Queer re-view: The Man With The Golden Gun

Like a bottle of Phuyuck ‘74, The Man With The Golden Gun has aged… interestingly. Officially, 007 is hot on the pursuit of (*checks notes*) something-to-do-with-solar-energy. But the real drama is whether Bond will be able to save his fractured masculinity in a ‘mano a mano’ duel to the death with Francisco Scaramanga.

If this is your first time reading a re-view on LicenceToQueer.com I recommend you read this first.

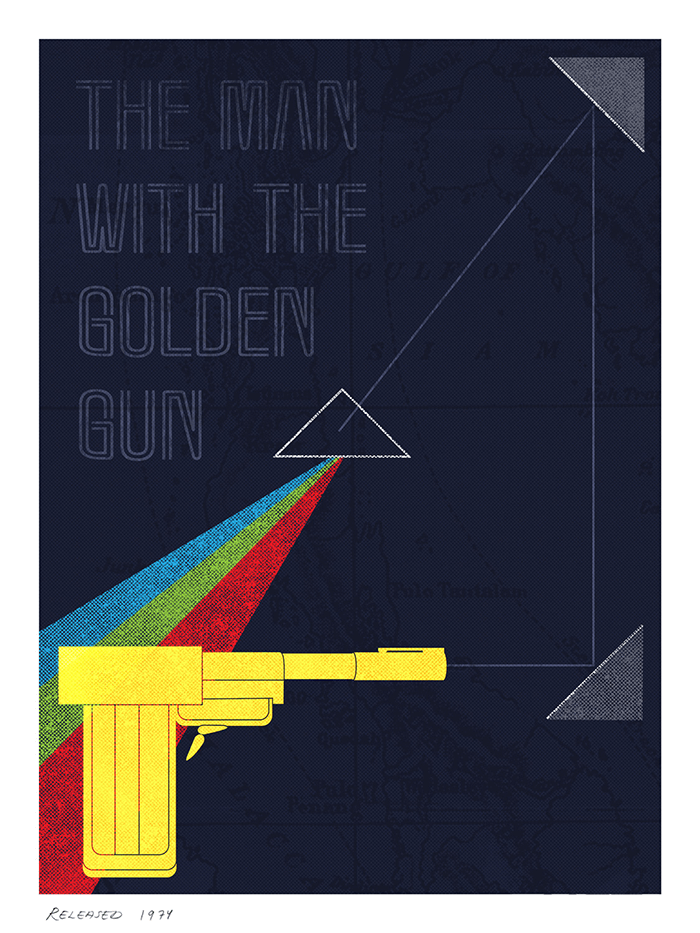

‘Inspired by The Man With The Golden Gun’ by Herring & Haggis

“The name’s Bond, Flaming Bond?”

For all of The Man With The Golden Gun’s attempts to persuade us that it’s the world’s energy supply at stake, what’s really under threat in this film is Bond’s masculinity.

The surface story, which has everyone chasing a MacGuffin in the shape of a ‘Solex agitator’ around Southeast Asia, is a pretext for orchestrating a showdown between 007 and Francisco Scaramanga, who provides the film series with its first true ‘dark side of Bond’ villain, the model for many that follow.

Screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz was nakedly honest about his intention to make Scaramanga into Bond’s “alter ego” and indeed the two characters have more in common than Bond would like to admit. In the pivotal ‘seduction scene’ across a lavishly-laid dining table, a Bond film tradition as far back as Dr. No, Bond is goaded by Scaramanga. He is visibly repulsed at Scaramanga’s insistence that they are equals: “We are the best”. When Bond protests too much Scaramanga presses on: “You get as much fulfilment out of killing as I do, so why don’t you admit it?”

As we shall see, the word ‘admit’ recurs throughout the screenplay of The Man With The Golden Gun, always used by or in relation to Bond. Cumulatively, it creates the feeling that Bond is hiding something.

