Queer re-view: For Your Eyes Only

Bond has gravitas (and gravity) again after the out of this world adventure of Moonraker. But being back down to Earth doesn’t mean we have to jettison the camp and the queer completely. And Margaret Thatcher gets chatted up by a parrot. Take that Section 28!

If this is your first time reading a re-view on LicenceToQueer.com I recommend you read this first.

‘Inspired by For Your Eyes Only’ by Herring & Haggis

“The name’s Bond, Flaming Bond?”

For Your Eyes Only is the Bond film equivalent of the day after the night before, albeit quite late in the day, when the worst of the hangover has passed. The night before was, of course, Moonraker, the epitome of Bond excess (until Die Another Day at least).

Although it definitely has its moments, For Your Eyes Only is one of the least camp Bond films and it invites us to take Roger Moore’s Bond more seriously, ‘seriously’ being a relative term: we’re still in the outrageous fantasy world of Bond after all.

Seriousness and sincerity are traditionally seen as the antitheses of camp. Camp, of course, is not a pre-requisite for something to be ‘queer’, even if, in many people’s minds, camp and queer appear to be inextricably intertwined.

As Susan Sontag put it back in the 1960s:

Not all homosexuals have Camp taste. But homosexuals, by and large, constitute the vanguard—and the most articulate audience—of Camp.

And yet, some of the most queer works of art of all time are also the most sincere, subverting heteronormativity in the most serious ways imaginable. I contend that some of the ‘hardest’ Bond films are also some of the queerest (particularly Licence To Kill and Casino Royale). Conversely, some of the campier entries overcompensate by giving Bond a seemingly never-ending series of female conquests (we’re looking at you again Moonraker).

For Your Eyes Only begins with a clear statement of intent, telling the audience we’re at the very sincere end of the Bond spectrum. In the world of Bond, there is probably no more sobering sight than seeing him visit his wife’s grave. Aside from a brief reference in The Spy Who Loved Me, Bond’s widower status hasn’t featured since Tracy died in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. It hovers in the wings for the early part of Diamonds Are Forever before being told to go home and not bother coming in for the rest of the run. A similar stunt is pulled here, although there is even less of a link between Tracy and her erstwhile murderer because Blofeld can’t be named (see villains, below).

Reminding the audience Bond has a dead wife is a quick way to instantly inject some gravitas into proceedings, although we never dwell on it for long. As is well established by now, for all the Bond films’ ostensible heteronormativity, the economics of franchise film production determine that Bond can’t be in a long-term relationship. And if there are two women on the scene, one must be sidelined or sacrificed so he can settle (for a few minutes at least) into a monogamous groove in the final scene. In some films, this leads to Bond’s connections (‘relationships’ perhaps being too strong a word) with women feeling utterly trivial.

I have no doubt that Bond’s love ‘em and leave ‘em approach appealed to a me as a young gay kid who couldn’t picture himself being happy in a relationship with a woman, or a relationship of any kind. How many gay men grew up thinking love ‘em and leave ‘em was their only option?

But deep down, because I’m a fingers-at-the-back-of-the-throat sickening romantic, I still held out the hope that one day my hero would find true love - with anyone - because I wanted that as well. In a perverse way, having a tragically deceased wife seemed like the best of both worlds. He had tasted true love but lost it and had sort of moved on, but he would always pine for what he had and couldn’t have again.

If that all sounds very mixed up, welcome to my brain from around 1988 until 2008!

While in real life a state of disequilibrium lasting for twenty years leads to considerable unhappiness, in the safe comfy confines of a two hour Bond film, it’s the ultimate pleasure. We want our hero to suffer so that he earns his happy ending. This isn’t something exclusive to queer Bond fans. Wanting a character to have their happiness snatched away before it is restored again is innate in all human beings in all cultures across the globe. We find this narrative trajectory relatable, even inspiring. It appeals to our sense that, however bad things get for us, we can find our way out. A happy character, in a constant state of equilibrium is boring. The end credits can’t arrive soon enough.

