Queer re-view: The Living Daylights

Timothy Dalton delivers a 007 in transition. A stark contrast with Roger Moore’s portrayal only two years earlier, his new Bond opens up exciting new possibilities. In a story obsessed with border crossings and double crossings, will Bond be more prepared to cross lines in his personal and professional lives?

If this is your first time reading a re-view on LicenceToQueer.com I recommend you read this first.

‘Inspired by The Living Daylights’ by Herring & Haggis

“The name’s Bond, Flaming Bond?”

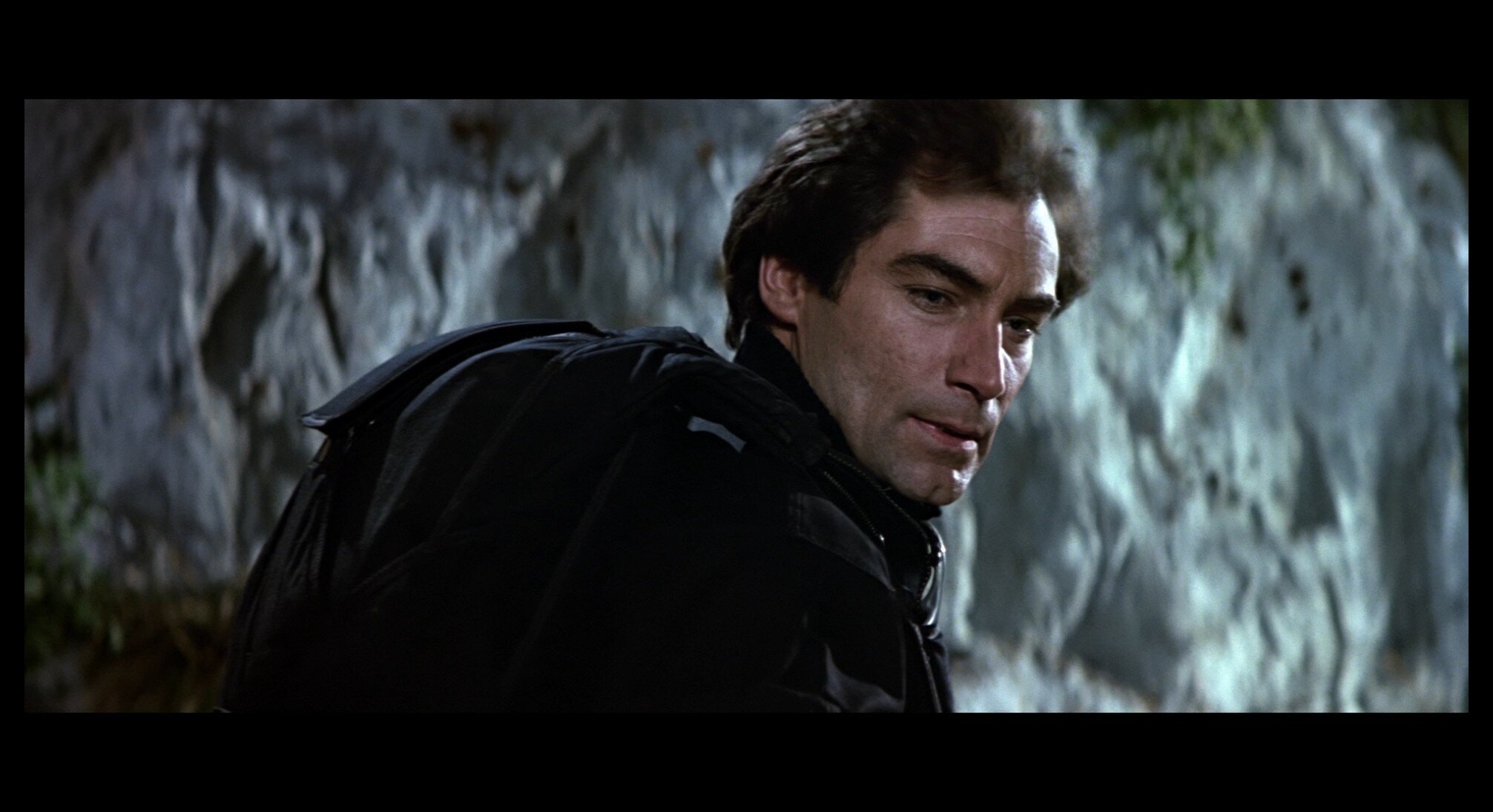

We’ve been here before and we’ll be here again. Bond has a new face, which we get our first proper glimpse of in an exciting zoom to close up. But how much has really changed?

The first film of each new Bond actor always feels thrillingly transitional to me. I know not everyone agrees, preferring the films where the actors have hit their stride. But each new transition is also an excuse to shake things up a little - or a lot.

I use the word ‘transition’ with great caution. I don’t intend to equate the swapping of one white cisgendered male actor with another with the experiences of queer people going through important life transitions. It’s nowhere near as momentous as coming out as lesbian, gay or bisexual. And coming out as trans is off the scale, as is the transition that follows. But I do wonder if queer people might be able to relate to Bond because he changes. And yet, we also relate to how he stays the same. Queer academic Claire Birkenshaw agrees: “The change in actor is like a transition. The core identity of Bond remains, despite the physical differences of the actors.”

Even physically, the Bond character exists within pretty tight parameters. Part of the fun of The Living Daylights’ pre-titles sequences is its playing with audience expectations and how far we’re willing to go with any visual changes. Before we even see Bond we are introduced to two other vaguely similar-looking men who also have a desk in the Double-0 section of MI6 HQ. The first one is blonde, so it can’t be him (see the furore about Craig’s casting prior to Casino Royale). The second one looks a bit more like the 007 we’re familiar with - and quite like Dalton. It’s unlikely anyone going in to this film would be unaware that Dalton is playing Bond of course. But when we finally get a shot of Dalton’s face, having two men precede him which don’t look ‘quite right’ sells the idea that ‘Yes, this is James Bond’. It’s a clever move, defining someone by first showing you what they are not.

