and Q (in the field for the first time) and local contacts Paula and Pinder. It’s an early example of the ‘found family’ or ‘chosen family’ we typically associate with some of the Pierce Brosnan films and definitely the latter half of the Daniel Craig era. These less traditional conceptions of family inevitably resonate with many queer audiences who may have not have the support of people to who they are related legally or by blood.

Felix Leiter is once again feminised when placed alongside Bond, a tradition dating back to Fleming’s Casino Royale where Felix marvelled at the size and strength of Bond’s Martini. The Central Intelligence Agency operative always has less narrative agency than Bond and Thunderball is no exception. He’s the classic ‘helper’, who aids the hero on their mission, swooping in to rescue Bond when he’s left trapped in a cave by Largo. But when it comes to the final battle, Felix is left behind. In the shooting script Bond tells him to “mind the store”. In the finished film Felix just wishes Bond “Good luck” but not until he’s helped Bond strap on his waterjet from Q Branch. When Bond feels self-conscious about strapping on something the size of the “kitchen sink”, Felix gives his ego a stroke: “On you, everything looks good”. We all need a Felix in our lives.

Paula Caplan is a character of a very rare type in Bond; a highly capable female field agent who may want to sleep with 007, but only if the mood takes her. But sex is all there is and she’s not going to lose sleep about it. In modern parlance, Bond might be her ‘friend with benefits’. She’s certainly not going to be mooning over him when he inevitably has to sleep his way across Nassau for king and country.

When Bond asks Paula to “Tell London I’ve made contact with the girl” she responds, suggestively, “It’s not what I’d call contact”. They share a lovely moment on the boat where they are both complicit in Bond having to use his body to further the mission.

Even though Bond leaves Paula to go off on Domino’s boat, she doesn’t appear fazed by his desertion. However, in the shooting script, Paula was intended to look on Domino’s departing boat - with Bond aboard - with “mingled feminine and professional reactions”, hinting that she might be jealous? This isn’t how the character reads in the finished scene. Actress Martine Beswicke herself concurred with my reading of her character, telling me: “You are absolutely right about Paula. Yes she would have probably enjoyed a romp with Bond but jealousy was not her thing, even if she might make a dig at him for his sexual antics.”

When Volpe enters Bond’s hotel room, Paula is more puzzled than jealous, refusing to rise to Volpe’s bait when she says “He has a date with me too”. When Paula is kidnapped by Volpe and her men she puts up a struggle, which is slightly truncated in the finished film. The shooting script reveals that the scene had Paula forcefully refusing to give Volpe any information about the photographs of the Disco Volante.

Q scenes are typically some of the most light-hearted in the Bond adventures so how are we supposed to take a joke rooted in the horror of anal intrusion?

Here Bond is given a homing tablet and asks Q what he should do with it. The pause after “Obviously, you…” allows the audience - and Bond - to draw their own conclusion before Q supplies the answer “…you swallow it.” In the pause we’re supposed to think Bond might be being presented with a suppository. Are we to imagine him shoving it where the sun doesn’t shine when he inevitably needs to be rescued later in the story?

Connery’s line “Now?”, which defuses the awkward tension somewhat, was adlibbed.

Shady characters: Villains

Thunderball is the first Bond film not to feature stuntman Bob Simmons as Bond in the gunbarrel: this time, it’s actually Sean Connery. However, Simmons more than makes up for it by appearing as a villain in “full drag” (his words, from his own book) in the pre-titles fight sequence.

The idea of having Bond fight with a man dressed as a woman appears in the early treatments of Thunderball, prior to the scripting stages. It does not, however, appear in the Ian Fleming novel which was based off the screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham and Ian Fleming. Nor does it appear in Kevin McClory’s 1983 remake of the story as Never Say Never Again. We can safely conclude then, that it was an idea of Richard Maibaum’s, the screenwriter who we can credit - for better or for worse - with bringing some of the most bizarre elements into Bond.

In Maibaum’s original conception, Thunderball opens in Hong Kong, where Bond is on a third floor balcony playing the card game fantan and staring at a girl across the way from him. He receives a message from M - via a Chinese ally - that he either needs to do the job he’s been sent for or come home. It emerges that Bond is there to assassinate Ho Yen who is a “shadowy character, most elusive”. Bond gets up and walks over to the girl who he starts to “romance”. After a while, 007 pulls off her wig, revealing the girl to be a bald-headed Ho Yen. When Ho Yen’s dress is ripped off it reveals “Yen’s muscular male torso”. Having killed Ho Yen, Bond escapes by diving into the swimming pool below him.

Like a lot of Maibaum’s ideas for Bond, it’s both kind of homophobic and kind of cool, exploiting the audience’s discomfort at non-normative practices, such as men wearing women’s clothing. Decades later, we are still yet to see Bond ‘romancing’ a male antagonist and part of me thinks it’s a shame this version didn’t make it to the screen. On the plus side, at least we were saved from the spectacle of Bob Simmons impersonating a Chinese person.

