Queer re-view: Die Another Day

Non-binariness is baked into the very DNA of Die Another Day and not even experimental gene therapy can alter that. Although there are binaries aplenty - a dual mission, fire and ice, a duelling dual showdown over a divided country - the film rejects any earnest attempt to pin it down as one thing or another. Fear contends with desire in a cockfight to the death. Analyse this.

If this is your first time reading a re-view on LicenceToQueer.com I recommend you read this first.

This article is also available as a podcast, wherever you get podcasts (links in the top left of the header, above).

‘Inspired by Die Another Day’ by Herring & Haggis

It’s easy to dump on Die Another Day. It appears - with the tedious inevitability of an unloved movie - at the bottom of fans’ rankings, including my own for a time. But the truth is, it takes less effort to pick a side. It's easier to write off an entire film than to try weighing its handful of questionable creative choices against its admirable qualities. Binary thinking is socially desirable. We seek approval by taking a strong stance one way or the other and finding a tribe of people who agree with us - and another group (‘them’) who vehemently oppose us. Binary thinking is also instinctive and is a monster which takes effort to overcome.

While Licence To Queer has never been the place to ‘review’ the Bond films in the sense of saying some are better or worse than others, it’s impossible to analyse Die Another Day from a queer point of view without exploring some of its commonly - and less commonly - cited flaws.

The name’s Bond… Flaming Bond

Like the recipient of a deeply-suspect DNA transplant, Die Another Day is an attempt to blend new and emerging trends in culture and filmmaking with the feel of a classic Bond film. Not only that, it’s also narratively-speaking, both a Rebirth and Overcoming the Monster tale, two distinct archetypal story styles. The resulting experience is an identity crisis unfurling, sometimes jarringly, in front of our eyes. And the film’s identity crisis is mirrored, to an extent, in the character of Bond.

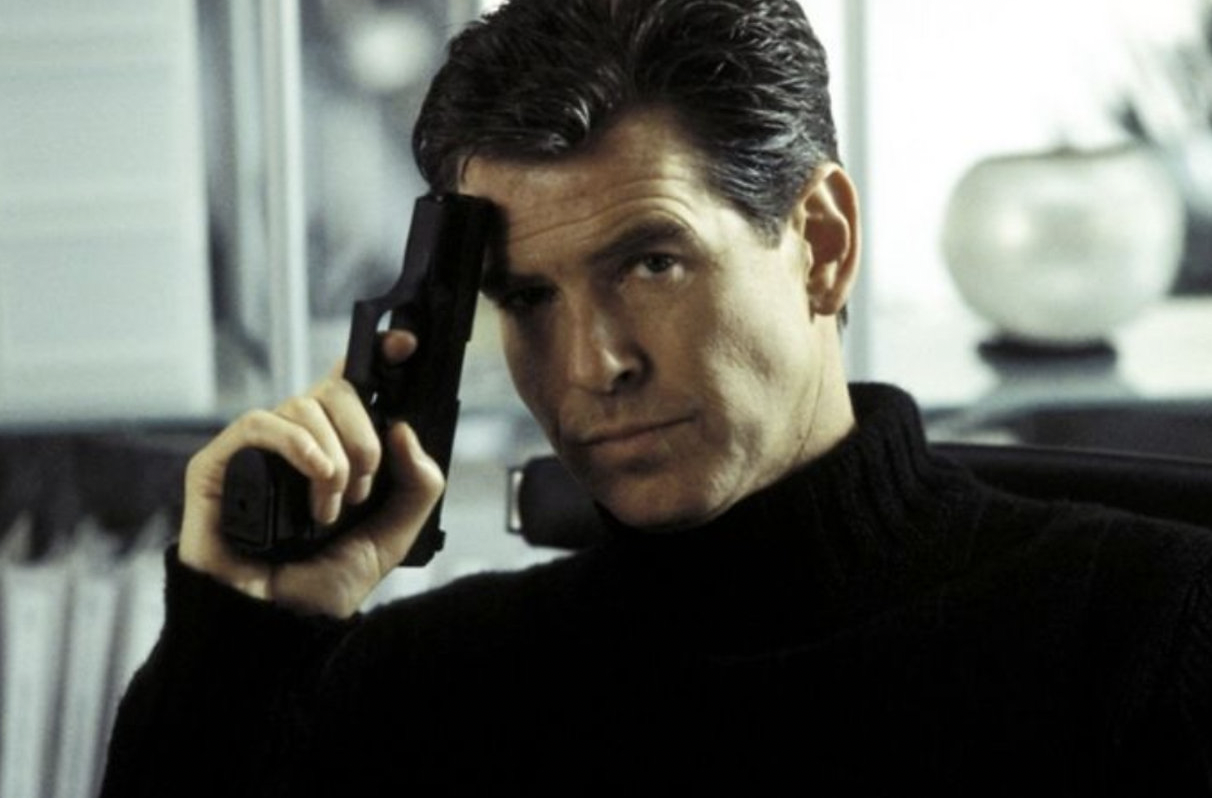

When you watch the behind the scenes material for Die Another Day, it quickly dawns on you that key crew members were setting out, to begin with at least, to make the closest thing possible to a Cold War-era thriller. Brosnan himself said, during filming, that Die Another Day was shaping up to be "a reality-based character-driven piece".

While it would be easy to scoff at this now, it is possible to see the film through this prism. True, you need to strain your eyesight a bit. But while many fans are prepared to look away from the less ‘reality-based’ aspects of films like From Russia With Love, For Your Eyes Only and Licence To Kill, they are less inclined to do so with Die Another Day. Sometimes, that's all they focus on.

Perhaps this is because Die Another Day doesn't conceal its working. Its juxtapositions are more like contradictions. It's fitting that a fire and ice motif runs - not entirely smoothly - through it. When fire and ice meet, chances are you will either end up with an extinguished flame or with a puddle on the floor. They clash rather than complement each other. And although the ‘heat’ of the inevitable coupling of Bond and Jinx at the end might incline us to think fire has won the day, it’s not that clear cut.

Die Another Day being a damp squib in many people’s eyes comes down to it being neither one thing or another, but multiple things simultaneously - and these oppositions are not always resolved. For a beginning, it starts off as one type of story and ends as another.

One of the most influential examinations of the stories human beings find most satisfying is Christopher Booker’s 2004 book The Seven Basic Plots, in which he uses copious examples - including several Bond stories - to illustrate his argument that, across the whole of human history, there are only seven stories. All stories are versions of these seven archetypal structures: Overcoming the Monster, Rags to Riches, The Quest, Voyage and Return, Comedy, Tragedy and Rebirth. According to Brooker, all of Fleming’s Bond stories fall into the Overcoming the Monster category. In this story type, the hero (Bond) is called upon (by M) to defeat a monster (Le Chiffre, Mr Big, Hugo Drax, Blofeld, et al.), overcoming deadly ordeals in order to (quoting Booker) “end his adventure locked in fond embrace with the liberated ‘Princess’”.