But what about Bond’s “core identity”? When discussing Dalton’s Bond, fans regularly reach for adjectives such as ‘darker’, ‘harder’, ‘more serious’. These are all comparative descriptions, defining Dalton in relation to what has come before. James Bond has always been dark, hard and serious - up to a point. It’s all relative. And Brosnan’s lighter, softer, more frivolous portrayal only sharpened our perception of how dark, hard and serious Dalton had been as Bond.

Dalton’s appeal has increased over time because he is, to many, the most authentic incarnation of Bond. Dalton himself went to great lengths in interviews to stress how much he was going back to Fleming. But he was also consciously reacting against the parts of Connery, Lazenby and Moore he didn’t like and moving on, while still staying true to what the audience expects of ‘James Bond’.

It’s a difficult balancing act, and we all, engage with it throughout our lives: balancing social expectations (what other people think of us) against who we really are and who we want to be. Queer and non-queer people have this in common. It’s just that people who aren’t queer don’t have to ‘come out’, putting a label on something which is so socially taboo. ‘Coming out’, for most people, entails a rupture with the past. When I came out as gay, I worried a lot about people seeing me differently. A nuance about coming out that some people who aren’t queer understimate is that announcing you’re lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, non-binary or otherwise queer means they you are not becoming a whole new person but becoming more of the person you always were in the first place.

There’s a reason it’s called ‘coming out of the closet’.

Picture that item of clothing you bought a while ago which you never got around to wearing in public. You bought it because it looked good in the shop. It was something quite different - maybe a different colour that you usually wear, a different pattern, or a tighter fit. Your pulse raced a little at the thought of you going out in it. And when you tried it on in the changing room it fit perfectly. You said to yourself in the changing room mirror: “This suits me.” And deep down, you knew it was true. You wished you’d started wearing this sort of clothing years ago. The only problem was, when you got it home, you started to fixate on what other people would think when they saw you wearing it. You put it to the back of your wardrobe. In the meantime, you decide to carry on wearing the same sort of things you always wear. But the new purchase doesn’t end up at the charity shop. It lives on at the back of the closet, to be tried on another day (sorry, couldn’t resist).

Psychologists use the term ‘liminality’ to describe this disorientating feeling we get when we transitioning across borders and boundaries (‘limen’ means threshold in Latin). We don’t know if we’re coming or going and the reality is we’re in between the two. Things are no longer the same but they’re not yet different. Queer or not, we all experience these moments throughout our lives. James Bond is no different. Although he doesn’t ‘grow’ a great deal as a character and, besides marriage, he doesn’t go through many of the milestones of heteronormative existence, he is constantly on the move. Like a shark, Bond cannot stay still for long. This is particularly explicit in the Ian Fleming novels, where ennui/boredom/depression sets in if Bond is not given an excuse to jet off around the world on a mission.

Lots has been written about airports as liminal spaces - places where our identities can become dislocated, reduced and even recreated. But think of the number of times Bond boards a train, ostensibly to get from one destination to the next. I find it amusing how these sequences rarely make narrative sense, especially in the recent era where a plane would be the sensible option for the race-against-time situations (Casino Royale and Spectre are particularly notable here). The real reason Bond is on a train is because it gives the writers time to deconstruct his character a little, often with the principal Bond girl (in classic Hitchcockian style) asking the probing questions.

While The Living Daylights does not feature a train journey, it does contain an awful lot of vehicles and destinations. Bond definitely clocks up some airmiles in this adventure.

Even by the standards of Bond films, The Living Daylights is restless. You could even describe its 130 minutes running time as a ‘liminal space’ in itself. Its ludicrously labyrinthine plot moves from Gibraltar to Czechoslovakia to Austria to England back to Czechoslovakia back to Austria to Morocco to Afghanistan back to Tangier and finally back to Austria. And that’s just the nations as a whole, let alone the places within them that Bond shuttles between while sat in Aston Martin, Hercules plane, horse-drawn-carriage, cello case and camel.

It’s notable how all of these places could be described as liminal in their own right. Perched on the tip of Spain, Gibraltar has been a British overseas territory since 1713. It has a British identity despite being attached to mainland Spain (who, perhaps understandably, would like it back). Czechoslovakia was less than six years away from dissolution into Czech and Slovak republics when The Living Daylights was released. My family actually went on holiday there (before it was cool!) in 1991 and even as a nine year old I remember seeing the signs of transition everywhere. Every street vendor was selling off Soviet-era clothing and mementos.

Bond engineers two crossings across the Czechoslovakian border (a literal, not just psychological, liminal space) into Austria. Austria itself of course was divided into four occupation zones at the end of the Second World War, one for each of the United States, Soviet Union, United Kingdom and France. The Moroccan location chosen for the film is Tangier, a port city which has acted as a gateway between Africa and Europe for millennia. Finally, even in recent memory, Afghanistan has been the site of so many struggles for control. Bond steps into the fray during the final years of the Russians’ attempt to assert their authority, a failure that many credit with being instrumental in the fall of the Soviet Union.

The producers have always maintained that they never wanted to get involved in real world geopolitics. But to quote a later Bond in his first adventure, governments change, the lies stay the same. Bond locations are chosen because they open up possibilities for storytelling: they are places where disreputable people might linger just long enough before their adversaries catch up with them. Tangier in particular is a hotbed of spying activity. An “espionage haven” in real-life, it reappears on screen in a similar liminal role in Spectre as well as being the setting for character-defining action set pieces in The Bourne Ultimatum and Mission: Impossible - Rogue Nation.