In the finished film of Thunderball, it’s not Bob Simmons under the funeral veil to begin with but actress Rose Alba as Colonel Jacques Bouvar, who it quickly transpires has exploited society’s gender expectations to be able to sneak into his own funeral.

In the shooting script, the name Bouvar does not appear. Both Madame and the Colonel are referred to as Boitier. It would make sense for them to have the same surname. For the Colonel’s ruse of faking his own death to last more than a minute, he would have to have been married to Madame at some point. And she must exist somewhere, hidden out of sight? However, the end credits of the finished film complicate matters for those of us who really enjoy reading too much into things which were probably just film-making mistakes. On the credits, Rose Alba is credited as ‘Madame Boitier’. Why wasn’t it changed to Madame Bouvar? Thunderball’s final stages of production were very rushed, so it probably is just a typo. This wouldn’t be the first time such a mistake happened. On the opening titles of From Russia With Love, Martine Beswicke is credited as Martin, misgendering her in the process. Her name is spelled correctly in Thunderball’s credits (albeit without the ‘e’ which is her real, not stage, name).

If we wanted to make something of the Bouvar/Boitier confusion, we could hypothesise that Colonel and Madame are actually the same person, but with two different names, and two different identities. This still makes the Colonel’s attempt to fake his own death something of a non-starter. Surely Bond would have done a quick background check? But it does also raise the tantalising possibility of Madame Boitier being Colonel Bouvar’s alter ego. Or is it the other way around?

Whether Jacques’ femininity is a performance or actually part of him, he doesn’t ‘pass’ as a woman for long enough for his plan to succeed.

Opening the car door himself rather than wait for a man to do it for him is his undoing. The societal expectation that men open car doors for women (but not the other way around) is one example of what Judith Hall calls ‘benevolent sexism’.

Bond appears to have bought into this… when it suits him. Later on, Bond does not even think of opening the door of Fiona Volpe’s Mustang after she attempts to emasculate him by taking him for a high-speed ride. As for Bouvar and his fateful mistake, should we conclude that he’s just forgotten that he’s supposed to be acting in a ‘lady-like’ fashion?

The detail that Bouvar “opens it herself” is underlined in the shooting script. The script uses female pronouns (she/her) throughout for Bouvar, until he reacts to Bond outing him as male, when the script switches to male, although not consistently. After we’re told Bouvar has pulled back “his knees” to kick Bond in the stomach we’re told that he “jumps to her feet, comes at BOND, knife poised” (my emphases). Only male pronouns are used after the wig comes off “revealing a man’s cropped hair”. In Bond, hairy chests may be male, but hairy heads are female. Even so, the sequence as scripted is more of a slow reveal of Bouvar’s gender.

The finished film goes for more shock value by having Bond punch Bouvar in the face before there’s even a hint that Madame is not who they are claiming to be. It’s a moment spoofed in 1997’s Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery, with Bond-stand in Austin punching someone who is evidently a woman before cutting to them on the floor, a completely different actor, this time one with a five o’clock shadow.

Even in tongue-in-cheek form, such scenes are intended to make audiences briefly uncomfortable. Which of the two boxes - man or woman - should we put this character in? And is it ok for our hero to punch them if they’re one sex but not another?

For his part, Bob Simmons was only made to feel uncomfortable when Terence Young and Sean Connery played a practical joke on him. In his book, Simmons relates how the director and star had moved the make-up station from the chateau where they were filming to the hotel where they were staying. This meant Simmons had to have his costume and make up done in the hotel before walking through the foyer to get to the car taking him to the filming location. He remembers: “I felt a right Charlie and the last glimpse I had of Terence and Sean was as they collapsed in two huge chairs in the foyer, gulping for air in barely controlled hysterics. Some stunt.”

The onscreen stunt Simmons performed in drag was the one he says he enjoyed doing most out of all of those he did in the Bond series: “It was a good scene, well choreographed. I was proud of it”. As for impersonating a woman, Simmons admitted that he was “no Danny la Rue”, a reference to the immensely popular British drag artist, whose offstage name was Daniel Carroll. Simmons may not have been Danny la Rue but he was fully committed to becoming Madame Boitier, even wearing a suspender belt and knickers, although he was adamant he’d put those on himself, rather than seek the assistance of the costume department. Perhaps he was so committed to a full female makeover because the original script called on him to be pretty much stripped off by Bond: very little would have been left to the imagination!

During the scripted fight “BOITIER fights his way out of BOND’s grasp, leaving half the dress in BOND’s hand, exposing the falsies he is wearing”. Yes, you read that correctly: while the script always featured the Colonel attacking Bond with a poker, Bond never got the chance to wield it himself. The fight originally ended with Bond killing the Colonel by strangling him with his own fake breasts. “BOND, still holding the falsies, whips them around BOITIER’S throat, like a garotte… Then he slowly tightens the falsies around his neck and strangles him.”

There are some revealing directions in this part of the screenplay, in every sense of the word. From a gender standpoint, it’s curious that the battle between Bond and the Colonel is described as a cat fight: “They stagger to their feet, clawing at each other”. Bond is being feminised along with Bouvar; perhaps the scriptwriters wanted us to think of Bond’s masculinity being diminished because he fights someone who is more feminine than his usual adversaries.