Starting off For Your Eyes Only with a visit to Tracy’s grave instantly sets up this disequilibrium. Last time we saw Bond he was orbiting the Earth in a space shuttle having sex in zero gravity. Tracy’s restores the gravity, grounding us in the most literal way possible by making us think of Bond’s unhappiness, buried six feet under. It’s the filmic equivalent of announcing “I’ll never drink again” after a stupefying night of Bacchanalian excess.

And then a helicopter arrives. Hair of the dog?

The first five minutes of any film are instrumental in setting-up its tone and getting the audience to buy into the world the film inhabits. This is doubly true of a Bond film where the pre-titles sequence often acts as a microcosmic representation of the full adventure that will follow.

For Your Eyes Only’s pre-titles sequence sets us up for a film of extreme contrasts, switching from a grave-side visit in bucolic Surrey to a villain’s elaborate attempt to dispatch Bond with a remote-controlled helicopter over a very unglamorous gas works. It comes to a close with Bond cold bloodedly dropping the villain down a chimney complete with Looney Toons-style sound effects.

A lot of fans describe the film as one of the ‘harder’ Bond films. When I think of For Your Eyes Only the first scene that always springs to mind is Roger Moore kicking Locque’s car off the side of a cliff. It’s a Connery-esque moment that Moore himself struggled with. But the second scene I think of is the Citreon 2CV chase which is up there with the best, and funniest, action sequences in any Bond film. The third involves Margaret Thatcher, but I’ll get to her later.

Moore’s performance is considerably more sincere in For Your Eyes Only than in any of his previous four adventures. He actually makes Bond recognisably human for the first time in a long while. Directing the first of his five Bond films, John Glen makes it clear that, under his watch, Bond will always show genuine concern for the death of his allies (see Ferrara below) and seek to understand the motivations of the girls and help them accomplish their goals, rather than merely ride roughshod over their desires and bend them to his will to accomplish his mission.

Does Bond’s sincerity mean that For Your Eyes Only is less camp? Yes, for the most part. Contrast-y it maybe be, but even the outlandish elements are rooted in a framework which is less in quote marks than Moore’s preceding four films.

Friends of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

Is there any Bond film with more of a daddy fetish than this one? (According to my husband who is more attuned to these sorts of things, the answer is an emphatic: NO)

And yet, this is the only film where the daddy of them all, M, is absent. Of course, in real life, Bernard Lee had died just as production began. The filmmakers felt wary of filling his shoes with indecent haste so used the character Bill Tanner (played by James Villiers) to fill his place, in the process making the character less of Bond’s pal and more of his crotchety, ill-at-ease superior.

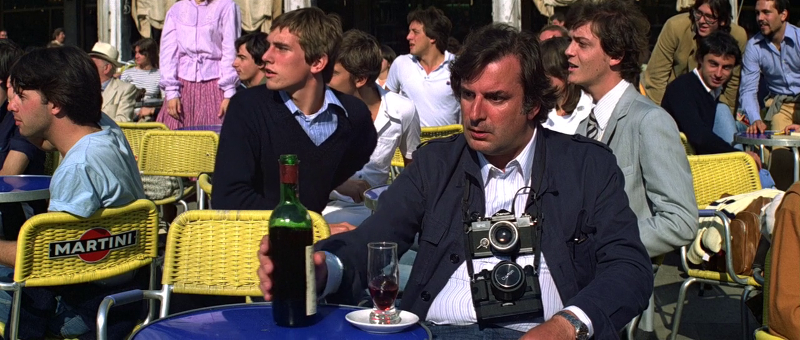

Fortunately, Fiddler On The Roof star Topol is here to fill the (paternal? fraternal?) bonhomous void as Columbo, a devastatingly handsome (again, according to my husband) figure who occupies a Kerim Bey/Marc-Ange Draco helper role, whose day-to-day pursuits are vaguely illicit.

Moneypenny’s filing cabinet gadget is utterly ludicrous and, as a result, utterly brilliant. And Bond seems to have no problem with giving flowers to a man, although “as M’s away” he bestows the bloom on Moneypenny instead.