Bond’s escapades do not look out of place in Tangier and the other The Living Daylights locations. Perhaps the only exception is the Blayden safe house, a quintessential country manor, but Bond has already left in his Aston Martin by the time the exploding milk bottles start flying.

You can’t discuss Bond’s liminal identity in The Living Daylights without bringing up detente, a word that first appeared in the screenplay of The Spy Who Loved Me and then kept making ever more conspicuous appearances, most notably at the end of For Your Eyes Only and, most memorably, in the jacuzzi scene of A View To A Kill, only two years before The Living Daylights.

The impending end of the Cold War means Bond’s job might be on the line. The producers sidestep the real world events in the USSR and their repercussions entirely in Licence To Kill but return to tackle the problem head after things have calmed down a little in GoldenEye, finding a way to justify Bond’s continued existence.

The original short story which inspired plot elements of The Living Daylights was originally entitled Berlin Escape because the attempted assassination (real, as opposed to phoney in the film) took place across the Berlin Wall. With astonishing prescience (luck?) the producers shifted the location from the West/East German border to Czechoslovakia. Two years after The Living Daylights, the wall, and border, would be no more.

The filmmakers get around the impending end of the Cold War by having Bond essentially side with the KGB against a common enemy, something that, again, dates back to The Spy Who Loved Me. This is despite M’s protestations. Bond disobeys a direct order to assassinate the new head of the KGB. This is hardly the first time Bond has allowed his hunches to override orders. It’s not even the first time in this film - he’s already disobeyed the order to kill Kara (“if he fires me I’ll thank him for it”). But it’s the most serious Bond has been about resigning (or being fired) from MI6 since On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, another film featuring a new actor in the Bond role.

While the locations and geopolitical context surrounding Bond are rife with liminality, it’s Dalton’s interpretation of the character which queer audiences might connect with most. It’s no negative criticism to say that Dalton plays Bond more self-consciously than anyone who preceded him. He doesn’t “cut through life” apparently without effort like Connery’s Mr Kiss Kiss Bang Bang and he certainly doesn’t play things in quote marks like Moore. While not indecisive, he does get anxious and riled in a recognisably domestic way. Witness him waiting for Kara as she collects her cello. His agitation is understandable (they’re about to have the KGB and Police force on their tail) but he utterly loses any semblance of Connery/Moore calm-under-pressure cool. A similar moment occurs in the climax, with Dalton clearly mouthing “for f*ck’s sake” as Kara fails to grasp the idea that she should drive her jeep into the back of the moving plane (I’m with Kara on this one - I have no idea how he expects her to ‘get’ such a crazy plan, even with his moderately-decent mime of the desired action)

At times, Bond appears more like a bickering spouse in The Living Daylights, the scenes between him and Kara playing out like an old fashioned sitational comedy. Admittedly, losing your patience with your other half while you wait for them to come out of Homebase on a Sunday afternoon is significantly less perilous than escaping from the Russian army, but the energy is the same.

Dalton’s Bond is The Living Daylights is, dare I say, within our league, romatically-speaking? Although he’s ultimately just as unlikely to settle down as any of the other Bonds, his humanity allows us to play with the fantasy for an hour or two. That’s exactly what Linda does at the end of the pre-titles sequence. She’s had enough of “playboys and tennis pros” (a reaction against the 80s yuppfyfication of masculinity perhaps) and wants a “real man”. This is still an abstraction of course: what does she mean by a “real man”? And when Dalton literally drops into her life I cannot help but think of the Milk Tray Man. For non-British readers: this was a Bond-inspired character appearing in adverts for Cadbury’s chocolates from 1968-2003 (he reappeared briefly in 2016, played by an easy-on-the-eye Liverpuddlian fireman). Each advert consists of the Milk Tray Man performing some elaborate Bond-style derring do (skiing, flying a helicopter, parachuting) just so he can drop off a box of chocolates in a different woman’s bedroom. And then he leaves. The adverts were a staple of British TV and utterly hilarious today, but they cemented the sublimation of sexual activity into women eating chocolate (see also those adverts, contemporaneous with The Living Daylights, in which women performed fellatory acts on Cadbury’s Flakes).

While Bond may not bring Linda chocolates, he does stick around, at least for a couple of hours.

Aside from main girl Kara, Linda is his only conquest. It was widely reported at the time, and confirmed by the filmmakers subsequently, that the AIDS crisis was responsible for Bond being more responsible in the bedroom, eschewing the carefree casual sex of the Moore era. It was still known as the ‘gay plague’ in the vernacular, and in many societies it still carries that connotation today. For instance, right now in the UK, men who are sexually active with other men are still forbidden to donate blood.

So it must have been a principled decision for the filmmakers to reign in Bond’s sex life and set a good example. Perhaps the only alternative was to show Bond putting on condoms. I’m still waiting for that official Durex tie-in. Would sheathing his manhood represent the ultimate loss of Bond’s manhood? The lesser of two evils, perhaps, was showing Bond taking fewer sexual partners.

Was there ever a time in Bond’s history where the filmmakers thought audience might view James Bond as a ‘pansy’ or a ‘poof’? Maybe not, but it does call into question the motivation for having Roger Moore bed so many (mostly) willing women.

Dalton’s self-conscious portrayal marks him out as unique. Self-consciousness is a trait we rarely see in Bond, even with the subsequent tendency to make him more ‘vulnerable’. You don’t have to be queer to be self-conscious of course. But queer people are inherently less certain of their place in the world. We have to write out own stories rather than just adhere to the heteronormative script pre-written for the majority of people follow.