As a queer person, I have always been a little disquieted by this scene. It’s a brilliantly choreographed fight and one of the most savage, perhaps because of that fear of Bond being feminised? But the savagery makes it feel like the character of Bouvar is being punished for transgressing social norms. Although we are told Bouvar is a double-murderer, we don’t see these crimes. The only ‘crime’ we see Bouvar commiting is wearing feminine clothing. I think this would have been even more apparent in the version as scripted, with such an obvious symbol of femininity used to perform the coup de grace.

Hairy hands

Later in life, Simmons told Bond stunt expert Jon Auty “one thing” he “couldn’t do again” was “be a woman”, mostly because of the inconvenience of having to shave his legs.

So far in Thunderball we’ve dealt with the gender expectations of hairy legs, chests and heads. But what about hands? The shot of Count Lippe’s hairy hands manipulating the lever on Bond’s traction table is the first sign that something is very wrong. In the novel it’s the same:

“In front of his eyes was a hand, a man's hand, reaching softly for the lever of the accelerator. Bond watched it, at first fascinated, and then with dawning horror…”

Hairy hands are most definitely the preserve of the male sex in Thunderball, unless they are women’s hands ‘dragging up’ as men’s hands by wearing mink gloves. The novel of Thunderball, like the original shooting script, has Fearing doing the mink massaging of Bond.

But in the hairy hands stakes, no one comes close to Largo in the novel. And, by the sounds of it, no one would want to!

“An aid to his athletic prowess were his hands. They were almost twice the normal size, even for a man of his stature, and now, as they walked across the chart holding a ruler and a pair of dividers, they looked, extruding from the white sleeves that rested on the white chart, almost like large brown furry animals quite separate from their owner.”

While Largo’s extremely hairy hands in the book are intended to be signifier of “athletic prowess”, they could make some readers think of the myth (origin unknown but several hundred years old) that masturbation gives you hairy palms. Either way, in the film, we are saved the spectacle of having to take seriously a main villain with bizarrely big ferret hands.

A detail we don’t get in the book but which was added for the film is Largo wearing an eye patch. So we’re saved from one mythical symptom of masturbation and presented with another: blindness.

He’s not the first Bond villain with non-normative eyesight: Dr. No begins with three ‘blind’ assassins. Nor is he the last: Casino Royale‘s Gettler is one-eyed and No Time To Die’s Primo sports a gadget-augmented eye-ball before it’s blown up by 007. See the queer re-views of those films for further details but, in a nutshell, the research shows that blindness on screen can make sighted viewers unsettled. Men in particular may feel like they have lost something which makes them powerful, akin to castration.

Largo’s eye patch is a visual representation of something which was more suggested in Fleming’s book: that he’s a spiritual descendant of pirates like Blackbeard. He also has a preference for double-breasted jackets, vaguely resembling naval attire. And let’s not overlook that he spends a lot of his time on a ship populated almost exclusively by men.

Although in the Golden Age of Piracy there were pirates of all genders, many ships were homosocial societies, microcosms of society - but even more male-dominated and free of some of the constrictions of mainstream society. Relationships of the sort that would not be thought of as ‘normal’ by landlubbers flourished. Most modern historians don’t dispute that homosexual acts were common in these floating societies, including among people who would probably not identify now - and certainly not then - as bisexual or gay. But there were also special relationships including an agreement called ‘matelotage’ (French for ‘Seamanship’). Common among European sailors, when you entered a matelotage with a crewmate you pledged to take care of each other: you would share income, inherit their property and protect them in battle. ‘Til death do us part, indeed.

Even the name ‘Disco Volante’ makes Largo’s ship sound to modern ears like a slightly-past-its-prime gay bar, albeit one with a still-functioning smoke machine!

Point made?

Many of the terms we use for queer identities were not coined until well after the Golden Age of Piracy. ‘Asexual’ predates homosexual, heterosexual, lesbian, gay and bisexual, first being written down in the early 1800s. Fleming uses the term in his books but it has yet to appear in the films.

Vargas is never actually called ‘asexual’ but he is coded as such in this dialogue from Largo:

“Of course. Vargas does not drink... does not smoke... does not make love. What do you do, Vargas?”

Fenna Geelhoed, who is demisexual, observes:

“Lumping Vargas’s abstinence from sex in with his abstinence from other human pleasures like alcohol and cigarettes seems to be another way of saying that we can’t really consider him to be alive. That is of course historically the trouble with asexual representation: the negative stereotype that asexual people are somehow inhuman, cold, sick.”

There are several other examples in Bond, particularly Red Grant who is explicitly identified by Fleming in the novel of From Russia, With Love. Geelhoed cites several other Bond characters who are potentially more positive representation, including Melina in For Your Eyes Only and Paloma in No Time To Die.

Given his apparent asexuality, it’s particularly cruel that Vargas is killed with a very phallic harpoon: Bond asserting his male dominance again? Although, given the likelihood of being murdered by penis-like objects in Thunderball, it’s entirely possible that it’s more a matter of probability than design.