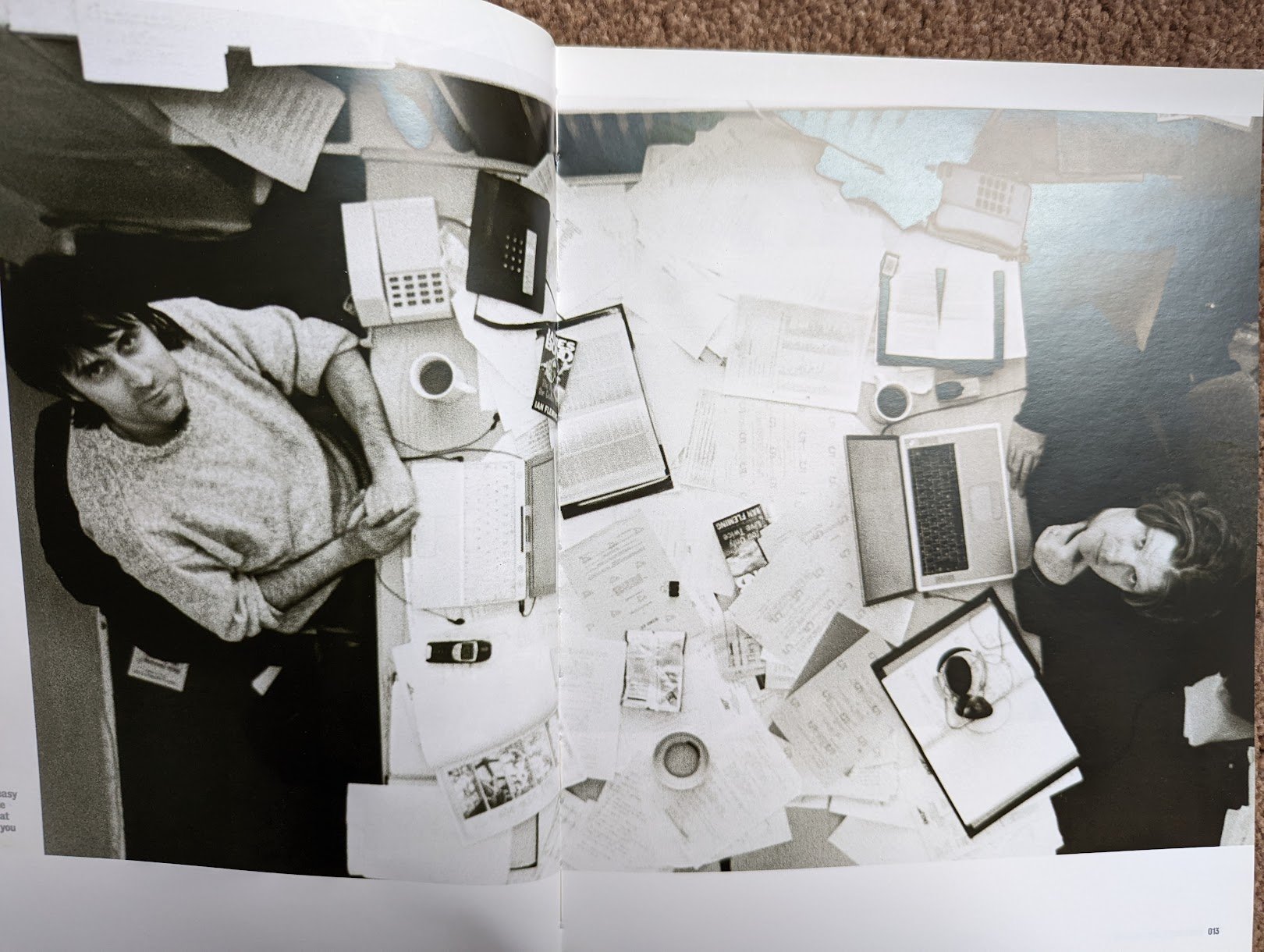

Even Fleming’s You Only Live Twice, which Booker acknowledges as being “darker than any of the Bond stories which preceded it”, is an Overcoming the Monster story. I bring this up because in production photos of Die Another Day the writers are seen with a copy of this book face up on their writing desk, indicating - unlikely as it might first appear - that they drew on it for this film.

In this novel “a strange new element” intrudes on the Overcoming the Monster structure: Bond acquiring the identity of a Japanese fisherman threatens to break the Bond mould. You Only Live Twice almost becomes a Rebirth story. It only doesn’t Brooker says, because “Bond has not really discovered his identity. He may have acted out the external pattern or a rebirth, but he has not been through any inwards transformation. He has merely covered up his old identity with an outward disguise”.

This critique of You Only Live Twice appears in the second half of Booker’s book, where he dissects stories which don’t fit nearly into his seven boxes and are, therefore, in Booker’s view, less satisfying. When I read his book for the first time not long after its initial publication, I found it utterly compelling to begin with before becoming increasingly irked by it. (Something it has in common with Die Another Day?) Naively, I believed my irritation with The Seven Basic Plots stemmed from my own reluctance to concede that its author might have nailed it in one: the stories which the majority of human beings find satisfying are heteronormative, and that included my beloved Bond stories.

Booker writes:

“One of the key reasons for the success of the Bond stories… was precisely the way they tapped unerringly into those springs of the human imagination which had given rise to similar stories for thousands of years. So accurately did the typical Bond novel follow the age-old archetypal pattern that it might almost serve as a model for any Overcoming the Monster story.”

As a gay man, reading passages such as this gave me an overwhelming feeling of swimming against the tide of “thousands of years” of human stories springing from “the [collective] human imagination”. To be satisfying to its audience, an Overcoming the Monster story had to end with the rescue of a Princess? Overcoming the Monster, along with the six other ‘basic plots’ essentially gave us the map we use to live our lives? Was it therefore, millennia before I was born, pre-determined that I would live an unsatisfying life?

While Booker was undoubtedly an erudite and learned man, it came as a massive relief to learn he was not right about everything. He was a climate change denier for one, and held somewhat controversial views about passive smoking and asbestos: Booker claimed that neither were injurious to one’s health. We can therefore take some of his sweeping assertions with a healthy degree of skepticism.

Although he made a living out of controversy (espousing his discordant views in his column for The Telegraph) he does observe in The Seven Basic Plots that “When we see two people locked in bitter dispute, almost invariably neither is wholly right. Each may be partly right and partly wrong… yet it is only too natural to us to oversimplify.”

Is this what is going on when people express polarising views about a James Bond film? While you can argue that it’s a facile debate about something which is essentially trivial, is it really? Are we not really talking about something deeper? When we say we love one film and hate another aren’t we really saying we value some stories more than others because their structures mirror how we live our own lives? The stories we love validate who we are and the choices we make. The stories we hate help us to define and shape who we aren’t.

The need for queer people to ‘come out’ in most societies means many queer people are drawn to Rebirth stories in particular. It’s common to hear gay, lesbian and bisexual people talk of their lives beginning in earnest after they came out. There’s a reason many trans people refer to the names they went by prior to their transition as their ‘dead name’.

Rebirth tales are not incompatible with Overcoming the Monster stories: there is still a threat to be overcome, but this time it’s more of a dark power, usually something less tangible. This power threatens to overwhelm them until they undergo a momentous transformation. While Rebirth stories we encounter in childhood (such as fairytales) frame the ‘dark power’ as an supernatural-imbued external threat (a witch, an evil wizard, a ghost), in adult Rebirth stories characters are threatened (Booker says) “by the dark part of themselves”. The key ingredient of a Rebirth story is the literal or metaphorical death of the protagonist which precedes their literal or metaphorical second life beginning. In Die Another Day, Bond dies literally AND figuratively. After stopping his own heart to escape from his MI6 prison he thanks the nurse who revives him for the “kiss of life”. But he’s still under the dark power of being an outcast who is, in the words of M, “no good to anyone”. M takes a more enlightened view when Bond returns from Cuba but he’s still under the dark power to a degree for the rest of the story.

Die Another Day begins as a Rebirth story and segues into an Overcoming the Monster story, the threat shifting from inside Bond himself to the more external, tangible threat of Gustav Graves, with the Rebirth story continuing to run alongside in the background. It’s a queer structure for a Bond film.

Interviewed by Matthew Field and Ajay Chowdhury in 2015, screenwriter Neal Purvis said that a story idea for the film which appealed to him was “Bond, captured at the beginning of the story, spends the rest of the film trying to get home” but concluded that “that isn’t a Bond movie”. Had Purvis been encouraged to persevere with the idea, we would have had a Rebirth story from start to finish. It would not have been the first time that Bond was the black sheep left out of the MI6 fold (Bond goes as far as leaving the Service in Licence To Kill) but it would have been very different from the Die Another Day we got.