Similarly, Dalton has a script which was not written specifically for him but which he’s determined to make his own. “Bond, James Bond” and “shaken not stirred” are not lingered over, as are none of the one liners. He’s far less self-conscious with the lines that sound right when uttered through a ‘cruel mouth’, particularly those lifted almost wholesale from Fleming (“Plenty of time for a sniper to make strawberry jam out of him.”).

And yet, Dalton is widely considered to be more ‘sensitive’ than any previous Bond (a word often used to euphemistically describe queer people). The rough is balanced out with the smooth. Dalton’s dichotomous performance encourages us to ask: is Bond’s toughness an act? To use a loathsome phrase that often stems from internalised homophobia, is he ‘straight acting’? Or is this the behaviour of a ‘real man’ of 1987?

By today’s standards, some of Bond’s behaviour is reprehensible, particularly towards women (see below). Furthermore, he plays a pretty Machiavellian game, lying to Kara for most of the story. This aspect of Dalton’s Bond is pushed to extremes in Licence To Kill. Here, his coercion of Kara does come across a little creepily at times. The ferris wheel scene is saved from feeling completely sullying by John Barry’s sweet and innocent scoring. Bond using his sex appeal has always been a part of the character. But forming sexual relationships while living under a false persona is generally more frowned upon than in 1953, as the recent Metropolitan Police controversy showed.

Of course, at the time Bond was getting started and well beyond, the only option for many queer people, and criminalised gay men especially, was to have anonymous sex or to use false names. Getting discovered could ruin careers and lives. They had no choice but to be ‘under cover’ most, or all, of the time. No wonder homosexuality and spying were inextricably linked in the public consciousness. As Bond himself says to Q in The Living Daylights: “You don’t find too many normal people in this business.”

Friends of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

When I conducted a Twitter poll asking who would be the best candidate for Bond’s boyfriend, Saunders was a popular choice. It’s not hard to see why. Queer or not, we’ve probably all been a Saunders at some point in our lives: falling for someone who cannot, or will not, love us back.

Bond and Saunders get off on the wrong foot. Saunders’s ire is provoked early on, at their first meeting, when Bond waltzes into his life with his know-it-all setting stuck at maximum. It doesn’t help that Bond is also running late. It’s unclear whether this is because of the extra time he spent with Linda on her yacht or because he’s spent too long dressing for the occasion. Saunders assumes the later, perhaps because of his own internalised homophobia, it not being very masculine to spend hours in front of the mirror.

Saunders is framed very quickly as a civil service pen pusher, a type Bond never gets along with. Furthermore, he seems to know all about Bond: “Forget the ladies for once” he tells him, thinking (correctly) that Bond is mixing business with pleasure. Clearly Bond’s reputation precedes him. So is this personal or professional jealousy? Bond appears to have his eyes on the ladies and not the mission. At this point we don’t know Kara is the sniper. Saunders may be professionally irritated but is he just as annoyed that he’s not the one on the other end of Bond’s gaze? “Forget the ladies for once, Bond".” (Subtext: notice me instead!)

We’ve been there Saunders. We feel your pain.

Saunders’s by-the-bookness doesn’t so much irritate Bond as get completely ignored by him - and then thrown back in his face. The line “Section 26, paragraph 5, need to know. I’m sure you understand” has become shorthand for Bond fans when talking about the need to keep something private. It’s a brilliant character moment for Dalton’s new Bond, showing he knows the regulations - he just doesn’t want to follow them. Saunders’s forlorn expression as Bond drives away, left holding the hefty sniper rifle (see Camp, below), earns him a mixture of ridicule and pathos.

Despite their earlier contretemps, Saunders returns. Surely he could have had a word with HR and had another agent assigned to work with Bond? Is there really only the one MI6 agent in Vienna?

After Bond and Kara have escaped to Austria they go to a concert and Saunders gets Bond’s attention by waving his concert programme at him in a fairly hesitant manner. The question that always springs to my mind is: is Saunders ‘cruising’ Bond?

Since at least the 1600s, gay men have been indicating their interest in each other with secret signals which only gay men knew. How else could they signify their intentions without being uncovered and ostracised? Theatres were famous cruising spaces and their being sexually permissive spaces was one of the reasons they were denounced by prurient members of society in Shakespeare’s time. Although some say the need to go ‘cruising’ has diminished somewhat with the advent of dating apps, it remains prevalent according to others, even in theatres. What often appears in Bond films as spycraft (coded exchanges, flowers in the lapel, etc) could also be read as ‘recognition codes’ of another kind: queers recognising other queers. It’s a very brief moment in the film but it’s interesting that the (somewhat unsubtle) signal appears to have been pre-arranged between Saunders and Bond. Kara is completely oblivious.

Saunders and Bond meet for a third and final time. Saunders chooses the Prater Cafe “near the Ferris wheel”, a location used in a pivotal scene in the 1949 film The Third Man, which has queer connections of its own. The producer of that film, David O’Selznick, couldn’t understand why the main male protagonist was so obsessed with finding his male friend and accused the writers of including too much “buggery” in the screenplay. The screenwriter (and famous novelist) Graham Greene had not included anything of this sort intentionally but, as soon as he was confronted by Selznick, added scenes which amped up the homoeroticism, just to annoy him. Incidentally, The Third Man also features a young Bernard Lee years before he took on the role of M.

By agreeing to go on the Ferris wheel at the same time he’d arranged to meet Saunders (with a rival for his affections no less), Bond comes across as playing more than a little hard to get.

Bond’s treatment of Saunders is particularly unkind because he not only dies in the next scene (see Bury The Gays) but gets dispatched in one of the most (suggestively) horrible ways imaginable - being sliced in half by a pane of sheet glass. Just seconds before, Saunders and Bond had finally made peace with each other, Saunders willing to put his pension on the line for Bond. All he gets in return is a (fairly sincere?) “Thanks” from Bond. Slim pickings. Even so, Saunders’s death galvanises Bond’s actions throughout the rest of the story, in a similar way that Felix’s does in Licence To Kill.