Murder on the dancefloor

We have seen how some people - particularly people like Bond, who are white, male and presumed-to-be straight - are typically able to swim through life without feeling the water weighing down on them as much as others feel it. That doesn’t mean if you’re in a more privileged position you are automatically oblivious to how others experience the world.

Straight-identifying white man Pierre Bourdieu was aware of it. And he was amazed by it:

“Throughout my life I have been amazed at… the fact that the order of the world as we know it, with its one-way streets and its no entry signs (both literally and figuratively), its obligations and its penalties, is generally speaking respected. I find it surprising that there are not more transgressions and subversions…”

Understanding why people didn’t challenge social norms which were no good for them was what drove Bourdieu in his work. Why, he asked, do we put up with such ‘madnesses’?

“Male domination is so rooted in our collective unconscious that we no longer even see it. It is so in tune with our expectations that it becomes hard to challenge it.”

I would have loved to have sat down with Bourdieu, should he have been willing, and watch Thunderball with him. Unfortunately, Bourdieu died in 2002, at the age of 71. I have a feeling he would have admired the various challenges the characters of Thunderball mount to male domination.

You can’t think of Thunderball without thinking of Fiona Volpe.

For the purposes of this queer re-view, I have - after much deliberation - categorised Volpe as a villain. She’s not the first character in Bond who has been difficult to pigeonhole. Labels, as ever, can be limiting and the whole point of reading something queerly is to break down traditional barriers and boxes. And if there is a character who resists being caged, it’s Fiona Volpe.

Even if Volpe does end up dead on a dancefloor, she’s one of the elements of the film which lingers longest in our memories. Meeting a sticky end but sticking in our minds more than the men who fall for them is the hallmark of a femme fatale, a character type with a big queer following.

Kirsten Smith cites Mata Hari as the blueprint for 20th Century fictional femme fatales. Mata, whose birth name was Margaretha Zelle, was possibly not even a spy. Yet the Dutch exotic dancer was executed by the French government in 1917 after being convicted using trumped up evidence from British Intelligence. After losing millions of men on the battlefields of the Somme and Verdun due to a series of military blunders, France and Britain needed a scapegoat. Whether she was an actual spy or not was largely immaterial in their minds. Her greater crime was transgressing gender norms. When questioned by the authorities about her sexual activities, she was unapologetically open about her sex life. She had a particular taste for military men, which probably didn’t help her case.

There is fragmentary evidence that Mata enjoyed dressing up in the men’s uniforms and may also have had sex with women. But even without this, Mata’s refusal to feel shameful for that most natural of acts - sex - makes her a queer icon. In 1931, openly bisexual Marlene Dietrich appeared as a character based on Mata Hari in Josef von Sternberg’s film Dishonored. Prior to being shot, she reapplies her lipstick in defiance of the firing squad.

It’s an ending Fiona Volpe might have appreciated, had she had the opportunity to see the bullet coming! Even so, it’s possible to trace a direct lineage from the Mata Hari of the popular imagination to Fiona Volpe meeting a bang bang on the dance floor of the Kiss Kiss Club. Whether Mata was, in actual fact, as fatale as the male authorities claimed her to have been, she was most definitely femme.

Hyperfemininity is, according to Kirsten Smith, “the femme fatale’s greatest weapon because of its allure to the hero”. This was particularly the case in the mid-late 1960s when gender norms were more liminal than they had been in the previous decades. Even so, you can see it in the femme fatales from the classic film noir period, which is often said to have ended with 1958’s Touch of Evil (in which Dietrich also stars). In this classic period of the 1940s and 50s, some directors very knowingly poked fun, antagonising their weak-willed male heroes with ridiculously exaggerated visions of women. Anyone who has seen 1944’s Double Indemnity will find it hard to forget the massive blonde wig worn by Barbara Stanwyck. According to the film’s director Billy Wilder, whose outsider point of view gave all of his films a queer sensibility, it was “obviously phony”.

For viewers who are sexually attracted to women, Fiona Volpe has all of the obvious pleasures - in ample amounts. And the rest of us, she’s an absolute scream.

Her combination of extreme violence with extreme femininity means we find her both sinister and empowering. As we have already seen from the pre-titles fight with a man in drag who we don’t immediately realise is a man, the film continually plays with our expectations around gender. When we see Count Lippe halfheartedly attempt to kill Bond as they both drive away from Shrublands, we expect Bond to dispatch him using the DB5’s box of tricks familiar to us from Goldfinger. However, the unknown rider of a speeding motorcycle obliterates Lippe and his vehicle with a somewhat overpowered rocket. When the rider removes the helmet to reveal flowing red hair, we are expected to be taken aback: a woman?! Thunderball’s co-screenwriter John Hopkins says on the film’s DVD commentary: “I think that’s the first time that a girl took off her helmet and revealed her gender by the length of her hair.”

But there’s so much more to Fiona than hair. So much has been written about other elements of Volpe’s appearance. For instance, Laureen Gibson observes that Volpe challenges the gender binary because her costume and “overly made up appearance” combine to reinforce “feminine pageantry”. Volpe is a female drag queen, highlighting - as Bond does in the film’s dialogue - how much gender is a performance.