Perhaps it’s Moore’s performance here which is also responsible for this feeling that we’re only seeing the surface and not being allowed to penetrate Bond’s inner life. I have always found Roger Moore’s performance as Bond to be - in the most positive way possible - superficial. Don’t get me wrong - I love Roger Moore in anything, especially Bond. But his Bond is considerably more arch than Connery’s. There’s a brazen lack of sincerity across his seven films, except in a handful of scenes. The Man With The Golden Gun shows Bond at his most insincere. Even the brief ‘let’s be serious’ moment with Goodnight, where Bond reflects on the dangerous, ships-that-pass-in-the-night nature of their profession, is undermined by their drinking of a comically labelled bottle of wine (Phuyuck ‘74) and the nagging feeling (confirmed only seconds later) that Bond is putting on a carpe diem mindset just to get his colleague into bed with him.

Even the bed-hopping in this film is superficial. Bond ‘beds’ two women - at the finale it’s Goodnight, because she’s the damsel, the dragon (Scaramanga) has been slain and the hero needs his reward. As people like Vladimir Propp have shown us, thus was it ever so. The tussle with Goodnight is a cut-to-the-end-titles consummation delayed from the middle of the film when Maud Adams’ Andrea Anders interrupted them, forcing Goodnight to take refuge in Bond’s closet. You can probably see where I’m going with this.

Yet again, Bond uses sex with a woman solely to get information. Andrea knows all about the Solex agitator. He wants this knowledge. In return, she wants Scaramanga dead. It’s entirely transactional. There’s little in the way of attraction between them - they are using each other for mutual benefit. In fact, Moore plays it almost as if the experience is somewhat inconveniencing.

The other woman Bond has a sexualised encounter with is Saida, the belly-dancing owner of the bullet which killed a fellow agent which Bond needs to obtain. Interestingly, Saida was originally written as overweight and caked in make-up. The idea was to play the scene for laughs with Bond, again, having to put ‘queen and country’ ahead of any personal scruples. This would have ensured that this scene was also seen as purely transactional.

In later films, Moore’s Bond has uncomplicated - and apparently pleasurable - couplings with many women. In The Man With The Golden Gun, the sex is perfunctory. It’s just something we expect James Bond to do, so he needs to get on and do it, even if it brings him no joy.

There are many gay men who have experienced this first-hand: having to pretend to enjoy sex with women just to meet society’s expectations. At a painful extreme, some gay men try bedding many women in attempts to turn themselves straight. Others claim to have many female notches on their bed posts, bragging about their encounters, so they appear to be straight. This is a classic example of what sociologists call ‘hypermasculine’ behaviour: acting in conspicuously ‘manly’ ways to compensate for not feeling ‘normal’.

Moore is not, in many regards, the ‘manliest’ Bond. Again, I don’t mean this pejoratively. But the reality is he is far less physical than Connery in fight scenes. Although he has some brutal fights, including the one in Saida’s dressing room here, they are usually more conspicuously choreographed than Connery’s. Moore himself said he compensated for his less physical portrayal by giving his Bond more ‘charm’. But is ‘charm’ synonymous with sexual prowess?

One of my favourite moments in The Man With The Golden Gun comes at the end of the Saida’s dressing room scene. Saida herself provides the setup. Realising that the golden bullet from her belly button has been lost in the melee between Bond and the club owner’s thugs, she announces “I’ve lost my charm.” Unbeknownst to her, the ‘charm’ has been accidentally swallowed by Bond who stops at her dressing room door just long enough to tell her “Not from where I’m standing”. It’s a brilliant bit of wordplay to round off a scene that could have been played ‘straight’, with Bond gaining another female conquest, but instead ends with Bond, rather conveniently, getting to leave with both his mission accomplished and his chastity intact.

Decorated with attractive women The Man With The Golden Gun may be (even a gay man like me can appreciate the charms of Ekland, Adams, et al), but no one - Bond or Scaramanga - seems all that interested in them. They’re rather more fascinated with each other and their guns, especially in Scaramanga’s case (see Villains below).