As we watch the film, if we’re not prepared to mentally make the switch from Rebirth to Overcoming the Monster ourselves, we experience dissonance. Our brains expect the Rebirth story set up in the first act to continue in the foreground throughout the second and third acts, but it doesn’t. It’s a strange paradox that a Bond film which is probably better served by turning off your brain requires you to make a mental effort to get the most out of it.

The filmmakers appear to be aware of the bumpiness of the transition. The plane Bond is travelling on (signalling the beginning of the film’s second act) experiences turbulence prior to landing in London. Bond wryly tells the cabin crew member “Lucky I asked for it shaken”. The audience watching this very shaken film may not be quite so accepting.

Does this mean that queer people, who are perhaps more experienced at making significant changes part way through their lives, are preprogrammed to look on Die Another Day more favourably? Hardly. When I asked Licence To Queer readers what they thought of Die Another Day, my twitter poll (with 300+ votes) revealed queer and non-queer people like/loathe the film in roughly equal measure. I take from this that none of us like a sudden left turn in our lives, even though some of us have little, if any, choice in the matter.

The Clash

To a varying degree, all Bond films are clashing mixtures of things that shouldn’t work together. Die Another Day has so many clashes (and even The Clash at one point) that nothing ever quite coalesces. The result is that we don’t ever truly relax into the film. We are always slightly on edge.

Die Another Day is not only a mix of different story types, but also time periods. It’s neither new, nor old, but both. Nonbinariness again. You might say the same for all Bond films: they are all products of their times with one foot in the present and one in the past. But Die Another Day takes new-oldness to extremes.

Back in 2002, I didn’t think it was very Bondian to have 007 arrive in the film on a surfboard. But somewhat hypocritically, I had never found it troubling watching Roger Moore skimming across an icy pond in the pre-titles of A View To A Kill. I suspect time has a lot to do with this: I first saw Moore’s stunt double trying out snowboarding when I was only eight years old, whereas I was a more cynical adult when I saw a world class surfer standing in for Pierce Brosnan at the beginning of Die Another Day.

Throughout Brosnan’s tenure as Bond, extreme sports had been growing in popularity. ‘X Sports’ were first broadcast by ESPN as an alternative to the Olympics the year GoldenEye was released. But so swiftly had activities like bungee jumping become mainstream that more was required for Die Another Day: riding giant waves (of the real and CGI varieties) was therefore the order of the day. Is surfing, then, a Bond thing or not? It’s both. The sequence feels both old and new at the same time: Bondian and not-Bondian.

There’s a similarly non-binary new-old noncomformity to the look of the film. Voguish experiments in photography and editing, particularly The Matrix’s ‘bullet-time’ approach to showing off its Hong Kong cinema inspired action, led to Die Another Day’s editor Christian Wagner (who had worked with Hong Kong legend John Woo) using not just an unconventional amount of slow-motion but also speed-ramping (during the car chase in particular). But if you were willing to be contrary, you could argue this was an update of Peter Hunt’s approach: from Dr. No onwards, Hunt removed frames to speed up the action, whereas Wagner pressed fast forward through them. The same idea, updated. Newoldness.

For anyone whose enjoyment of Die Another Day depends on their ability to suspend disbelief, the notoriously conspicuous CGI elements - the invisible car and the Bond surfing on an ice wave - finally tip them over the edge. For many, it’s Jinx’s CGI-assisted backwards dive off an impossibly high ledge that marks the point where Die Another Day ‘jumps the shark’.

No one set out to make a film that frequently looks ‘fake’: it’s both endearing and cringe-inducing to hear (on the Inside Die Another Day DVD supplement from 2003) the deadly-earnest visual effects team explaining that it took them over a year to create the ice wave sequence. When the head of the effects team declares that the ice wave looks completely realistic as a result of their considerable labours she clutches her necklace nervously, hoping everyone else agrees.

Break the cycle

A more significant break with Bond tradition is our hero being captured and held prisoner for over a year. He may be “saved by the bell” but he does not save himself.

The events of the pre-title sequence set Bond off on a dual mission:

Find out who outed him in North Korea

Become himself again after having his identity stripped from him

The mission proper begins when he takes a Rebirthing baptismal bath from the deck of a British naval vessel into the Hong Kong Harbour, which had only recently been re-aquired by the Chinese at the time of the film’s release. With its literal and political comings and goings, Hong Kong harbour is a liminal space if ever there was one - a fitting place for a character’s Rebirth.

It’s not a true Rebirth yet however. The subsequent scenes on terra firma attempt to convince us that Bond can be rebuilt the way he was with some well-chosen accoutrements: Bollinger Champagne, freshly-pressed tailored shirts, a sexual proposition from a woman who is obviously a honeytrap and quickly revealed as such.

But wait… The last time this happened (From Russia With Love) Bond didn’t realise he was being filmed from behind the mirror.

Something is off.

The callbacks to Bond films from the preceding 40 years, peppered throughout Die Another Day, seek to reaffirm what we think we know about the character. But the cumulative effect is to put some distance between us and Bond. They highlight the artifice of him and his world.

When Bond’s well-aimed ashtray shatters the two-way mirror it reveals a camera crew. Look, the film is telling us: you’re watching a movie! There are cameras everywhere - you just can’t see them! The illusion is shattered along with the mirror.

If we’re prepared to go with it, it makes us call into question everything we think we know about Bond and the ensuing Cuba sequence shoves this in our faces. Bond hasn’t smoked a cigar in years, but why not? When in Havana! A floral shirt? Okay then! And while we’re about it, why order a Martini when you can order a Mojito?

A Cuba sequence in a subsequent Bond adventure, No Time To Die, has a similarly nonconformist feel. While it lasts, it hints at an expansion to the character’s possibilities before the Overcoming the Monster formula inevitably starts snapping back into place, beginning with Bond’s return to MI6.

“You never thought of looking inside your own organisation?”

Bond’s betrayal from within parallels the experiences of queer people in the real life spying profession, many of who have suffered a great deal at the hands of their supposed allies. The ban on LGBT people serving openly in MI6 was not lifted until 1991 and, according to one gay former spy, the fear of being outed persisted into the beginning of the 21st Century, when Die Another Day is set. And the consequences of being outed were severe. A queer former spy interviewed in 2021 (remaining anonymous for more than the usual reasons perhaps) said:

"I was outed to security department by colleagues while on my first posting, then put on the next flight home and told to expect dismissal. I was allowed to stay, but the price was heavy: a list of family and friends I was forced to come out to; a pink tag attached to my personnel file, and years of resentment and fear.

"Throughout the 90s, there were direct discriminatory impacts on families and partners, allowances, pensions, promotion, career management and postings.”

30 years after the ban, in 2021, current ‘M’ Richard Moore publicly apologised on behalf of his organisation for the way LGBT+ colleagues were treated, stating the vetting bar had been "wrong, unjust and discriminatory". This followed earlier apologies from the heads of GCHQ in 2016 and MI5 in 2020.

The irony is that several of the most high-powered spies in British history have been queer. This includes the seventh real life M, Sir Maurice Oldfield, who was in charge of MI6 from 1973-1978 and continued to work in intelligence at the Prime Minister’s behest after retiring. He had his intelligence career shortened by being outed as gay by those supposedly on the same side. In 1980, a report into his homosexual activities from rival organisation MI5 led to him having his security clearance withdrawn. Until then, he was in charge of co-ordinating British Intelligence forces in Northern Ireland. He died the following year. In 1987, he was publicly outed as gay by The Sunday Times who had been fed the information by a right-wing faction within MI5.