For me, it’s always been the bright blue feather boa which is the piece de resistance. The ridiculous size of it is important of course, but so is the colour. There appears to litte rhyme or reason to the colour choices in this film. For the most part, there’s minimal adherence to the convention of pink being associated with femininity and blue with masculinity. The men and women of Thunderball mix and match from scene to scene. Fiona wears a pink blouse at one poin. But it’s vital that she’s in blue for the scene where reveals to Bond who she really is. Publicity images of actress Lucianna Paluzzi suggest a pink feather boa was considered at some point. This would not have been as impactful.

Blue is the rarest colour in nature. In cinema, it’s still used to denote something which is otherworldly or unnatural (for instance, think of all those Marvel macguffins which glow blue). It’s vital that Volpe wears blue when she confronts Bond about his male vanity. She is literally going against nature, as defined by a patriarchal society.

It’s one of the most cited scenes in Thunderball for a reason: it reflexively skewers Bond’s sexism decades before it became fashionable. And yet, the scene in question was intended to be staged very differently.

In the shooting script, Bond unmasks Fiona as a SPECTRE agent while she’s sitting at her dressing table. After Bond brings up that she wears the same ring as Largo, she gains the upper hand by putting a knife to Bond’s throat - a knife concealed in a lipstick. She reaffirms her threat by holding the blade close to Bond’s genitals. Could there be a more obvious threat to Bond’s masculinity?

With the threat of castration-by-lipstick in the finished film absent, Volpe attacks Bond’s masculine dominance while wearing a feather boa in the most ‘masculine’ colour: a woman appropriating masculine dominance while already personifying the most fabulous version of femininity possible.

The dialogue in the script is similar to that of the film but not as punchy:

“All this must be rather a shock. I mean… the girls you’ve made love to in the past…. They’ve only been too glad to do anything for you. But this time…. It’s different. This time, lover - the great - charm - is wasted.”

It’s more of a monologue, with Bond not getting chance to interject. In the finished film, Bond tries to push back: “My dear girl, don't flatter yourself. What I did was for king and country. You don't think it gave me any pleasure, do you?”

The “king and country” line can be read any number of ways. Is this what was hard-wired into Bond during his war service? Is he flustered and falling back on a default phrase? Or is it Bond, feeling threatened by a woman, expressing a desire to return to a more patriarchal world?

Bond certainly appears to feel threatened. Connery’s performance, especially his delivery of “You don’t think it gave me any pleasure, do you?”, conveys how disingenuous Bond is here: yes, he did gain pleasure from having sex with Fiona.

This attack on her vanity is what pushes her over the edge, leading her to launch into a tirade:

“But of course! I forgot your ego, Mr Bond. James Bond, who only has to make love to a woman and she starts to hear heavenly choirs singing. She repents and immediately returns to the side of right and virtue. But not this one. What a blow it must have been, you having a failure.”

The dialogue in the film is more explicitly a critique of Bond’s relative lack of agency in Goldfinger: all he had to do to save the day was have sex with someone. This time, Volpe makes clear, will not be so easy.

Wilting under this withering character assassination Bond can only concede: “Well, can't win them all.”

In a 2018 article ahead of the publication of her seminal 2020 book Bond Girls, Monica Germana gave her reading of this scene:

“Fiona’s pungent sarcasm is a fit riposte to Bond’s sexual innuendos and patronising attitude to women. It is her desire that threatens Bond – he previously tells her “she should be locked up in a cage” – rather than the other way around.”

Volpe must be killed soon after such a speech: her threat to traditional gender roles is too great. Such are the rules of popular cinema! But while her death is certainly memorable, we remember her challenge to social norms even more.

Germana rightly urges us to confront 007’s sexism, as Volpe does, rather than seek to sanitise it by pretending it doesn’t exist.

Volpe is particularly alluring for queer people: she is othered by her foreign accent, her outlandish hyperfeminine attire and, perhaps most of all, by her readiness to break the social rules that prescribe and proscribe masculine and feminine behaviour.

You go gurrrrrls

Volpe: May I cut in?

Girl in Kiss Kiss Club: You should've told me your wife was here!

Bond [to Volpe]: Do you come here often?

Moneypenny: Every man in Europe's been rushed in. And the Home Secretary, too.

Bond: His wife's probably lost her dog.

With the exception of the Home Secretary, no one is married in Thunderball. Another exception could be Colonel Bouvar, although he may be the same person as his wife and she may not actually exist, so not exactly ‘heteronormative’.

We live in a heteronormative world, where the relationship held up as an ideal is one heterosexual man and one heterosexual woman, both of who must actually exist and not be created solely for the purpose of faking one’s own death and evading James Bond.

In a heteronormative world, this man and woman get married, live out their lives sticking rigidly to the roles expected of them based on their genitalia and then die, ideally having secured some kind of postmortem future for themselves by passing on some of their genetic material by bumping their genitalia together and producing part-clones of themselves. Okay, it all sounds a bit mad when you put it like that. And yes, I’m being flippant but I think I’m entitled to a degree of flippancy having grown up in this kind of world, a world where alternatives were actively shut down by the institutions (government, education, the law) that should have been supporting me in living a more or less satisfying life.