Moore’s Bond, like Connery’s, is a great shot. He proves this early on when he threatens Lazar into giving him information by aiming for his crotch and hitting precisely where he aimed for. “Speak,” Bond says, “or forever hold your piece”, conflating power with sexual potency. The villain threatening Bond with castration is a staple of the series (Goldfinger with his laser, Le Chiffre with his rope torture) but here it’s Bond threatening another man with the loss of his genitals. The hero has taken on a trait we typically see in the villain.

Bond is not an especially likeable person for much of The Man With The Golden Gun. His treatment of the women - especially poor Andrea - is abominable. He also mansplains a lot. He does it to M immediately after the Bond-less (apart from in dummy form) pre-credits and title sequences, regurgitating everything he knows about Scaramanga. He also does it to Scaramanga himself, explaining to the villain how his own facility works. In both cases, it’s necessary from a story-telling point of view, but putting the exposition in the mouth of Moore makes Bond sound like a know-it-all who enjoys lording it over everyone else.

Bond warns Scaramanga to not put his finger “or anything else for that matter” (yet another penis reference) in his vats of freezing liquid helium (Bond gives the exact temperature, as he does with everything). For his part, Scaramanga is utterly nonplussed by Bond’s mansplaining. All he’s interested in is the pistols at twenty paces duel, which brings the film’s major concern - Bond's masculinity - into sharp focus.

Scaramanga describes the duel as “the only true test for gentlemen”. Bond’s pithy comeback is to question Scaramanga’s manliness, saying “I doubt you qualify on that score”. And yet, when you put the two men side by side, there’s not much to tell them apart.

Aside from Scaramanga’s superfluous third nipple, they are not even physically dissimilar. Bond must think so too, posing as Scaramanga to infiltrate the hideout of Hai Fat, his esrtwhile employer (soon to be victim). It’s almost like he’s ‘trying out’ being the villain. But it doesn’t take. He discards this identity as soon as he is out of Hai Fat’s compound, tossing away the Q branch-issued third nipple with disdain.

When Bond and Scaramanga do come to blows, Bond is the more honourable one, waiting until the count of 20 to turn around, only for Scaramanga to have scarpered. Does this make Bond more conventionally ‘manly’? Arguably, Bond’s shooting of Scaramanga does the opposite. It’s somewhat underhand and could be anti-climactic for viewers not keyed into the film’s symbolism.

Although it remains one of the more superficial Bond films, with barely a glimpse into Bond’s inner life, The Man With The Golden Gun takes on slightly trippy psychological qualities in the finale. Bond gets a bit lost in Scaramanga’s Funhouse, both figuratively as well as literally. Scaramanga’s lair functions as a visual representation of Bond’s mental model of himself. Just before killing Scaramanga, Bond even has to confront multiple mirror reflections of his ‘self’, showing his psyche to be fractured. Bond can only emerge unscathed, psychologically and literally, after he has killed his ‘dark side’ (killing what he is not, in the form of Scaramanga) and once again become a singular ‘James Bond’ (what he is).

Tellingly, Bond can only kill Scaramanga after he changes into his most iconic look - a dark suit. Bond’s wardrobe throughout The Man With The Golden Gun is mostly on the casual end of the spectrum, surely something that was intentional. Although he dresses up a couple of times (including in his almost-as-iconic white dinner jacket and a charcoal grey two piece), the film waits until almost the end to put him in his most ‘classic’ of looks. As we will see time and time again, Bond uses clothing like armour. He uses it to cover up his vulnerabilities. This time, it also allows him to hide in plain sight. Scaramanga realises, too late, that the immaculately tailored 007 dummy that we saw him shoot the fingers off in the pre-titles sequence is in fact the real 007, attired in the dummy’s clothes.

Bond literally disguises himself as himself. We are left with the impression that Bond has embraced the persona he shows to the world. And not just in terms of clothing: he adopts the dummy’s quintessential ‘man of action’ stance as well.