Queer spies, even those at the top, lived, in the words of the former spy interviewed above, a “precarious” existence. Until very recently, queer spies were viewed as a security risk and, if caught, would be interrogated and almost certainly expelled from the service.

We get a flavour of that from the opening act of Die Another Day. After Bond is traded back to MI6, he is interrogated again and made to understand, in no uncertain terms by M, that his getting caught out has rendered him useless.

Bond: The same person who set me up then has just set me up again to get Zao out. So I'm going after him.

M: The only place you're going is our evaluation centre in the Falklands. Double-0 status rescinded.

Bond: Along with my freedom?

M: For as long as I deem necessary, yes.

Out of the frying pan (North Korean military jail), into the fire (MI6 house arrest).

Even after Bond’s return from Cuba, it’s not a hero’s welcome; he remains disavowed. A deleted scene shows Bond evading immigration checks at London Heathrow by hanging on to his plane’s landing gear. Even without this scene, it’s clear that he’s M’s dirty little secret whose work on this mission will remain off the books. He re-enters MI6 through the back door, as it were. Specifically, he unlocks (using M’s calling card - a giant key) an innocuous looking door on Westminster Bridge and descends beneath the pavements to an abandoned Tube station.

London (Underground) Calling

Gay historian Peter Akroyd uses the analogy of London as a human body, referring to the capital’s pavements as the skin of the city. The underworld below - with its miles and miles of tunnels and passages - is “like the nerves of the human body” because “it controls the life of the system”. To Ackroyd, London’s underworld is “a place of fear and of danger, it can also be regarded as a place of safety. It is both “malignant” and “a place of fantasy… where the ordinary conditions of living are turned upside down.”

The dialogue between Bond and M reflects the duality of London’s underground spaces:

Bond: I heard of this place. Never thought I'd find myself here.

M: Some things are best kept underground.

Bond: Abandoned station for abandoned agents.

They need to talk about Gustav Graves but can only do so away from prying ears. But they also need to talk about Bond himself:

M: So, what have you got on Graves?

Bond: You burn me and now you want my help?

M: What did you expect, an apology?

Bond knows he’s an outcast. M doesn’t correct Bond’s assertion that he’s an abandoned agent. The message is clear: he will have to prove himself to regain his previous status. M is certainly not going to say sorry.

London’s underground spaces have been synonymous with disgrace for centuries. An earlier chronicler, writer, historian and theatre impresario John Hollingshead, wrote this in 1861:

“Even now, in these days of new police and information for the people, it would not be difficult to find many thousands who look upon them as secret caverns full of metropolitan banditti. When the shades of evening fall upon the City, mysterious whispered “Open sesames” are heard in imagination near the trap door side entrances, and many London Hassaracs or Abdallahs [characters in a stage version of popular play The Forty Thieves], in laced boots and velveteen jackets, seem to sink through the pavement into the arms of their faithful comrades.”

Bond may not be wearing laced boots and a velveteen jacket (soooo 19th century, although making something of a comeback now), but he is impeccably turned out and he does use a secret door to access his comrades - M and Q.

How much of what Hollingshead was writing about was true? In Hollingshead’s theatrical endeavours, he became infamous for putting raunchy content on his stages, including - two decades after he wrote the passage above - The Forty Thieves, an Arabian Nights piece. A romanticisation of London’s underworld reality Hollingshead’s depiction may have been, but he was reflecting the public perception of his time. He acknowledged this:

“Imagination generally loves to run wild about underground London… a popular notion exists that those few sloping tunnels are a vast free lodging-house for hundreds of night wanderers; and that to those who have the watchword they form a passage leading to some riotous hidden haunt of vice.”

Evidence that there ever was a “hidden haunt of vice” is appreciably hard to come; it’s not as if anyone wanted to leave any incriminating proof behind. But it’s highly likely that queer people would have sought refuge - and each other - during times when relations between people of the same sex were prohibited. The role of underground public conveniences as meeting hotspots (cottages) for gay men is reasonably well documented, mostly because many men were caught and convincted of the ‘crimes’ they committed, or were attempting to commit while down there, beneath the pavements. Maybe those in other underground spaces just didn’t get caught.

When Hollingshead was writing, the London Underground railway where Bond meets M did not yet exist, but it was in its planning stages. He even includes a chapter in his book about it, arguing that although its being built will result in massive upheaval, including the demolition of many houses, it is necessary to relieve the congestion and pollution on London’s streets. It may have also offered relief of a different kind, for queer people at least.

Gay cruising has been going on for as long as gay men have had to find creative ways to meet potential partners and dating apps have not diminished its popularity. A 2020 poll on ‘The world’s largest listing of gay cruising areas’ put the Underground top of London’s list for places to meet men. They recommended the last carriage on any train as the best spot for meeting people. If data were available from a hundred years ago, would we find similar?

And it’s not just sexual assignations that draw queer people to the Tube. According to sociologist Dr Nina Wakeford, the symbiotic relationship between the Tube and the queer community is complex. With a massive disproportion of Underground employees and enthusiasts identifying as queer, the appeal of the Tube for LGBTQ+ people is not in dispute, although the reasons for it are. She explored these for her book, Our Pink Depot.

Although we don’t see an Underground train in a Bond film until 2012’s Skyfall (another anniversary film showing off the Best Of London) this is the first Bond film to feature a scene in an Underground station, even if it is an abandoned ‘ghost station’.

At the very least, the underground scenes show Bond (and other characters) occupying a space which is liminal, a place where nothing is fixed, and therefore inviting of queer readings. While the fictional Vauxhall Cross was once a busy place with passengers using it to transit elsewhere, it’s now changed its function. Its name suggests it is beneath the MI6 headquarters, located on the southern bank of the Thames at Vauxhall. Perhaps coincidentally - or not - the area is also host to London’s oldest surviving gay venue, the Royal Vauxhall Tavern. The Tavern has been frequented by gay men since at least the end of the Second World War, its popularity buoyed by demobbed servicemen. The MI6 building, which was finished in 1994, is clearly visible from the Tavern’s front door. All that lies between the Grade II listed cabaret venue and the headquarters of Military Intelligence 6 is, fittingly, a tunnel. Some things are best kept underground?

“So you live to die another day”

Writer Robert Wade is credited with coming up with the title, a very Fleming-sounding idiomatic phrase that actually derives from a poem by the gay poet A E Housman. The poem containing the film’s title appears near the end of Housman’s collection entitled A Shropshire Lad.

THE DAY OF BATTLE

"Far I hear the bugle blow

To call me where I would not go,

And the guns begin the song,

'Soldier, fly or stay for long.'“

"Comrade, if to turn and fly

Made a soldier never die,

Fly I would, for who would not?

'Tis sure no pleasure to be shot."

"But since the man that runs away

Lives to die another day,

And cowards' funerals, when they come

Are not wept so well at home."

"Therefore, though the best is bad,

Stand and do the best my lad;

Stand and fight and see your slain,

And take the bullet in your brain."

It’s a philosophical argument, weighing up dying young (and possibly gloriously) or delaying the inevitable by running away from combat. Although it’s Bond who tells Graves “So you live to die another day” it’s just as relevant to Bond himself. Both men have lived two lives.

Intentionally or not, this reflects the double life of the poet A E Housman. Knowing he was gay from an early age, Housman appears to have fallen truly in love just the once: with his best mate. Inconveniently, his best mate - a hunky rower he met at university and later lived with - was straight. When his deeply-held feelings were not reciprocated, Housman shut down his emotional life. He channelled his frustrations into his poetry, including some of those included in the collection which supplies Die Another Day with its title.

In the 30th poem of A Shropshire Lad, he writes about the agony of forbidden sexual attraction:

Others, I am not the first,

Have willed more mischief than they durst:

If in the breathless night I too

Shiver now, 'tis nothing new.