Being gay meant this was never a possibility in my mind and I’m fortunate, at least, that I was in a privileged enough position that I didn’t have to live a lie even longer than I did. Had I been born into another culture, or even just a few decades earlier, my options might have been a lot more limited.

A lot of people are pressured into getting married and having kids. I felt the pressure, but I resisted. Okay, so I got married not long after same sex marriage became possible. I bought into a heteronormative institution and if that makes me somewhat ‘homonormative’ then fine. Whatever. It’s not an everything or nothing thing - we can pick and choose!

If marriage is a hallmark of heteronormativity, Thunderball presents us with a world which is distinctly unheteronormative.

Heteronormativity is so much the norm that it’s easier to spot by its absence. This is highlighted in the scene in the Kiss Kiss Club where the girl Bond takes on the dancefloor as cover assumes Fiona Volpe, cutting in, is his wife. The joke is, were there ever two people less likely to settle down into marriage with each other - or anyone else for that matter - than James Bond and Fiona Volpe? It’s doubly amusing because Bond’s line - “Do you come here often?” is such a cliched pick up line that we can’t imagine Volpe ever being receptive to it. It’s a line you would ordinarily hear in a heteronormative environment, where people go through the various stages of dating, working their way - over a socially respectable period of time - from a peck on the cheek to sex. In other words, everything James Bond finds tedious.

And not just James Bond. The Girls of Thunderball are just as impatient to get what they want.

Bond has already tried out this line - “Do you come here often?” - earlier in the film, on Domino. After this attempt to pick her up fails, Bond fakes boat trouble. Dialogue in the shooting script but cut from the film reveals that Domino was fully aware of Bond sabotaging his own motor but she still goes with him anyway. Even so, in the film it’s obvious that Domino knows what he’s up to. When he suggests lunch by the pool she reminds him about his urgent appointment that he’s now forgotten about. When she calls him on his continual questioning he changes tack - telling her that’s what he’s doing! - and offers her conch chowder, which she identifies as an aphrodisiac.

Unbeknownst to Domino, Bond’s urgency has less to do with him wanting to have sex with her for his own pleasure and more to do with finding out vital information related to his mission. During their next meal together, later that same day, when Bond is again pumping her for information, they continue talking at cross-purposes. Trying to work out if the Disco Volante will be populated when he looks her over later, Bond asks “Are you sleeping aboard tonight?” She tells him “I hoped you'd not be so obvious.”

For her part, Domino can be just as obvious. Her parting line to Bond is “You know where you can find me”. Even before Domino asks Bond to kill Largo, there’s more than a hint that she wants him to help her get rid of him in some way, or at least shake up the status quo.

A clear reminder that we’re watching characters navigate a heteronormative society is Domino being so embarrassed at being Largo’s “mistress” that she pretends to be his niece. Bond gallantly tells her he would not have called her what others might: a “kept woman”. He would pass no judgement whatever she labelled herself. That Domino is ashamed in the first place exposes the pressure she feels in heteronormative Bahamian society as an unmarried woman in a sexual relationship with a man. Largo is not even married, so Domino cannot be his mistress but is, more accurately, his girlfriend. It’s a double standard of course. Bond’s preference for relationships with married women is well known: they keep things uncomplicated, even if he does have to deal with the odd jealous husband. There is no exact male equivalent for ‘mistress’ in the sense of a man being the sexual partner of someone who is married, although some have suggested using ‘paramour’ (which sounds far more romantic) or ‘misteress’ (which just sounds laboured).

Domino’s self-conciousness about how her relationship is perceived by wider society endears us to her. In all other ways, she is impressively resilient. When Bond warns her he’s about to say something hurtful (after ther underwater sex) she tries to pre-empt him breaking it off with her, voicing aloud herself what she imagines he is about to say: “You're going away. ‘Sorry, my dear. It's all over’...” Brushing her hair and not looking at Bond, she makes it clear that this would not really bother her. Domino can be just as transactional as 007 - and deadly.

Domino is the only Bond Girl who gets to kill the main villain. And she doesn’t feel an iota of remorse for having done so.

Domino has this in common with the protagonists of many slasher horror films. It’s well documented that many queer people identify with what Carol Clover called ‘Final Girl’ characters, perhaps because the character is made to suffer but ultimately emerges as the victor, rather than falling prey to the monster as their victim. Although the consensus is that the modern slasher film did not begin until 1978’s Halloween, there were progenitors: the end of 1960’s Psycho has the initial victim’s sister survive the horror of her basement encounter with Norman Bates, even if it is John Gavin (who nearly played Bond in Diamonds Are Forever) who disarms him.