Just as ‘James Bond’ is a social construct, still being renegotiated with the audience by Moore in only his second adventure, a ‘man’ is also a social construct. The Man With The Golden Gun’s leading man puts on a brave show of manliness but, perhaps because Bond spends most of the film in the shadow of the eponymous Man With The Golden Gun, he leaves us with the impression that’s he’s not terribly comfortable in his own skin.

Friends of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

In what is widely considered to be one of the ‘campiest’ Bond films (see below), M is used to ground the events in some recognisable reality. He’s the ‘straight man’ as it were. He takes his fair share of the exposition, linking the Macguffin to real world concerns (the energy crisis is briefly precised, still a pressing matter today as it was in 1974). He also has a priceless reaction shot that follows on immediately after the campy triple whammy of Sheriff Pepper’s return/the corkscrewing car stunt/Scaramanga’s flying car. His look of sheer incredulity brings us crashing back down to reality, giving the audience permission to think ‘yes that was daft, now let’s move on’.

M always wants to ‘straighten out’ 007, disapproving of his lifestyle, particularly the womanising. Here he berates Bond for gallivanting through the ‘World of Suzie Wong’, a reference to the novel and film of that title in which another westerner travels to Hong Kong and has a relationship with a prostitute. When Bond cannot understand who would want to kill him, M singles out “jealous husbands” first before adding “outraged chefs, humiliated tailors”. It’s not just Bond’s ways with women he dislikes but also his pedantry with food and clothing. The scenes between M and Bond regularly come across as a parent figure expressing displeasure at their child’s ‘lifestyle choices’. Unlike queer people, they are choices for Bond. He was not born this way, which probably makes M all the more frustrated.

M even gets to do his first ‘coitus interruptus’ scene, his phone call literally interrupting (albeit briefly) Bond and Goodnight’s copulating. The scene is repeated, with additional authority figures doing the interrupting, at the end of the next three Moore adventures. Q gets the job with his ‘snooper’ robot in A View To A Kill. M takes a break until The World Is Not Enough, with Judi Dench doing the disapproving. It’s almost he/she doesn’t want Bond to have his ‘reward’.

Q’s most significant contribution is a prosthetic nipple. As Bond “admits” to his colleagues “it’s a little kinky”. Q also has another expert to bounce off, striking up a professional bromance with Colthorpe, the gun expert, performed by James Cossins, who played several queer roles on screen and other characters described in contemporary reviews as “fussy” (often code for ‘queer’).

After eight films, Moneypenny is getting impatient with Bond, refusing to be called “darling” anymore. By this point, she must be thinking: why is Bond not taking these massive hints? Why is he not interested? There’s only so many times a girl can put herself out there... Lois Maxwell gives her most prickly performance and will soften up again by the next film.

Sheriff J.W. Pepper returns, this time with wife in tow, although he soon ditches her for a high speed pursuit with “That English secret agent! From England!” To be fair, he is technically kidnapped by Bond who just drives the car he’s sat in the passenger seat of straight through the showroom window. Up to that point though, Clifton James gives us a caricature of a hen-pecked husband not impressed by his wife spending their tourist dollars on tat for the mantelpiece back home in Louisiana. One of the few ‘normal’ heterosexual relationships in the Bond series is not exactly presented as idyllic.

Shady characters: Villains

Scaramanga is the archetypal dark side of Bond, a character-type we see repeated throughout the series following the example he sets in The Man With The Golden Gun. And yet, he’s not all that dark. In fact, for most of the film he’s pretty jovial.

Jung would have called Scaramanga Bond’s ‘shadow’, the term he used to describe the part of our unconscious minds made up of anything society considers unacceptable. These may be desires which are not ‘normal’, animal instincts and anything else we try to repress because we know others might think less of us if we let them into the light.