As for Felix himself, he only gets to play the ‘helper’ role in the story. He doesn’t even get to leave his boat. Surrounding himself with attractive female agents is a hypermasculine touch. After Leiter has provided some helpful exposition, Bond declares that they’ve been “working on the same case from opposite ends”. Whatever floats Felix’s boat I suppose! He goes on to suggest he and Felix “talk shop”. The last time we heard this phrase it was Pola Ivanova doing the speaking in A View To A Kill, telling Bond that she didn’t want to talk shop. To be fair, he had just tickled her Tchaikovsky so she probably wasn’t in the mood. We presume - but don’t know for certain - that, with the girls gone above board, Bond and Felix keep things strictly professional down below.

The first time Bond meets the new head of the KGB, General Leonid Pushkin, he pushes him back onto the bed and holds a penis substitute (silenced Walther PPK) in his face.

Need I say more?

Well, Pushkin is presumably named after the famous Russian poet, Aleksandr Pushkin who, although not queer himself, appears to have been an ally. He was quite happy to write to his friend Philip Vigel to recommend men he might fancy I his home town and he concluded one of his to Philip with this (witty?) verse:

To serve you I'll be all too happy

With all my soul, my verse, my prose,

But Vigel, you must spare my rear.

Maybe it sounds funnier in Russian.

General Pushkin, like the poet and unlike the villains (especially Brad Whitaker, see below), is more of a lover than a fighter.

As the proverb goes, the enemy of my enemy is my friend. Although at the time the sight of Bond siding with Afghanistan ‘freedom fighters’ posed few qualms (the Russians were the invaders of Afghanistan at that point after all), it’s a curious sight to see following the so-called ‘war on terror’. Their leader, Kamran Shah, like many people in The Living Daylights, has a mutable identity, being an Oxford-educated Afghan freedom fighter as good with a gun as an ‘theatrical’ performance. He seems to take an interest in Kara (he comes to her concert), although he doesn’t appear to have a ‘hareem’ of women that Bond (somewhat stereotypically!) assumes he will.

Rosika Miklos has ‘worked with’ Bond before and is happy to see him. For his part, he’s happy to see her too. Sexual tension? All we know for certain is she knows a lot about borscht and how to handle a big spanner. As for the borscht, I misheard this when I saw this film for the first time as a child. I thought she was warning Bond about the danger of Koskov being ‘boshed’ rather than ‘borscht’, which sounds a lot kinkier than turning him into beetroot soup.

And as for the spanner? Well, it’s quite a relief to find out that ‘taking care’ of her supervisor does not involve this heavy tool but does involve her taking off her boiler suit and giving him a late shift to remember. To paraphrase Rosika’s own question (a brilliant, subtitled punchline for the character and sequence as a whole), what kind of a woman do we think she is?

She’s pretty unique actually. When a woman appears on screen in Bond wearing unfeminine clothing, my queer coding sensor lights up like a Christmas tree. But I get nothing of that here. Why have I always been so drawn to this character, right from my first viewing of The Living Daylights? Is it because, although apparently heterosexual, she subverts heteronormativity by upsetting the power dynamic? Heteronormative society is, after all, inherently patriarchal. Is heterosexual desire - in particular the ease with which heterosexual men can be manipulated - being played for laughs? Is it because Rosie is played by the absolutely hilarious Julie T. Wallace?

I was delighted when Julie herself shared with me her approach to the character:

“She is a gal that would do anything for love. My own idea was that she had had a one night stand with Bond. It was a good night. That she allowed herself to fall in love. She would go on to do anything for that man. Even risk her own life! Love and sex? What it lets/makes us do!”

That probably explains why I relate to Rosika so much and why she is a favourite character of many other fans. Like Saunders, her love for Bond leads her into a life of danger.

M is his usual inhibited self, chastising Bond - again - about keeping his mind on the mission and not his bratwurst. Saunders already said this to Bond’s face and then put it in a report. Is everyone taking too much interest in Bond’s libido?

A little more tolerant is Moneypenny who light-heartedly interrogates Bond about his interest in Kara. New Moneypenny actress Caroline Bliss is not as well served by the script as she should be. John Glen himself acknowledges this in the autobiography, regretting not giving her a proper introduction. At least Lois Maxwell didn’t fall victim to the trope of giving a very attractive actress glasses to make her appear more geeky and approachable. But Bliss shares the previous Moneypenny’s impatience with 007. When Bond tells her “you are my type” she retorts (so the whole office can hear) “I’ll file that with the other secret information around here”. Touche.

She rather throws water over Bond’s ardour by inviting him over to listen to her Barry Manilow collection. Bond clearly considers Manilow’s music to be a bit ‘naff’ (to use a gay slang term that has entered the vernacular) and we’re expected to share this view. This perceived naffness had nothing to do with his closeted sexuality but everything to do with Bond’s snobbery. Manilow came out publicly as gay thirty years after The Living Daylights, in 2017, revealing he’d been with his male partner for over 40 years. Bless you, Barry. It’s never too late.

Shady characters: villains

Sex and death have always been intertwined. From Greek myth to Shakespeare to Bond, fictional characters have been willing put their lives on the line for love. Rosika (See Allies, above) is willing to risk is all for Bond. How many of us would be willing to risk death for a night of passion with Necros?

Necros is literally death personified. The Greek word ‘nekros’ means corpse or dead body. But what a body!

Some argue that, in real life, love and death are particularly entangled in the lives of gay men - and sometimes women. You can get executed for breaking anti-gay laws in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Chechnya and there are many fates only slightly less worse than death in more than 60 countries where homosexuality is illegal. And before any English people reading this think of casting the first stone it’s worth remembering that men were hanged for homosexual acts as recently as the early 19th Century in our country.