We never find out what would have happened to Domino had Largo carried out his plan of applying heat and cold ‘scientifically’ to her body, but we gather he would have gained sexual satisfaction from his nonconsensual act. Until this near-torture scene, we don’t really feel a great deal of antipathy towards Largo: with the exception of poor Paula and Domino’s brother, deaths for which he is indirectly responsible, he’s mostly been shown offing people within his own organisation. But his mistreatment of Domino makes us bloodthirsty: he’s undoubtedly a monster who deserves a harpoon to the chest. And it’s perfect that Domino is the one to deliver it.

Trans artist and Bond fan, Spencie d’Entremont finds Domino to be the ultimate Bond Girl: “Dominique Derval is one of the few characters whose nickname [Domino] is their iconography. This is reflected with a black and white wardrobe throughout the film. I adore characters whose clothing becomes a visual representation of themselves.

“I was so pleased to hear Claudine Auger’s real voice on YouTube. Auger’s voice is a lot lower than Domino’s. It sounds sexy and demure. She speaks with a lower tempo and resonance. Auger’s real voice is closer to my own. As I mature into my transition, I have learned to love my own vocal resonance. It is my own and it makes me happy.”

Bond Girls will return in…

It’s curious that On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was planned as the fourth Bond film and was even announced as such on early prints of Goldfinger. The change of plan was due to Eon feeling the pressure of a rival production led by Kevin McClory, so they combined forces with McClory rather than risk competing. Goldfinger’s director Guy Hamilton jumped ship at this point, wary of having to make underwater fight scenes thrilling. Hamilton had been excited by the idea of helming On Her Majesty’s Secret Service because it was essentially a love story. But instead of having Bond fall in love with one woman and get married (albeit very briefly), after Goldfinger, the filmmakers went as far away from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service as they could: Thunderball has more Girls than ever before.

Not that the Home Secretary notices. Even if he didn’t have two stolen nuclear bombs taking up some of his cognitive capacity, he would still probably refer to all of the assembled MI6 agents, including at least one woman, as “gentlemen”. Publicity photos show there is a woman sitting at the table but, in-keeping with how certain other feminine touches were pruned out of Thunderball along the way, she’s edited out of the finished film.

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

Amidst the chaos of Thunderball’s final act there is an unintentionally hilarious shot of a Disco Volante crew member bringing up a bottle of champagne in an ice bucket and then more shots of him being knocked asunder as Bond causes the Disco to accelerate. For years, this puzzled me. Largo’s plot has basically crashed and burned and they’re popping open the champers?!

The champagne arriving is a surviving remnant of an earlier version of the climax.

We know from Richard Maibaum’s notes he made following the first viewing of the film’s rough cut that there was additional dialogue here, with Largo ordering a round of celebratory drinks for his men. This was at odds with the frantic mood required for an exciting grand finale.

With only one bomb still at large, an additional stakes-raising line of dialogue had to be added in post-production: when Largo tells his crew (and the audience) that there is still one bomb aboard, watch carefully and you will see Adolfo Celi is turned away from camera when this line is delivered, giving the editorial team the window they needed to slip words into his mouth. This must surely be the most dubbed Bond film, with barely any of the principal actors speaking in their own voice, which by itself gives the film a slightly trippy, disembodied camp energy.

However, the shots of the champagne being delivered had to stay in the scene because they also show Bond pulling down the Disco’s throttle. Additionally, the ice bucket spilling its contents sells the idea that the Disco has rapidly accelerated.

The footage of the Disco hurtling perilously close to rocks has obviously been sped-up, giving it a silent film vibe. Added to this, the dialogue in the finished film’s climax is minimal, with Barry’s score doing a lot of the storytelling. From Felix wishing Bond “good luck” to the end credits there are only 126 words spoken. Most of these are short interjections, like “Come on!” “Fire!” “More!” “Over there!”. Two of them are “aye aye”.

This is the first entry in Connery’s Pink Trilogy, which continues with You Only Live Twice (long-sleeved shirt) and Diamonds Are Forever (short, chunky tie). Matt Spaiser of Bond Suits observes: “Ultimately, colours do not have genders and James Bond is no less of a man when he wears pink. Few men would attempt an all-pink outfit, but James Bond never loses his masculine cool in this look.”

Bond wears several shirts with camp collars (meaning they lie flat rather than stand up). Why these collars are called ‘camp’ is a mystery, although Matt Spaiser speculates it may be because American English associates ‘camp’ with summer recreation, when you would ordinarily wear a shirt with a camp collar. If this is indeed the case, this means the name for the shirt collar may be related to the British English ‘camp’, which we use to describe something which has a camp attitude or sensibility, I.E. something which is over the top, artificial, acting against type and silly. A Bond film fits this description very well!

The word ‘camp’ has been used to refer to a place where soldiers ‘camp out’ for centuries. It’s this meaning which eventually extended to include anywhere where a group of people gather temporarily, such as American teenagers going off to ‘camp’. So where did ‘camp’ in the British sense (over the top, silly, etc) come from? Linguist Paul Baker points out that, in the 16th Century, French King Louis XIV staged battle practices at his military camps which were gloriously overblown. This possibly sparked off using ‘camp’ to describe something which is over the top.