But there’s nothing very obviously repressed about Scaramanga. If he has desires the audience might consider ‘dark’, he has no such hang ups about them. For all of the horror movie baggage Christopher Lee brings with him, his portrayal of Scaramanga is refreshingly light. He practically skips towards Bond after he lands on his island hideaway, seconds after giving a “vulgar display” by shooting the cork from a bottle of Champagne. He’s confident in his abilities with a gun to the point that, when Bond queries whether their duel will be a fair fight, with his six bullets to Scaramanga’s one, Scaramanga puts a full stop on the conversation: “I only need one”.

The man, as it says in the film’s title, is defined by his gun. He even frames his “mano a mano” battle with Bond in terms of their guns: “My golden gun against your Walther PPK.”

Besides his gun, we learn little else about him. Aside from a splurge of exposition at the beginning, there’s only a back story about his love for an elephant (taken from the Fleming novel) and how he developed a taste for killing. But although this monologue is memorably delivered by Lee, this is almost thrown away by the film which cuts away to Bond exploiting Scaramanga’s distracted frame of mind to salvage the Solex agitator off the floor.

He has a taste for a Black Velvet, the cocktail he’s drinking in the pre-credits sequence made from Guinness and Champagne, a favourite of Bond’s in the novel of Diamonds Are Forever. It’s quickly established that he has a home gym (so he’s arguably hypermasculine?) and a steam bath (so he’s not?). And he appears to take no pleasure in his girlfriend Andrea Anders towelling down his legs.

His sexual proclivities are spelled out by the title song and in dialogue a little later from Andrea: he only has sex before he kills. But later this is contradicted when he returns from a kill and starts rubbing his pistol in an obscene fashion over Andrea’s chest and lips, suggesting he’s inclining towards a repeat performance.

It’s a deeply disturbing scene that serves to make the Freudian subtext overt but ends up muddying it. Are we to believe that Scaramanga’s power with a pistol compensates for his impotence in the bedroom? But only some of the time?

Perhaps things would have been clearer if the filmmakers had included a key detail from the novel: that Scaramanga is almost certainly homosexual. In the novel, Scaramanga’s irrational behaviour can only be explained by his attraction to Bond. There’s barely a a hint of this in the film. The film’s Scaramanga is actually one of the least ‘gay’ villains in a pantheon that includes many. Perhaps because Moore’s portrayal of Bond in this film is so hypermasculine there would have been nothing for Lee to play off.

His otherness is mostly confined to his third nipple, which Hai Fat says would confer him with “sexual prowess” in some cultures. Despite this, Lee’s Scaramanga is really not very interested in anyone in that way, especially women. He remarks, of a scantily-clad Britt Ekland: “I like a girl in a bikini. No concealed weapons.” There’s not even a hint of lasciviousness. Having her attired thus is merely pragmatic. When he shows Bond around his facility, Bond questions him about the need for staff. Scaramanga says “Nick Nack does for me very well” (presumably not in a sexual sense!), following it up with “usually it’s just the two of us”, completely forgetting about the power plant operator Kra (played by an uncredited Trinidadian former wrestler Sonny Caldinez) and Andrea who had been living there with them until very recently.

Whatever Scaramanga’s preferences, the film gives us enough to label him a ‘sexual deviant’. And yet he seems more at ease with himself with only a hint of feelings of inferiority. When he destroys Bond’s plane with his gigantic heat laser he says: “You must admit, Mr Bond, that I am now undeniably The Man With The Golden Gun.” You can hear the capital letters. He is seeking Bond’s approval. But even when Bond refuses to give it in the seduction scene which follows, he has a stronger sense of self than 007 does. In Jungian terms, his persona and shadow are merged. He’s evil but he wants everyone to know he’s evil. And all he wants in life is to have the biggest gun. He is inextricably linked with his weapon. Lee plays him as someone who knows precisely who he is, even if the screenplay leaves the audience with some loose ends to tie up themselves.