Minister of Defence Frederick Grey (played again by EON stalwart Geoffrey Keen) is cowering at the thought of delivering disappointing news to the Prime Minister. One might launch into a diatribe about insecure men feeling threatened by female authority but his trepidation is somewhat understandable when one realises that the PM in question is none other than the unequivocally villainous Margaret Thatcher (see Villains below).

General Gogol’s workplace romance is not even a secret anymore. One of the chief pleasures of the Roger Moore era is seeing Gogol embrace his feelings (and, by extension, more libertarian western ideology). This is the point where he crosses the divide between villain and ally. He even prevents his bodyguard from killing Bond in the finale. In Bond’s words: “That’s detente comrade”. Gogol chuckles. See you in Octopussy General.

Q goes on a mission in full disguise for the first time, something director Glen actively encourages across his tenure. His orthodox religious censure of Bond’s sexual behaviour is true to form. A real highlight of this film for me though is the sequence where Bond and Q spend hours using the identigraph machine to identify Locque. It encapsulates the mixed tone of the film as a whole: Bond is doing some serious spy work (even if the technology is hilariously dated) while being brought cups of coffee by Q’s impossibly glamorous assistant Sharon. The scene ends with Q telling Sharon “I’ll lock up”, which makes Q’s lab sound like a high street shop. It’s just about the most down-to-earth thing anyone has ever said in any Bond film.

Shady characters: Villains

We should know Aris Kristatos is a wrong ‘un when he orders wine that is “too scented” for Bond’s palate. Is this the same Bond brand of snobbery that unmasks Grant in From Russia With Love when he drinks red wine with fish? Or is it Bond’s fragile hypermasculinity under threat from something vaguely feminine once again? Probably both.

Kristatos is played by British acting legend Julian Glover, who has a track record of playing urbane villains, usually with clipped British tones (especially clipped as General Veers in The Empire Strikes Back). His antagonist in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is cultured but ultimately a sheep in wolf’s clothing in the manner of Kristatos. Of course, this being a Bond film he must be othered with a foreign accent (Greek). Unlike a lot of Bond villains who are coded as asexual or homosexual, Kristatos appears to be straightforwardly heterosexual (if you count sponsoring a barely-legal ice skater so you can get into her bed as straightforward).

The unnamed bald-headed villain played by John Hollis (another The Empire Strikes Back alumnus) in the opening titles is clearly intended to be Blofeld but left unmonikered because of the dispute with rival filmmaker Kevin McClory. He’s more in the visual mould of Telly Savalas (complete with neck brace) than the most recent Blofeld, Charles Gray, whose delectably camp performance elevated Diamonds Are Forever to camptastic heights. Perhaps it’s fortunate Gray didn’t return for Blofeld’s last encounter with Bond - there’s only so many times you can ‘bury the gays’ after all.

I’m not alone in finding Emilio Leopold Locque a queer figure. Queer Bond fan and film graduate Jack Bell thinks Locque is subtly queer-coded, highlighting how “smooth and urbane he is”. Locque never says anything to identify him as queer. In fact, he doesn’t say anything at all. But he has an intriguing look. For a start, he’s blonde, which has been a queer code from at least far back as the Victorian era (Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, for instance). And Blondeness often carries feminine connotations in the world of Bond. When Daniel Craig was cast as the first ‘Blonde Bond’ he was vilified by many before he’d even stepped foot on the set.

Perhaps Locque’s queerest scene is when he’s delivering the money for the hit on the Havelocks. He appears ill at ease sitting around the pool in his suit, the poolside festooned with scantily clad girls. He watches on calmly, dispassionately as Melina and Bond’s actions cause chaos and ruin the party. As he exits, he snatches back a wodge of cash, almost spitefully, from the girl who was tossed the money by the assertively hetero assassin Hector Gonzales.

Another blonde, the biathlon champion cum KGB operative Erich Kriegler, flaunts his hairless, oiled, muscular physique (if you’ve got it, why not?). According to Bibi Dahl (who finds him “dreamy”) Kriegler lives an ascetic lifestyle, akin to the departed monks of St Cyril’s. Apparently, “he won’t even talk to girls”. He’s a less taciturn Hans from You Only Live Twice, although Krieglier is not exactly verbose. He’s not a million miles away from Necros in The Living Daylights, although he doesn’t share his predilection for disguises. He’s also a less sadomasochistic Stamper from Tomorrow Never Dies. Like these other blonde henchmen, he spends a lot of time in the gym (a modern recent code).