This red rubber ensemble helps us, the film audience, pick out Bond in the overblown final battle but is hardly the most practical: it doesn’t exactly make Bond invisible to the enemy! Perhaps he was hoping to stop by a fetish bar afterwards?

In the shooting script, Bond’s gag about all of Europe’s agents converging because of the Home Secretary’s wife’s dog going AWOL was originally a cheeky wink to Dr Who, which started broadcasting in 1963 and was already a British institution by the time of Thunderball’s production (an institution, incidentally, whose first episode was produced by a woman and directed by a gay British-Indian man.)

Maurice Binder’s title sequence can always be relied upon to prime us for the camp delights that await us in the rest of the film. This time, we’re under water, appropriately enough. Pushing his ‘fluidity’ theme to its limit, we are treated to what appears to be mermaids in love. It’s a fleeting impression, shattered the instant we see the women’s feet. Never mind: they’re only humans! Although they’re not wearing aqualungs, which immediately makes them better at Bond and Domino at this sort of thing. And the sheer amount of bubbles they’re generating would suggest they’ve also outdone Bond and Domino when it comes to fish-frightening.

Verdict (003 out of a possible 007)

The gentleman’s a killer but the damoiselles are just as dangerous. Although the scripts of Thunderball reveal the filmmaker’s efforts to present a more masculine Bond, the women rise to meet this challenge. Thunderball points a harpoon at heteronormativity and takes its best shot, hitting the mark more often than not.

References

Birkenshaw, C. (2023) ‘Feeling the Weight of Cultural Capital’s Water.’ Carnegie Education. Available at: https://www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/blogs/carnegie-education/2023/06/cultural-capital/

Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L. 1992. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1998) ‘On Male Domination.’ Le Monde Diplomatique. Available at: https://mondediplo.com/1998/10/10bourdieu

Burg, B.R. (1982) Sodomy and the Pirate Tradition. New York: NYU Press

Burlingame, J. (2012) The Music of James Bond. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Chowdhury, A and Field, M (2015) Some Kind of Hero: The Remarkable Story of the James Bond Films. Cheltenham: The History Press

Clover, C.J. "Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film.” Representations, 20 (1987), 187-228

Funnell, L. (2020) ‘Patricia Fearing, Sexual Violence, and Thunderball’ LisaFunnell.com, 10th february 2020 Available at: https://lisafunnell.com/2020/02/10/patricia-fearing-sexual-violence-and-thunderball-1965/

Geelhoed, F. (2022) ‘‘What DO you do?’ Asexual coding in the James Bond universe’ Licence to Queer Available at: https://www.licencetoqueer.com/blog/what-do-you-do-asexual-coding-in-the-james-bond-universe

Gibson, L. (2018). ‘Challenging the Gender Binary in Bond Films: Bond Girls, Female Villains and James’ in Fashion, Agency, and Empowerment: Performing Agency, Following Script. London: Bloomsbury

Goh, J.X. and Hall, J.A. (2015) ‘Nonverbal and Verbal Expressions of Men’s Sexism in Mixed-Gender Interactions.’ Sex Roles 72, 252–261 (2015).

Green, J. (2023) ‘Poker n.’ Green’s Dictionary of Slang Available at: https://greensdictofslang.com/search/basic?q=poker

Jalili, C. (2019) ‘Your Guide to (Successfully) Having Underwater Sex’ Cosmopolitan November 27th 2019 Available at: https://www.cosmopolitan.com/sex-love/a29832758/underwater-sex-guide/

Playboy (1965) ‘Playboy Interview: Sean Connery’ Playboy, November 1965

Rich, A. (1980)’ Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence’ in Women: Sex and Sexuality (Summer, 1980), Vol. 5, No. 4

Simmons, B. (1987) Nobody Does It Better: My 25 Years of Stunts with James Bond and other Stars. New York: Sterling

Smith, K. (2015) ‘‘Keep Mum, She’s Definitely Not Dumb’: The Complex and Cunning Femme Fatale in Espionage Fiction and History’’ in: Farnell, Noiva, Smith. Perceiving Evil: Evil Women and the Feminine. Interdisciplinary Press.

Smith, K. (2017) ‘Seduction and Sex: The Changing Allure of the Femme Fatale in Fact and Fiction’ in Re-visiting Female Evil: Power, Purity and Desire. Leiden: Brill Publishers

Spaiser, M. (2022) ‘The (00)7 Times James Bond Wears Pink’ Bond Suits. Available at: https://www.bondsuits.com/the-007-times-james-bond-wears-pink/

Williams, D. (105) ‘The GQ guide to James Bond: Thunderball’ Gentleman’s Quarterly, 5th May 2015 Available at: https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/thunderball-james-bond-guide

Thank yous

Thanks to Martine Beswicke for bringing Paula to life and putting up with me asking questions about her whenever we meet.

Claire Birkenshaw introduced me to Pierre Bourdieu and his fish metaphors. Thanks for your erudition and friendship Claire.

Jon Auty, stunt expert non-pareil, was of invaluable help with the Bob Simmons section.

Matt Spaiser threw around the etymology of ‘camp’ collar with me and came up with the best theory I’ve heard.