Nick Nack is another of those characters we might file under the ‘you wouldn’t get away with this today’ category (see also Mr Wint and Mr Kidd, Oddjob, etc). Besides his height giving him blatant ‘otherness’, who knows what we are to make of Nick Nack? Memorable as he is, his motivation is muddled. He wants to take over from Scaramanga but is also sort of loyal and doesn’t help would-be assassins as much as he might. When Scaramanga is dead he tries to kill Bond and Goodnight out of… revenge? Even though the island is destroyed, surely Scaramanaga would have other assets elsewhere which he could inherit? Because he is so other, he must, by the end of the film, be put out of harm’s way so we can all leave the cinema or our sofas happy that the world has been restored to ‘normal’. A suitcase gets the job done. But even Bond can’t bring himself to drown Nick Nack. Doing so would leave a sour after taste. After all, even the most ‘normal’ audience members feel ‘other’ sometimes don’t they?

You go gurls!

If female characters are a way for some gay men to get into films ostensibly made for heterosexual audiences, the girls of The Man With The Golden Gun are some of the most relatable.

Like other characters in The Man With The Golden Gun (and people in real life), Mary Goodnight embodies contradictions. She is knowledgeable about her posting, taking great pleasure in explaining to Bond about why he is wrong about the scarcity of Rolls Royces around Kowloon (there are loads and they all belong to the Peninsula Hotel, somewhere I visited because of its connection with Bond).

She’s also been around the block a few times with Bond, or at least knows his reputation. When he makes his move she replies: “Darling I’m tempted. But killing a few hours as one of your passing fancies, isn’t quite my scene.”

“Ooooh burn,” we may think (or something of that ilk).

But girl power is short lived. Goodnight only waits until the next scene to appear in Bond’s hotel room. It’s a comic contrivance, with Goodnight quickly being shunted aside (into the closet no less) as soon as Andrea appears at Bond’s door offering to trade information. But it undermines Goodnight’s character almost to the extent that she ends up in the ‘prize’ category of Bond girl. If Bond gets his prize (the most beautiful girl) too soon the story might lose our interest. It’s this tension that Bond films often rely on to sustain our interest through the third act, even more so than a countdown to destruction.

Andrea’s intrusion means he has to delay his gratification with Mary Goodnight until the end of the film. For her part, Goodnight is furious at Bond, calling him out on his supposed prowess between the sheets. When Bond tells her he has no doubts that Andrea will bring him the Solex, Goodnight sarcastically says “James, you must be good.”

M describes Goodnight as an “efficient liaison officer” and in terms of narrative she efficiently propels the plot along. In fact, in terms of agency, she is responsible for almost everything that happens in the finale, from Scaramanga getting the Solex back from Bond, to setting off the chain reaction that will destroy the lair to almost killing Bond by pressing her bikini-ed backside against the laser controls. This is not strictly ‘agency’ by its traditional definition. She does most of these things by accident and this risks making her a figure of fun - the archetypal blonde bimbo. But she does a lot more than just hang around for Bond to come and rescue her.

Andrea Anders is one of the most tragic characters in all of Bond. Her nadir comes when she tells Bond, who is not interested in her sexually and only wants her for the Solex, “You can have me too if you like. I’m not unattractive.” All she wants is to be free of Scaramanga.

She’s the archetypal abused woman, the antecedent for villains’ mistresses to come, including Lupe in Licence To Kill, Valenka in Casino Royale and the similarly tragic Severine in Skyfall. Bond is savagely unsympathetic to her plight, telling her it would only be a pity if Scaramanga used one of his golden bullets on her “as they’re very expensive”. There’s a mismatch here, I would argue, between Bond at his most misogynistic and the audience’s sympathies. Perhaps this was the case in 1974 as well but I certainly feel it today. Just because she’s thrown in her lot with a villain doesn’t mean we don’t feel sorry for her inability to extricate herself.

“Stand back girls,” Bond tells Lieutenant Hip’s two nieces, seconds before they overpower an entire dojo of martial artists without Bond having to lift a finger. Okay, Bond does lift a finger, but only to push over an almost-unconscious bad guy.