Another silent (though less muscled) blonde is henchman Claus, played by Charles Dance. Director John Glen recalls Dance not being happy at being given direction to hold his gun straight, although he was probably more aggrieved that his only line of dialogue was cut. A few years later, Dance appeared on TV saying Glen had told him not to hold his gun like a “poof”. This was at a time when producers were looking to replace Roger Moore with a new Bond. Glen brushed off the remark and was still considering Dance, but Cubby Broccoli refused to consider him, perhaps out of a feeling of disloyalty.

I agonised for a long time (okay, a few seconds) about placing Margaret Thatcher in the villain category. It’s unseemly to speak ill of the dead after all. And while it would be a gross oversimplification to paint Margaret Thatcher as the sole ‘author of all my pain’, it would hardly be a misstep on the scale of Spectre retconning Blofeld as the villain all along.

The simple fact is that Margaret Thatcher led the government that introduced Section 28, the legislation that made it illegal for public sector institutions to ‘promote’ homosexuality. Effectively, this meant that from 1988 until 2003, teachers (or anyone paid by the government) could not say it was okay to be anything other than straight. That meant, unless they had a voice of reason in their own family, a whole generation of queer kids grew up internalising their feelings and hating themselves. As someone whose formal education lasted throughout most of this period, I was smack bang in the middle of ground zero. As an educator today, I spend a sizeable chunk of my time dealing with the fallout and hold Thatcher and her government directly responsible for ruining the lives of thousands of queer people, some of whom never recovered from their feelings of shame.

Who knows how far along we might be with LGBT rights nowadays if this huge stumbling block hadn’t been placed in the way? Goldfinger’s grand plan only involved irradiating gold. Thatcher’s plot was far more insidious: she destroyed millions of lives from within.

She is a villain, plain and simple.

So I make no apologies for taking great delight at the lampooning of Margaret Thatcher at the end of For Your Eyes Only. She is portrayed uncannily by Janet Brown, alongside John Wells as husband Denis. Robbie Sims (of The bubbles tickle my Tchaikovsky fame and author of Quantum of SIlliness) also has the utmost respect for Janet Brown’s performance while acknowledging it has “some serious drag queen energy”. Fans of Ru Paul’s Drag Race would laud Brown’s take on the character as a ‘Snatch Game’ performance extraordinaire.

It’s a minor compensation for a ruined childhood that I can take a childish glee in watching Margaret Thatcher get chatted up by a parrot, but it always makes me smile.

You go gurls!