More than I, if truth were told,

Have stood and sweated hot and cold,

And through their reins in ice and fire

Fear contended with desire.

Throughout the poem, Housman uses the elemental battle between “ice and fire” to portray his internal battle with his feelings, imagery which also brings drama to Die Another Day’s title sequence. It’s probably a coincidence rather than someone on the production being keen on bringing a bit more than Housman’s title into proceedings. Either way, it’s an effective visual metaphor for the tug of war between fear (ice) and desire (fire) depicted in Die Another Day’s titles and throughout the film as a whole.

When Housman died, he left all his personal papers - which were very open about his same sex attraction - for his brother to make public. Housman’s brother did as he wished and even penned an introduction to them in which he stated his personal and social reasons for allowing the papers to be read by all. Personally, he wanted his late brother to be fully understood, homosexuality and all. Socially, he hoped it would help make people more accepting of gay people. His moving words, with their passion and barely contained anger, are worth quoting in full:

“In their treatment of the homosexual problem, ‘the precious balms of the righteous’ have broken many heads, and many hearts, and ruined many lives. I have a hope that, twenty-five years hence, their day of evil power will be gone; and that society may, at long last, have acquired sufficient commonsense to treat the problem less unintelligently, less cruelly, more scientifically. And if not, it may help to that end for the world to be given knowledge that one to whom it is deeply in debt for the beauty of his poetry and the eminence of his scholarship, was one of the sufferers whom it has in the past found it so foolishly easy to despise and to condemn.”

Twenty five years later, the British Museum opened the packet given to them by Housman’s brother. Uncannily, this was almost the same day that homosexuality was partly decriminalised in England. Housman was posthumously outed, with his consent, just 16 days before the Sexual Offences Act (1967) came into force.

Friend’s of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

Verity doesn’t like cockfights, which is a pretty clear indication of her preferences beyond the sporting arena. Although her speech is full of innuendoes that give Bond a run for his money (‘I see you handle your weapon well.”), there’s not much reading between the lines required. She describes her protege, Miranda Frost, as “gorgeous” and asks Bond what he thinks of her. It’s a pretty positive representation of a lesbian character: Bond and Verity appear to have a cordial relationship going back some time. One can easily imagine them sharing confidences with each other - and perhaps expressing their mutual appreciation for women they both find attractive.

The philosopher Jacques Lacan once controversially claimed “woman does not exist” because she does not have a phallus, the source of all meaning for all of mankind. He meant a symbolic phallus, rather than a literal penis, but he perhaps gave away a bit too much when he asserted that “woman’s sexual organ is of no interest”. This understandably poses something of a problem for lesbians, such as philosopher Judith Butler. While there are some feminists who claim ditching the phallus entirely is the way to go (Criado-Perez, 2014), Butler calls for women to queer the idea, creating a “lesbian phallus”. Is this what Verity is doing, in an almost literal sense, by being so adept with blades, a domain typically dominated by men?

Is fencing a gay sport? Lesbian-centric platform Autostraddle think so. In a tongue-in-cheek list of ‘The Sports That Made You Gay’ they ranked fencing at 13 out of a total of 28 sports.

A possible historical precedent for Verity is the late 17th Century/early 18th Century swordswoman Julie D’Aubingy who had no compunctions about clashing swords with men, wearing male and andrognynous clothing and taking both men and women to her bed. D’Aubingy also had a highly successful career as an opera singer. While Madonna is yet to tackle opera, the actor is such a high profile star that you can’t divorce what you know about her from her character of Verity as you watch her in Die Another Day. What drew Madonna to the role of a lesbian swordswoman? On the one hand, she has been accused of queer-baiting or playing up to the lesbian fantasies of straight men. The year after Die Another Day she courted controversy by kissing Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera at the MTV Video Music Awards and, in 2021, she was criticised by some after she drew a comparison between her on stage same sex kissing and that of openly gay artist Lil Nas X. But many gay men are keen to observe that, right from the start of her career, Madonna has sought to raise awareness of gay issues and has campaigned very publicly for gay rights. Wherever you stand on the debate, you can’t argue that she is a gay icon.

Madonna’s iconic look includes a ‘croc gilet’, made not of real crocodile but made to look like it. One of the creators of the piece, Patrick Whitaker himself, told me it was crocodile embossed vegetable tan leather. Along with his partner in art and life since 1985, Keir Malem, Whitaker created several pieces for Die Another Day. On the From Tailors With Love podcast, Whitaker described himself as a “closet Bond fan” and was an early member of the James Bond Fan Club, so it was a dream come true to be on the set when Madonna was shooting her scenes with Pierce Brosnan.

Does Madonna’s fetching fencing gilet take us into the realm of fetish? Several of the film reviewers at the time seemed to think so (notably, it has to be said, the more prudish critics).

When Nini Barbakadze interviewed Whitaker Malem for Metal magazine, Barbakadze commented that:

“Traditionally, leather clothing — Whitaker Malem's signature material — is considered to be liminal, between the zones of culture and nature… The more leather is thought to embody this liminal factor, the more it can be fetishised. However, Whitaker and Malem's work is more exploratory than fetishistic.”

When I asked Patrick Whitaker if he considered it to be fetish, he told me: “I don’t know if I would consider it fetish gear mainly because we presented it as fashion in the first place. It was in Elle magazine years and years before she got to wear it in the film. Some people would consider it fetish gear because they just do think anything which is black and leather is like that. Of course, it does have that about it. I guess it’s up to the individual to decide.”

The newly promoted Q (latterly, R), has been cooped up in the Underground for quite some time - and all that entails (see discussion of the Underground in Bond, above). Perhaps it’s not surprising that he’s been trying to perfect gadgets which hide in plain sight. This includes the Aston Martin Vanquish/Vanish and a glass-breaking device which is worn on the finger traditionally reserved for wedding rings, as acknowledged in Q’s dialogue.

“One pane, unbreakable glass. One standard issue ring finger. Twist, so. Voila.”

Is Bond supplanting a wedding ring in favour of a gadget confirmation of his ‘confirmed bachelor’ status? ‘Confirmed bachelor’ was an offensive euphemism for a gay man throughout the 20th Century and it survives in some contexts up the present day. Men who avowed their single status were viewed with suspicion. Is it any wonder than so many decided to get married to women to shake off accusations of homosexuality?

From a purely story-telling perspective, it makes sense for Bond to wear the sonic agitator on his ring finger. Social codes concerning men’s dress would make wearing the ring on any other finger conspicuous. It’s still not considered ‘normal’ for most men to wear jewellery beyond a wristwatch and a ring on the third finger of the left hand. Wearing a ring on your thumb is a popular queer signifier, particularly if you’re a woman. According to queer writer Daisy Jones, who has noticed a tendency for fictional and well as queer women to wear thumb rings:

“Thumb rings haven't always been a fashion item. In fact, for a long time, they were intended as protection attire for archers, so their thumb pads didn't get worn down by the bow string. Their history, then, lies in practicality… So it should come as no surprise that, in more recent years, the thumb ring has been widely adopted by lesbians and queer women. I'm actually wearing a thumb ring right now.”

To what extent has marriage equality challenged the social conventions of ring wearing? Is it too soon to tell?

Although there is some evidence that same sex marriages have existed in many civilisations throughout history in some capacity, they have only had legal parity with marriages between men and women very recently. In 2001, the Netherlands became the first country in the world to certify a marriage between two people of the same sex. Belgium and two Canadian provinces would follow in 2003, with the UK lagging behind until 2014 and all states of the USA the year afterwards. Therefore, when Die Another Day was released in 2002, there were no conventions really, beyond those borrowed from heterosexual couplings.