It’s an hilarious, and bravely emasculatory, moment for a Bond film. Bond continuation author Raymond Benson said in his James Bond Bedside Companion that the moment causes the fight scene to “lapse into incredibility”, but would it be any more credible is this just because they're teenage girls? How about if Hip had nephews instead of nieces? Would we find it hard to believe if Bruce Lee appeared in a Bond film and did the same? We don’t struggle to find it credible that Bond fights his way singlehandedly through Kobe docks in You Only Live Twice. The closest we get to a woman doing the same is when Michelle Yeoh, entirely credibly, takes out a bike shop full of henchmen in Tomorrow Never Dies. That scene shares an almost identical payoff with that in The Man With The Golden Gun, although Pierce Brosnan plays it as if helping Wai Lin defeat the bad guys would have undermined her, treading on her professional (and lethal) toes.

Girl power indeed.

She’s only here for her name to provide the punchline to a one liner, but it’s worth pointing out that Chew Mee (the girl in Hai Fat’s swimming pool) superfluously points out that she’s not wearing anything under the water (this film sneaks more past the censor than most Bond films).

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

The lyrics to the title song, performed by Lulu, are appropriately suggestive for a film with so much phallic imagery (“Will he bang? / We shall see”) but the song as whole is nowhere near as obscene as that previous Barry/Black collaboration, Diamonds Are Forever. Maurice Binder’s scandalous titles make up the difference, with girls stroking the barrels of ‘guns’ (do we even need the ‘scare quotes’ at this point?).

Barry’s score is one of his most underrated. The lush orchestrations of the title theme are quite sublime. The camp element comes with the variations played in the pre-credits sequence (and briefly reprised in the final showdown). First we hear the ‘wild west’ version followed by a ‘Prohibition-era/gangster’ variation. A wonderfully malleable melody. If the film had been made a couple of years later we may even have had a disco version.

Bond pulls the ‘get a member of hotel staff to open this girl’s door’ trick that Connery had previously perfected. The waiter in question gives a superbly camp line-reading: “Oh a surprise!”

The canted-angle production design of the MI6 HQ inside the capsized Queen Elizabeth is to die for. Category is: chintzy 70s German Expressionist fantasy.

The Bottoms Up Club was a real place on the Kowloon side of Hong Kond. Its questionable signage (depicting, as in the film, naked buttocks) was removed in 1994 and it closed its doors in 2004. Just because it’s real doesn’t make it less camp.

The rock from which Scaramanga’s big-reflecting-dish-thingy emerges is described in the script as ‘mushroom-shaped’. In a less phallus-obsessed Bond film I might buy it, but not this time.

The slide whistle over the famous corkscrewing car stunt is a source of great consternation among the Bond fan community. Is it necessary? No. Does it take away from what is already a ridiculous sequence that begins with Bond crashing through a car showroom with a southern-states-of-America stereotype in the passenger seat and ends with the villain escaping in a flying car? Also no.

Bond cruelly throws shade at Goodnight’s car, calling her lovely olive green MG convertible an “inverted bedpan”. I mean, honestly.

Guy Hamilton came up with the idea of Scaramanga’s Funhouse. His original idea was to have Bond fight Scaramanga at Disneyland. I think the estate of Walter Elias Disney would have felt quite strongly about this.

When Bond asks Andrea how he will recognise Scaramanga she says: “tall, slim and dark”. Bond’s response is a classic: “So is my aunt.” Andrea also tells Bond about Scaramanga’s third nipple. Another classic reply, Bond pointing out that this is “probably the most useless information I ever heard, unless the Bottoms Up is a strip club and Scaramanga is performing”. The mind boggles at the possibility.

Queer verdict: 005 (out of a possible 007)

Very camp but also quite nasty in places - and more queer than most people give it credit for, The Man With The Golden Gun has a somewhat fractured identity. Although it tries hard to present Bond as a self-assured, hypermasculine hero, there are times when he’s less sure of himself than the calm, collected and ‘sexually deviant’ villain. For a film so concerned with masculinity, it’s a pleasant surprise that the girls stand out so much, perhaps because, although they are constantly down-trodden by the men, they keep getting back up again. An example for us all?