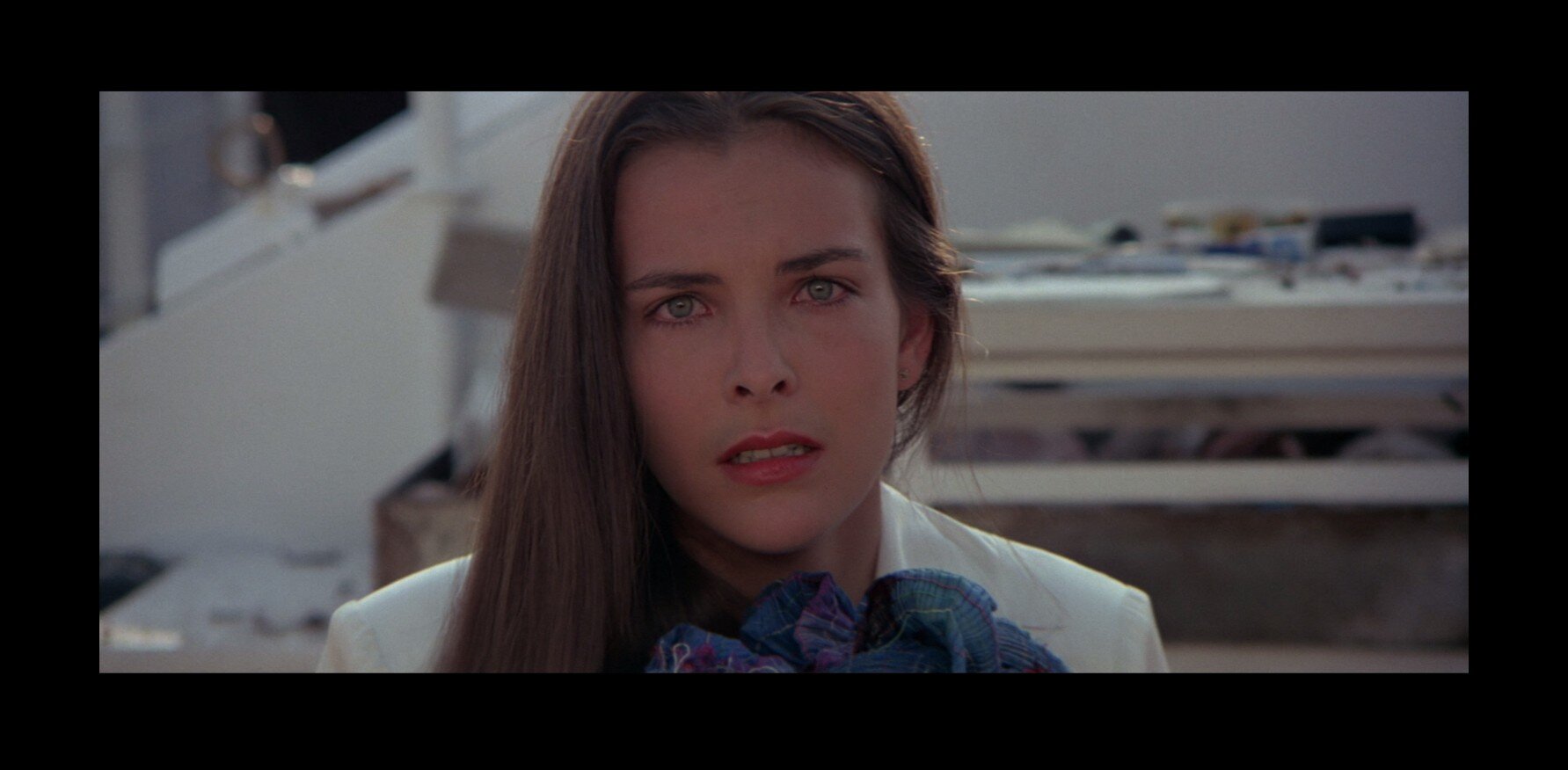

Most Bond girls don’t get to have their own stories - or if they do, they only get to tell them once they meet Bond for the first time. Not only do we get Melina Havelock’s tragic backstory shown on screen well before bumping into Bond (and almost bumping him off), but she actively pursues her own agenda for much of the film’s running time. She also gets to keep most of her agency, crossbowing people into the final act. That she doesn’t get to perform the coup de grace on the villain (unlike Domino in Thunderball) is justifiable, in my view, completing her arc satisfactorily. Although one gets the feeling she could have easily executed Kristatos in the nick of time (saving Bond’s life) if Columbo hadn’t beaten her to it first!

Melina is a favourite of several queer Bond fans, including trans woman Spencie d’Entremont, who finds Melina an inspiration and has recreated the iconic poster pose on her Instagram (complete with crossbow of course).

Another queer fan says: “I always thought the character of Melina would be great portrayed as a fierce, kick ass LGBTQ woman” and questions whether it is essential for Bond and Melina to have sex at the end, echoing my own sentiments. Bond and Melina hooking up always seems a little perfunctory to me.

It would take another 27 years, with Quantum of Solace, for the filmmakers to end an adventure with Bond not ‘getting the girl’. One wonders whether, with a little more courage, they may have attempted to do the same with For Your Eyes Only.

According to a 1983 interview with screenwriter Richard Maibaum:

The whole idea was that the great lover James Bond can't get to first base with this woman because she was so obsessed with avenging her parents' death. Nothing was ever done with it. It was as if the director didn't feel there was a love story there at all.