In 2012, ‘gay and lesbian wedding pioneer’ Kathyrn Hamm (founder of gayweddings.com) summarised the state of things:

“In the early aughts and prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage… some chose to use the ring finger (next to the pinky) on the right hand for the engagement and/or wedding ring because of its resonance with, but difference from, the traditional heterosexual symbolism. Others, however, embraced the traditional practice of using the ring finger of the left hand. Some preferred to use other fingers or symbols, like the same (non-ring) finger, while others matched rings but selected different fingers altogether. Because LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered) couples have had no road map for our ceremonies in the past, we have been able to choose the symbols most meaningful to our relationships.”

Where you decide to put your ring carries a lot of meaning. By making the ring fit Bond’s ring finger (for which he must have been sized-up beforehand) has Q weaponised Bond’s bachelorhood, complete with its homosexual associations?

It’s not just M and Q who head underground for their queer activities. Moneypenny heads down there for a virtual reality tryst with 007. While this scene is controversial for some, I have always viewed it as a fitting climax (as it were) to Moneypenny’s narrative trajectory in her Samantha Bond incarnation. In GoldenEye, she made sure Bond knew in no uncertain terms that she doesn’t wait up for him. In Tomorrow Never Dies she is complicit in having him pimp (pump) himself out for Queen and Country, without a hint of jealousy. The World Is Not Enough shows her rejecting Bond’s phallus substitute (cigar) because she has no need of it. All the time, we sense the attraction is mutual between the two of them but Moneypenny would never want to get entangled with Bond’s train wreck of an emotional life. Die Another Day allows Moneypenny to have her cake and eat it: Bond provides the inspiration for her solo sex session without him realising it. There are some who view the scene as problematic for its apparent lack of consent because Bond does not know his image is being used in this way. But how is that any different to someone finding inspiration in a photograph of someone they are attracted to, or in their imagination? The scene is incredibly prescient: VR pornography did not exist in 2002 but it does now.

I see it as an emancipatory moment for Moneypenny, especially because female masturbation is still not frequently depicted on screen. Journalist and author Lucy Jones, writing in The Independent:

“In 2020, it still feels unusual and notable to watch a scene of female masturbation on screen that isn’t included to provide erotic interest for a character and audience. It feels radical, still, to see female autoerotic pleasure without the requisite lingerie, candles and soft-core aspect. Autoerotic pleasure, then, as experienced by the majority of women.”

When Moneypenny is shown enjoying some time to herself, she does so fully clothed in her workwear. It’s a quietly revolutionary moment for any film and especially a Bond film, which often makes a mockery of solo sex. Yes, the scene is included for its comedic qualities, but it does not demean Moneypenny, at least in my eyes, even if it is juxtaposed with the ‘real sex’ (implied intercourse) of Bond and Jinx in the next scene.

Simply put, Bond films - or at least the character of Bond - don’t see masturbation as ‘real sex’. Masturbation is usually stigmatised by its omission from the films but Die Another Day does feature a fairly explicit allusion earlier in the film:

Jinx: So I left you in an explosive situation. You're a big boy, figured you could handle yourself.

Bond: No wonder your relationships don't last.

It could be argued that Bond is expressing the view, entrenched in his society (and ours), that partnered sex will always supplant masturbation.

In their book How to Understand Your Sexuality internationally recognised researchers on sex, gender and relationships Meg-John Barker and Alex Iantaffi observe that:

“The culture in which we live and grow up has a massive impact… For example, solo sex has been seen, at different times in history, as an important outlet for our energies, as the cause of disease and death, as a morally suspect activity, and as only a kind of practice for the ‘real thing’”

Non-binary Bond fan Barker says: “Solo sex is always depicted as lesser than “the real thing,” and people who enjoy it as seen as questionable, childish, selfish, or abnormal.”

The need to populate a place with people who believe the same things you do is at the source of many religions’ prohibitions of male mastubration: using semen for anything other than procreation has often been viewed as a sin. In Christian cultures, masturbation is sometimes referred to as the sin of Onan, named for the episode in which a chap chooses to spill his seed on the ground than get his sister-in-law pregnant. The Catholic Church still condemns masturbation as a mortal sin on a par with homosexual sex.

Unsurprisingly, female mastubation is even less approved of in religious circles. In a 2014 article for Christianity Today, Jordan Monge noted that while “It's refreshing to finally hear women talking about female masturbation… too often the conversation doesn't overcome the unhelpful stereotypes about the female sex drive…or lack thereof. Time and time again, Christian leaders explain that women masturbate because they want to "fill a void" or have "attachment issues." These emotional generalizations fail to get at the real problem. When men talk about masturbation (or at least what I have heard and read), everyone pretty much settles on the basics: It's hard to practice self-control. It's hard to resist indulging in lust. Really hard. Few men try to psychoanalyze the process.”

There’s no hint in Die Another Day that Moneypenny is attempting to fill a void or has attachment issues. And although her session is interrupted by Q, she exhibits no shame. She’s simply having an uninhibited good time.

Shady Characters: Villains

The epitome of someone who is not who they claim to be, Colonel Moon/Gustav Graves not only has two names but two nationalities and two ethnicities. But at his core, he is a desperately insecure individual who will go to extreme lengths - even changing his DNA! - to pull off a plan which he hopes will win the approval of his father..

Moon/Graves cuts a very queer figure indeed, and perhaps one some of us can relate to.

Gay psychologist Walt Odets sums up the importance of having your family on your side:

“For young gay people, it is the acceptance and support of the family that is most developmentally significant… those who have support from immediate families clearly evidence the least developmental harm. No legislation, judicial decision, or broad societal acceptance matches the influence of authentically supportive parents-or, by itself, repairs damage wrought by a family. It is from the family that we learn to experience ourselves as lovable or not.”

It’s not clear, initially, why Colonel Moon fears the arrival of his father, the General, at his compound. But as soon as he hears of his father’s impending arrival, he tries to frantically clear away any incriminating evidence, like a queer teenager in their bedroom hiding anything which might give them away (books, magazines, internet history).

Later, it’s revealed an ideological divide is at least notionally at the root of it: the father is the dove maintaining peace between North and South Korea, the son is the hawk who wants the North to conquer all - and more. Much more. The son tells Bond that, while he studied at both Oxford and Harvard, he “majored in Western hypocrisy”. A patriotic Communist who seeks material gain, Moon is a walking contradiction, and he knows it, although blaming so much of it on Bond (and the Western values he represents) is a bit rich.

“We only met briefly, you and I, but you left a lasting impression. You see, when your intervention forced me to present the world with a new face, I chose to model the disgusting Gustav Graves on you. Just in the details. That unjustifiable swagger. Your crass quips, a defense mechanism concealing such inadequacy.”

Graves is projecting his own insecurities onto Bond. Die Another Day defender Evan Cochnar observes:

“Even before Moon’s physical transformation we learn that his father rejects him, so he was already trying to fill this emotional wound with Bondian trappings such as luxury vehicles and advanced weapons. As Graves, the character goes much further than Bond, amassing ‘toys’ including an especially phallic vehicle.”

Being ‘killed’ by Bond in the pre-titles sequence gives Moon the impetus he had been waiting for to channel his insecurities about being rejected by his father into a character, Graves, who was probably more like his true self than he cared to admit.

It’s fruitless to speculate at the exact root of a fictional character’s insecurity, the one the writers perhaps had in mind. But there’s enough in the finished film of Die Another Day for us to infer that Moon was an angry child who may have adopted radical political views as a teenager in order to oppose his father (“You've always found it difficult to accept me.”) People who feel marginalised - for whatever reason, not just being queer - are especially vulnerable to adopting radical viewpoints, which has the potential to spill over into violence.