Even in countries where homosexuality is legal, the shame of being outed drives many to suicide. And let’s not forget the AIDS crisis which, although mislabelled as a ‘gay’ illness (see Bond, above), did initially kill disproportionately high numbers of gay men.

If sex and death are so linked in both fiction and real life, it’s curious that one man death machine Necros appears to be coded as asexual, something observed by Dr Lisa Funnell, which is almost always a bad thing in Bond. Necros’s immaculate body is honed so he can always perform his murderous job, not perform in the bedroom.

There’s a sense, though, that he manages to get past people’s (men’s) defences with such apparent ease because he is so attractive. The sequence where he infiltrates the Blayden safe house has him adopt three personae to get the job done: jogger, milkman and doctor. Each time, he convinces another man he’s who he maintains he is. The milkman, soon-to-be-garotted with a Walkman, thinks Necros is a “bloody Yank”. It’s not clear why Necros adopts this persona - why not be a British jogger? Perhaps it’s to put the milkman off guard, giving him something to mull over so he doesn’t hear Necros coming up behind him (although Necros leaving the Walkman playing is a bit of a giveaway).

Similarly, the MI6 agent in the guardhouse sees nothing is wrong. He has the somewhat enviable task of patting down Necros. He does it intimately enough that Necros remarks (in a Cockney accent) “mate, watch it”.

During his attack on the house Necros speaks over the radio in an upper class, Received Pronunciation English accent so the MI6 operatives buy his story that there has been a gas leak.

Later, he disguises himself as a balloon seller in order to hide in plain sight and assassinate Saunders.

A man of many guises, it’s never clear what Necros’s real identity is. When speaking as ‘himself’ with Koskov and Whitaker he has an unspecified Eastern European accent (actor Andreas Wisniewski is German). But his nationality and that of his “comrades” who are fighting for “world revolution” remains intentionally vague (see discussion of geopolitics in Bond, above).

Another mutable character then in a film packed full of them. Whether because of this or because of Necros’s Greek god body, many queer Bond fans I have spoken with find him distractingly appealing to the eye, including Ben Williams and Calvin Dyson. The latter relates how the pool scene, with Necros emerging from the water wearing a tiny blue speedo, was a “finding yourself moment” for several of his gay male friends. Others have observed how they found themselves rewinding their VHS copies and wearing out the tape and or/the pause button. I could not possibly comment but I can present some screen captures for your perusal (you wouldn’t believe the number of times I had to rewind this to get the right images).

As a defector, Georgi Koskov’s mutability is never in dispute. Where does his real allegiance lie? It turns out not to be to any country, or even to another person. Koskov’s only looking out for one person: himself.

Defection, spying and sexuality have been linked in the public mind since at least the middle of the 20th century, when the famous Cambridge Five were unmasked as spying for Russia. Three of the five were queer. Those who defected to Russia included Guy Burgess (gay) and Donald McLean (bisexual).

More recently, research by psychologists into the persistence of homophobia in Western cultures has shown that some heterosexuals may perceive gay men as being “defectors” from the group and this would “motivate aggression towards gay men” in order to “deter free riding”. In other words, scaring them back into falling back in step with the dominant group.

The word ‘defector’ comes from the same Latin root as ‘defective’, the word we use to point out there’s something wrong or faulty.

There are more than enough hints that there is something seriously wrong with Koskov: he gives even Bond a run for his money with his epicurean tendencies. He’s a snob, plain and simple, who will do whatever it takes to live the good life. One of my favourite lines is when he utterly betrays Kara (to her face this time) by attempting to have her shipped off to Siberia. Promising to pull some strings so she can continue to play her music, he acknowledges that the prison orchestra is “quite good, despite their bourgeois repertoire”.

Befitting someone so well-spoken, he has a distaste for verbalising anything violent, preferring to talk about death in euphemistic code (“put away”; “eliminated”; “he’s how you say… history”). Sex and death are linked here again - the two topics guaranteed to get people in ‘polite society’ reaching for the euphemisms, especially if the discussion of sex is non-heteronormative.

So is Koskov politely queer? Is he coded as such?

He’s certainly touchy-feely in a way Bond finds alarming. He greets Bond with a hug. Bond disentangles himself, promising Georgi that there will be time for hugs “later”. But when Bond visits Koskov at the safe house, he’s even more alarmed at Koskov kissing him, although his self-consciousness is probably a result of the other men in the room being witnesses. What if James and Georgi had been alone without the prying eyes of society?

Koskov receives no such hostility from his “old comrade” Colonel Feyador. Traditionally, Russians have been more effusive than stiff upper-lipped Brits, although men kissing other men in public has undoubtedly become less socially acceptable following the fairly recent spike in homophobia, with hatred towards gay people being wielded as a political weapon. As recently as the mid-1990s, the ‘Soviet fraternal kiss’ was a thing, with all men, from the President on down, unafraid to lock lips in public. So when Koskov kisses him, are we to read that Bond is bemused at a cultural difference or fearful that another man is overstepping the mark?

Even after Koskov is unmasked and minutes away from leaving Bond in an Afghanistan jail to rot, Koskov tells Bond he has “great affection” for him, but, as per an ‘old saying’, “duty has no sweethearts”. Bond’s retort leaves Georgi in no doubt that there’s no love lost between them as far as he’s concerned.

Although many have noted how much Bond looks out for himself (Young Bond author Charlie Higson calls him the “ultimate individualist”), Koskov pushes this to villainous extremes. He even arranges for his girlfriend to pose as a sniper knowing that she will almost certainly be killed by Bond! Two birds with one stone? It’s tempting to read queer subtext into this - a gay man using another man to kill off his heteronromative side - but I don’t believe for a minute Koskov has any room in his life for anyone other than himself.