While this idea is still present in the film subtextually, I am quite relieved that John Glen did not follow through as fully as Maibaum intended. Bond overcoming the resistance of an ‘ice queen’ has been a staple of the franchise since Goldfinger, with coded lesbian Pussy Galore “immune” to Bond’s charms. It’s a discomfiting trope to say the least.

As she appears in the finished film, Melina is presented more as Bond’s equal. In addition to her crossbow skills and knowledge of underwater diving, she’s as good a driver as Bond and the filmmakers make sure we know it. Every time a sexist joke about women drivers looks to be forming on Bond’s lips she shows him how capable she is at getting them out of a tight spot, and in a bright yellow Citroen 2CV no less.

Even if the romance feels somewhat forced in the middle act sleigh ride, it’s arguably necessary to act as a symbolic consummation of sorts. It allows us (and Bond and Melina) to focus more on the mission at hand, although in Melina’s case that means returning to her parents’ boat and waiting around a bit. A curiously out-of-place (and easy to miss) shot in the casino reveals that Melina (in an bright red dress) is fully aware that Bond leaves with Countess Lisl and she doesn’t look too happy about it. In the finished film it’s not revealed how she feels about this, although a deleted scene on the DVD/Blu Ray shows her challenging Bond about his “sex life”. Director John Glen says it was deleted because it “took away” from her character, perhaps because it would make her more traditionally heteronormative, condemning Bond for his polyamorosity.

I suspect Melina almost disappears from the film in the middle act because the audience would not be so open-minded. More conservatively-minded viewers would only accept Bond having sex with another woman when the main love interest is hundreds of miles away.

In this case, the other woman is the he utterly charming, very femme but - as it turns out - not fatale Countess Lisl. She herself as trustworthy by not being foreign at all, but really coming from a northern English town (shades of Ruby Bartlett from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service). Her death hits Bond hard and we feel it too, thanks to some superb editing and stunt work. The stuntperson involved in the scene (Cyd Child) was injured in the visceral crash through the buggy windscreen and it’s easy to see why on screen.

Bibi Dahl makes Bond look like a prude. And that is her main function, narratively-speaking. She helps to ground Bond, putting him into a heteronormative-shaped box by comparison. Bond fatherly (grandfatherly?) “I’ll buy you an ice cream” eliminates any possibility that he is about to embark on May to December romance. This helps to make Kristatos more villainous when he is unmasked, his intentions towards Bibi being less honourable than Bond’s.

Bibi’s trainer Jacoba Brink is arguably coded as queer. There are no obvious instances of her crossing the personal-professional line with her young mentee and she appears, if anything, motherly towards her. But there is something truly venomous about Kristatos’s claim that “you have done this, poisoned her [Bibi] against me”. It smacks of sexual jealousy. For a film which bears some story similarities with From Russia With Love, there’s definitely a space for a lesbian character. Fortunately, Jacoba Brink is far more sympathetically portrayed than Rosa Klebb!

Although her name does not appear on the credits and she only appears on screen for a few seconds as ‘Girl at Pool’, Caroline Cossey is well known as, and happy to call herself, a ‘transsexual Bond girl’. Less happily, she was the subject of a pernicious hounding by the journalist Bill Rankine from News of The World, who outed her as the ‘Bond Girl Who Was a Boy’ the year after For Your Eyes Only’s release. Not only was this unnecessarily cruel (whose interest did the story serve?) but it was inaccurate. Technically, Cossey has XXXY chromosomes, not the traditionally female XX or male XY. Nevertheless, she was designated a boy at birth and given the name Barry. She had to endure years of prejudice and heartache until she could be her true self.

Despite her family doing everything they could to protect her, the tabloids broke the story, framing it in a way that made it appear she had deceived the Bond producers.

Even under her modelling/stage name Tula, Cossey had been turning down high-profile assignments so she could stay off the tabloids’ radar. She knew she would be running a risk by appearing in a Bond film, with all its associated publicity.