Graves doesn’t feel good about himself which is why he drives himself to be the best at everything, including fencing and setting speed records. And unlike Fleming’s character of Hugo Drax (on who Graves is partly based), he wants to do it without cheating. That he’s beaten at both sporting endeavours by Bond grates intensely.

There’s clear evidence that Graves driving himself to be the best is driving him insane: because he doesn’t sleep he has to use a dream machine, although it’s efficacy is up for debate. When Bond quips that Graves looks like “a man on the edge of losing control” Graves quickly retorts: “It's only by being on the edge that we know who we really are, under the skin.”

Although Graves is here taking delight in dropping hints about his ‘true identity’ to an unsuspecting Bond, it also indicates that Graves now believes himself to be the closest to his true self than he ever has been before, because he’s now living on the edge (and he’s on the edge of victory).

It’s not the skin thing which causes General Moon to definitively reject his son. While he may exclaim “My son, what have you done to yourself?” while staring into his child’s altered visage, it’s Graves’s power-mad ranting that leads his father to tell him: “The son I knew died long ago.”

Despite looking like a caucasian, Graves continues to be Othered as Asian characters often are. There’s a long Western cinematic tradition of Asian characters being presented as hyper-technological, with their aptitude for advanced technologies coming at a price: they are rendered “intellectually primitive and emotionless” (Roh, Huang, et al, 2015). The Bond film series began with a cool, calculating and technologically-adept Asian villain played by a caucasian: Dr. No. Some of this ‘techno-orientalism’ is at play in the finale of Die Another Day. After coldly murdering his father, Graves struts around in his power suit like a giant robot or mecha, lashing out and making tactically unwise choices.

Trans commentator ‘0067’ see Graves’s transformation from Moon as allegorical:

“Basically Graves is a trans person but without the change in gender being shown. He's alienated from his parents who disapprove of his lifestyle. He goes off to live a new life in his new identity (definitely cis passing), and seems much happier that way. You even see his friend having to go to a medical facility in a far off country to have surgery.”

The friend in question, Zao, is feminised by Bond. After breaking into the gene therapy clinic on Los Organos and pulling off his rainbow-coloured dream mask, Bond asks Zao “Who’s bankrolling your makeover?”. Of course, we don’t know at this point that it’s Moon/Graves, with who Zao seems to have a fraternal or even homoerotic bond that goes beyond the bounds of superior officer/subordinate.

However, the trans allegory of Moon and Zao has its limitations, as ‘0067’ wryly notes:

“Sadly trans people don't have big ice palaces, discounting Elsa in Frozen, but there is a lot of interaction with lasers.”

Die Another Day does have its very own ice queen however. The fittingly named Miranda Frost is quickly coded as queer. In the Blades scene, we are invited to gaze upon her as a gay woman would, through Verity’s eyes. In the dialogue, Bond sows the seed of suspicion: she has probably succeeded in her chosen field by cheating, making her more of an archetypal (male) Fleming villain than Graves. Shortly after their first meeting, Frost makes it clear to Bond that she is sexually unavailable:

Bond: Can I expect the pleasure of you in Iceland?

Frost: I'm afraid you'll never have that pleasure, Mr. Bond.

Fans of Fleming are very familiar with his deployment of the ice queen trope, typified by characters like Vesper Lynd, Tiffany Case and Pussy Galore, all of who have their reasons for putting themself at a distance from Bond, whether they be secretly in league with the enemy, recovering from the trauma of sexual abuse or their being plain and simply (but not unproblematically) a lesbian.

The model for Miranda Frost was said to have been Gala Brand from the novel of Moonraker who exhibits “frigid indifference” towards Bond on their first meeting. The writers changed her name, from Brand (with its connotations of heat) to Frost (denotation of cold), when they decided to make the film version a traitor. The name may have changed but the ice queen DNA of the character remains.

For Fleming’s presumed ‘warm-blooded heterosexual’ readers, the tension surrounding an ice queen character was this: would Bond succeed in thawing them out and getting them into bed by the end of the adventure? The answer was universally: yes. Almost universally. It’s suddenly revealed at the end of Fleming’s Moonraker that Brand already has a boyfriend so, although she has thawed, she is still unavailable. As romance novelist Roland Hulme has astutely observed, Fleming’s novels fit the template of romance fiction quite neatly. But Moonraker subverts the typical happy ending.

In the closing pages of that novel, Gala Brand seems set to follow a heternormative path with her fiance. A true ice queen does not subscribe to such heteronormative ideals of womanhood, which perhaps explains why they attract so many queer readers.

Some of the most notable queer ice queens populating the contemporary cultural landscape include characters in DC and Marvel comics. Two female Justice League members, Fire and Ice, have long been ‘shipped by fans. Emma Frost, created by queer ally Chris Claremont for X-Men, has been a locus for intense fan speculation. Although she has not had same sex relationships in the pages of the comics or in her screen incarnations, her empowering storylines and uncompromising attitude have endeared her to gay men (that she has slept with jock boy next door Cyclops, a wish fulfilled for many gay X-fans, doesn’t hurt either).

Whether it was a coincidence or not that Purvis and Wade chose the surname Frost for their character, I like to imagine Miranda Frost is related to the X-Men’s Emma Frost, perhaps in the way that drag queens have drag mothers.

In societies where masculinity is bound up with sexual potency, male ice queens are comparatively uncommon. When they do appear they are almost always read as queer. X-Men fans speculated for decades about the sexual orientation of a male ice queen, the quite literally frigid Iceman (aka Bobby Drake), who foreswore long-term relationships and was officially outed as gay in 2015.

In a 2018 survey of current trends in lesbian (f/f) romance fiction for the Romantic Novelists’ Association, award-winning writer of “Sapphic romances” Clare Ashton encapsulated the appeal:

“The thawing Ice Queen is a favourite with readers right now. There’s so much potential for delicious tension with this one. The love-hate relationship. The frisson of discovering that the aloof woman might be gay. The unbeatable chemistry of something that feels forbidden because of the ice-queen’s natural froideur and distance.”

Ice queens have been relatable figures for queer readers and writers for centuries. The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen (who was possibly bisexual or biromantic and probably celibate) was the basis for Disney’s Frozen and many subsequent ice queen stories. Incidentally, The Snow Queen is one of Christopher Brooker’s examples of a story type with a lot of queer appeal: the Rebirth (see Bond, above).

A sign of the ice queen genre’s continuing popularity was The Lesbian Review publishing, in 2021, their list of the top 52 ‘Thawing The Ice Queen’ books. They noted that for all of the protagonists “it is about power and control”. Unlike many other fictional ice queens, Miranda Frost never thaws. She is true to her name until the end, only pretending to fall for Bond’s charms so she can distract and disarm him. For her, it really is all about power and control. It might lead us to infer that she is not really into men, or indeed anyone at all.