What a git.

Equally as irredeemably odious is arms dealer Brad Whitaker. Besides having a name like a gay porn star, Brad lives in a house crammed with statues of himself dragged up as famous military leaders. For most of the 20th Century it was an idea largely unchallenged in the field of psychoanalysis that while not all narcissists were homosexual, “all homosexuals were by definition narcissists”. The strong association of narcissism and homosexuality played a “major role” in making homosexuality something abnormal to be feared. Despite a more nuanced understanding in psychoanalysis today, homosexuals consistently measure more highly on scales of narcissism than heterosexuals - but lower on self-esteem. The reasons for this are debatable but some suggest that years of having your self-esteem destroyed by a homophobic society could lead you to adopting narcissistic behaviours (such as being exhibitiostically loud and proud) to protest against the norms of society. Who can blame us?

It’s clear that Brad suffers from a lack of self-esteem from the way he talks to Pushkin about the reasons for him being expelled from West Point. We never find out whether he really did cheat on his exams but based on his other childish behaviours it’s a reasonable assumption.

Elizabeth Lunbeck argues that psychoanalysis, taking their cues from Freud, conflated self-love with sexual self-love. Homosexuals, it was claimed were literally in love with their own genitals. This is something everyone goes through, apparently, but heterosexuals grow out of it.

Now, I hate to generalise, but I know quite a few otherwise well-adjusted heterosexual men who have definitely NOT grown out of this either. If you’re a woman and you have empirical evidence to offer, please do so in the comments below.

Certainly, when it comes to Brad Whitaker, if there’s anything he loves as much as himself, it’s phallic objects. Second only to the statues are his other questionable choice of interior decoration: guns of every description, from across the whole history of warfare. He delights in describing the penetrative powers of his latest high-tech acquisitions to the completely disinterested General Pushkin.

Whitaker’s world is entirely phallocentric. We don’t count the girls he gets around to amuse Koskov in his rooftop pool - he’s too busy eating to pay them any attention (a classic sublimation of sexual desire). The only person he seems to have any time for is Sergeant Stagg, a handsome soldier in a tight khaki uniform. It’s Stagg who almost kills Bond before Pushkin arrives in the nick of time to shoot him dead. Was Stagg intending to avenge Whitaker, his superior officer, his employer, his friend (and maybe more)?

I’ve already highlighted the importance of location in The Living Daylights (see Bond, above). But Tangier is especially notable in another way: in the middle of the 20th Century it was a “haven” for gay men from the West escaping sexual censure in their home countries. Gay novelists, playwrights and filmmakers flocked to Morocco, and Tangier in particular, because of the comparatively relaxed attitudes to homosexuality. Even Fleming notes, in the novel of Moonraker, that Tangier is a place where you can “do anything, buy anything, fix anything”.

So why, Brad, do you and Stagg decide to settle in Tangier? Hmmmm. I wonder.

Finally, let’s talk about THAT prison scene. The one where both Bond and Kara are shoved aside by Koskov and left in the care of the prison warder, a thoroughly repellent rapist. As they enter, he announces that “I haven’t had a woman prisoner for a long time”. So you’ve ‘had’ prisoners who weren’t women?

Fortunately, we are saved having to witness the actual gang raping of our heroes by Bond whistling at the guard. Although it’s not the wolf whistle (he saves that for Brad Whitaker), the first bars of Rule Britannia trigger the stun gas in the key ring, just in the nick of time.

The ensuing fight has an akward tension. I believe the filmmakers, probably subsconsciously, are exploting the audience’s fear of being raped by another man.

The potential rapist quickly recovers from the gas (clearly not a “normal” person who should be knocked out for longer, according to Q’s earlier explanation) and forces Bond over a desk, his groin pressed against Bond’s behind. Furthermore, he’s trying to shove Bond’s face onto a phallic object, albeit a very very pointy one. A paper spike seems an odd thing to have on the desk of someone who we presume is too busy raping prisoners to do much in the way of paperwork.

Bond tackles the man by kicking him in the, er, tackle. And then he attacks him with his own weapon and slams a cell door on his arm (a rare shot of blood in a largely bloodless film).

It’s the most violent scene in the whole film. Only the fight in the kitchen at the Blayden safe house comes close. And the object of Bond’s ferocity is not even a significant character. He’s allowed to live, but is clearly in agony. Justice, then, has been served on an odious rapist? But would Bond have been depicted as this violent if only Kara had been threatened with sexual assault? I doubt any of us feel the need to defend Bond’s actions in this scene. He’s acting out of self defence. But there’s something tonally a bit off. Why even include the element of sexual violence? In my mind, the scene exploits the audience’s homophobia and Bond’s violent actions are almost a ‘gay panic’ defence.

You go gurls!

Doesn’t some part of everyone want to be Kara Milovy? Don’t we all want to be whisked away from humdrum reality (her apartment is grotesque, even before it’s ransacked by the KGB) into a new life of adventure?

Well, frankly, no. Not if we have to go through what Kara goes through in The Living Daylights.

You have to feel sorry for her. First she is used as a stooge by her boyfriend, told to pose as a Soviet sniper, oblivious that this will probably get her killed (god knows what Koskov told her was going to happen!). As a result, she is used as target practice by Bond. Then she is interrogated by the KGB. And that’s before she is seduced by this strange man who is posing as a friend of her boyfriend. Although Bond is gentlemanly enough to book a second bedroom in Vienna, it’s not long before he’s paying off a fairground operator so he can take her for a “ride” at the top of a big wheel.

When she finds out Bond has been lying to her, she drugs his Martini. Kara love, you are utterly forgiven: that’s the least I’d do to him if I was in your position.