By her own account, her two weeks on the set of For Your Eyes Only were happy ones. As one of the eight Bond girls of (in Cossey’s own words) “all nationalities, colours, shapes and sizes” she fit in well with Roger Moore and everyone else on set. Director John Glen recalls (in his 2001 memoir) spending a lot of time dancing with Caroline at a discotheque. He describes her as “stunning” looking and recalls being shocked to learn afterwards that she “had been born a boy”. In the next paragraph he goes on to give details of “a more serious casting mishap”, implying that Caroline’s casting was also a mishap. Had the filmmakers known that Caroline was trans would they have cast her?

When the News of the World story broke after the film’s release, Caroline thought her career might be over - not just in film and TV but as a model. She contemplated suicide but came out the other side, campaigning for the rights of transgender people everywhere.

There are several good online accounts of Cossey’s career and her own book (she published her autobiography My Story in 1991) is well worth reading in full. In the book, she is proud of her Bond appearance but downplays her part as that of a “glorified extra” used to “decorate the set”. And yet, her impact on the trans community and public perceptions of trans people cannot be downplayed. Recently, archive material of her in the Netflix documentary Disclosure introduced a new audience how strong, resilient and witty she is. What could be more quintessentially ‘Bond girl’ than that?

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

The title song promises that “you’ll see what no one else can see”, which presumably is not a mere allusion to the contents of a manila folder. Singer Sheena Easton pops up herself in the somewhat fourth-wall breaking but otherwise quite subdued, calming opening titles (the obligatory girl sliding down the barrel of the gun aside).

Three years later, Easton would release Sugar Walls, written by Prince, which pushed the same idea as For Your Eyes Only to suggestive extremes:

Let me take you somewhere you've never been

I can show you things you've never seen

I can make you never want to fall in love again

Come spend the night inside my sugar walls

Unsurprisingly, Sugar Walls has since become a camp classic.

The Bill Conti music score to For Your Eyes Only reflects the peculiarly hybrid tone of the film. I’ll be honest: I struggled with this soundtrack as a teenager getting into film music. I thought the influence of contemporary music undermined the excitement of the ski chase in particular. I’ve grown to love every single note of it though. It becomes more Barry-like in the final act but I really look forward to certain sequences because of their scoring (A Drive In The Country in particular). My highlight is the really watery electronic version of the Bond theme that accompanies our first viewing of the Neptune submarine cutting through the depths. It’s so on-the-nose and quite wonderful.

Conti also wrote the song that plays in the pool scene, Make It Last All Night, the lyrics for which are so obscene I can’t even bring myself to type them out.

The zoom in to Melina’s eyes as she discovers her parents’ corpses and vows Electra-like revenge is like something out of a 70s Hong Kong action movie (NB: This is not a compliment, not a criticism).

The first seven notes from the chorus of Nobody Does It Better accompany the pressing of the keys which unlock the huge room containing Q’s identigraph machine.

Victor Tourjansky completes his character arc, making his final (and briefest) appearance as the man being caused to question his alcohol intake because of 007’s antics ruining his holidays. In The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker he has to check the ABV of whole bottles of red wine as Bond drives out the sea in a Lotus Esprit/out of the Venice lagoon in an inflatable gondola. It says a lot about For Your Eyes Only as a whole that the antics here are comparatively sane: Bond skis through an outdoor seating area followed by some less graceful motorbikes. Commensurate with the film’s more sober approach, Victor is seen drinking more responsibly. He is credited as ‘man with wine glass’, although if he’d continued on to appear in Octopussy I’m sure he’d have been back with the whole bottle.

Queer verdict: 003 (out of a possible 007)

There’s a lot here that’s queer, even if its not as loud and proud as some of the other entries. It definitely holds up to a re-viewing through queer lenses if you know what you’re looking for. In the words of the title song: “you can see so much in me, so much in me that’s new”.

Thank you to everyone who has helped shaped my thinking about For Your Eyes Only for this piece. In addition to those credited in the piece itself, thanks to Phil Whitfield for researching the name of the stuntwoman who performed as Countess Lisl.

And if, by some miracle, Caroline Cossey ever reads this: I am in awe of you and your journey. Thank you for risking your career - and a lot more besides - to appear in For Your Eyes Only.