And yet, she manages to rise above all of this and really comes into her own in the film’s final section. While Bond is fiddling about with the plane, she’s commandeering a jeep and driving after him, almost running over her (now ex) boyfriend, Koskov. When Koskov realises who is driving, it’s the ultimate betrayal and John Barry scores it brilliantly: a bold version of the title theme kicks in just after Koskov says “Kara!” and continues as she puts the pedal to the metal.

Kara is resilient. That’s probably why a lot of queer people can relate to her.

The original story had Kara actually being a KGB sniper. It’s an intriguing idea that would have changed the story wholesale. The more egalitarian nature of the Soviet intelligence services is alluded to as Q goes through the records of known female assassins, including one who kills people with her thighs, the progenitor of the idea for the sexually ‘abnormal’ Xenia Onatopp in GoldenEye.

Although there’s nothing queer about her, I feel duty bound to mention Pushkin’s poor mistress. Not only is she stripped naked by Bond to act as a distraction (okay, maybe that does say something interesting about Bond’s sexuality), but she has to witness her man being violently assassinated only for him to spring back to life minutes later - a plan Pushkin was complicit with!

You can do so, so much better my dear.

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

The girls over the opening titles have found some clothes. Was this some more AIDS-era prudery or recognition that maybe it wasn’t acceptable to make the opening montage the equivalent of ‘reading’ page 3 of a tabloid newspaper?

The Living Daylights has the requisite quotient of gorgeous background girls. One of my favourite shots is during Bond’s escape from the police after ‘assassinating’ Pushkin. He skirts the edge of a courtyard which is full of girls whose single occupation appears to be sitting around looking pretty and waiting for superspies to briefly break the monotony of the day by running over your roof. Nice work if you can get it I suppose.

As well as the girls, The Living Daylights has a plethora of pretty boys in small or non-speaking roles. In the spirit of redressing the balance after 14 films of straight men ogling women, here is my unapologetic gay male objectification of three bit part players:

The soldier who shoots Bond with paintballs and tells him “You’re dead!”, which is definitely a different sort of chat up line. He’s actually played by stunt coordinator Paul Weston.

Also appearing in the pre-titles sequence is Michel Julienne, son of driving stunt maestro Remy and a stunt driver himself. He had more screentime behind the wheel in For Your Eyes Only’s 2CV chase and appears here (looking equally eye-catching, although blink and you’ll miss him) with a (weirdly dead-eyed) wife and child in the car. Not gay then? Never mind.

No wonder Q’s having trouble breathing when he gets up those stairs to see Koskov off in the plane - I would be too if there was a cutie like that waiting for me. If I worked at MI6, I may even feign the odd asthma attack when he was around the office.

The Aston Martin Vantage is one of my favourite Bond vehicles with some seriously camp ‘optional extras’ installed. The laser cutters in the hub caps are a camp(er) update of Goldfinger’s tyre-shredders and whenever I buy a new car I hope it comes with a head up display and missile launchers. I’m not so fussed about the retractable skis.

Bond leaves Saunders holding a seriously BIG gun (see Allies, above). The production designers actually added lots of extra scopes to make it look like THE BUSINESS. Who knows what this most self-conscious of Bonds is supposed to be over-compensating for? It’s largeness makes the gag of Bond leaving it with Saunders to dispose of even funnier. There’s another gag I could write about Saunders having to unload and pack away Bond’s big gun but this is a serious, academic piece and I would never stoop so low.

Speaking of stooping, there is an abnormally high volume of toilets in this film. Even by Bond movie standards, it’s excessive. Most notably, Koskov escapes his KGB minders by sneaking through a window in the gents’ bathroom. Later, Bond investigates Kara’s cello case in a lavatory cubicle. He receives a lot of furtive glances from the other lavatory occupants and gives some of his own in return. It was once thought taboo to even show a toilet on screen (Hitchcock did it in Psycho to shock the audience). Such homosocial spaces are useful in spy stories - people tend to be a bit firtive and mind their own business in a water closet - but they are also places where heteronormative masculinity is “defined, tested and policed” (see my GoldenEye re-view for a detailed exploration of this). Other spaces in The Living Daylights where they don’t even have to bother with a ‘no women allowed’ sign include the airbase with its prison (see Villains, above) and shower block, which is demolished with a JCB, exposing the naked men inside.

Bond helps Koskov defect by shoving him inside a pipeline. This is a family-friendly site so I’m not going to launch into a detail description of what, in gay slang, is sometimes called ‘piping’. All I’ll say is, Google with caution. Definitely NSFW.

I love it when composers cameo in the films they are scoring, even it’s the very definition of a camp, wall-breaking gesture for those in the know. It’s entirely fitting that John Barry appears at the end of The Living Daylights, his final Bond score. Although interestingly he’s not conducting his own music but the finale to the Rococo Variations by Tchaikovsky, the famous Russian composer who struggled with his homosexuality for many years but then made (relative) peace with it.

Queer verdict: 005 (out of a possible 007)

A queer energy permeates The Living Daylights and drives its story. As the title song says ‘A hundred thousand changes / Everything’s the same’. The film embodies this apparent contradiction, most of all in its main character, played by a new actor. Whoever he’s been played by, Bond has always been a locus for liminality: he leads a double life; he’s cultured but a blunt instrument capable of extreme violence; he’s the ‘ultimate man’ with feminine traits. But Dalton’s performance helps The Living Daylights vaciliate between each set of extremes, preparing us for the transition to the ‘darker’, ‘harder’ and ‘more serious’ Bond of Licence To Kill. The 1987 world that 007 inhabits is just as amorphous, with allegiances and identities constantly shifting. Who is an ally? Who is a villain? Who - out of Saunders, Rosika, Koskov and Kara - is most in love with Bond? Perhaps they could share?