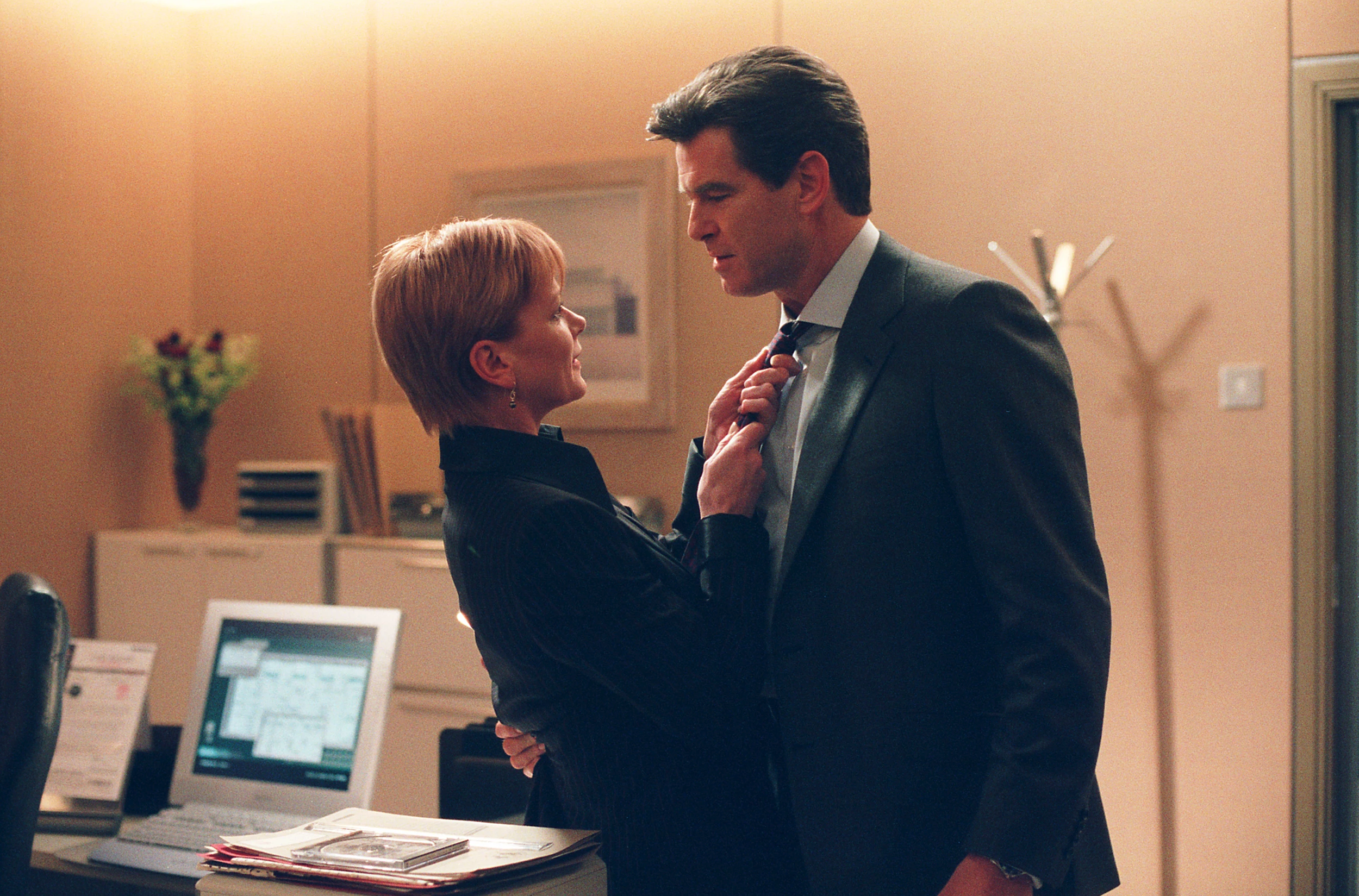

Evan Cochnar says: “Miranda Frost is a very overt exercise in the film’s themes of identity inversion and confusion, notably in the very interesting briefing scene with M in which the camera doesn’t reveal who M is speaking to, leaving the viewer assuming that M is speaking to Bond.”

When it is revealed to be Frost sitting across from M, she is interrogated by her boss about her sex life: “You haven't fraternised with any of your fellow agents, despite several advances.” Although M uses the gender neutral “fellow agents” she also deploys the verb “fraternise” (from the Latin ‘frater’ for brother) rather than the female equivalent ‘sororise’ (‘soror’ meaning sister). This is probably an unconscious choice on M’s part (fraternise is far more commonly used in everyday speech than sororise). Frost responds in a gender neutral fashion though “I think it would be foolish to get involved with someone within the community.”

When Frost and Bond do couple, it’s implied that she’s having to fake enthusiasm. Bond says the guards watching them don't look too convinced and tells her to “Come on, put your back into it.” Is Frost coded as asexual?

This subtext is brought into the text in the scene where Miranda comes out:

Graves: So when I arranged for that fatal overdose for the true victor at Sydney, I won myself my very own MI6 agent, using everything at my disposal, her brains, her talent, even her sex.

Bond: The coldest weapon of all.

With this remark, Bond intends to wound Frost, perhaps because she has wounded his pride. Unlike queer women he has managed to ‘turn’ with his magic penis in the past (most famously, Pussy Galore), Frost is not for turning.

Frost is not ‘redeemed’ (in a horribly conventional sense) by falling into the arms of Bond or indeed anyone else. Her final fight with Jinx while wearing a training bra could be seen as a concession to the straight male gaze but it could just as easily be intended to tantalise lesbian and bisexual viewers. Rather, she goes down fighting, unrepentently herself until her last breath, making her a queer heroine of sorts.

You go gurrrls

Although Giancita ‘Jinx’ Johnson is not the first of the series’ ‘female Bond’ characters, she’s the one who mostly closely mirrors his non-binary combination of masculine and feminine qualities, as well as his traits of a stereotypical gay man. Like Bond, she is rueful about her lack of long-term commitment:

Jinx: Let's just say my relationships don't seem to last.

Bond: Mmm. I know the feeling.

Their first meeting is crammed with witty repartee. This is usually the preserve of Bond himself, an element of the character which has helped him fit the stereotypical template of the gay man since Dr. No. Die Another Day has all of the main characters trying to out-pun and out-gag each other. The dialogue rarely bears any resemblance to the way human beings actually talk. The spectacularly arch confrontation between Bond and Moon/Graves in the Ice Palace provides a psychoanalytical explanation for all the quips:

Graves: I chose to model the disgusting Gustav Graves on you. Just in the details. That unjustifiable swagger. Your crass quips, a defence mechanism concealing such inadequacy.

By Graves’s logic, are all the quipping characters concealing inadequacies? (Or did writers Purvis & Wade just not want to kill any of their darlings?)

In Jinx’s case, she appears to have little in the way of inadequacy, although taking on a helicopter with an oversized silenced pistol might unwittingly support Lacan’s controversial hypothesis concerning the phallus (see discussion of Verity in Allies, above).

Jinx’s quips are less a defence mechanism and more a statement of her lack of sexual inhibition. Jinx’s dialogue is no more crass than Bond’s, but perhaps is looked on less appreciatively by some because they are not accustomed to hearing a woman being so sexually forward. It’s a double standard.

Bond: I'm just here for the birds. Ornithologist.

Jinx: Ornithologist, huh? Wow, now there's a mouthful.

Bird is British slang for ‘young woman’, increasingly seen as quite a patronising term (the US equivalent would be ‘chick’). Jinx does not appear to take offence but she does seize the opportunity to escalate the sexual tension considerably by suggestively gazing offscreen at Bond’s (offscreen) crotch.

In her actions as well as her words, Jinx is positioned as more dominant than most Bond girls. Sexually dominant women queer heteronormativity, which rests on the assumption that femininity = subservience. While our first gaze of a bikini-clad Jinx emerging from the ocean might appear to merely reinforce heteronormativity, it’s worth remembering that when Honey Ryder did the same thing in Dr. No, this also subverted audience expectations of femininity. Jinx updates the idea, with a more savage looking knife sticking out of her belt (another piece designed by gay artisans Whitaker-Malem).

Despite succumbing to damselhood at various points, Jinx sometimes has more agency than Bond. While Bond is being duped by Miranda in bed, it’s Jinx who does the spying, uncovering that Graves has the dream machine, which is the piece of the puzzle which Bond needs to work out his true identity.

When Jinx is captured she insults Zao with a phrase more commonly heard when men are insulting other men: “your mama” (British English: “your mum”). Men’s feelings of filial piety have been a target for insults for millennia (experts in Babylonian linguistics have uncovered ‘your mama’ jokes inscribed on stone tablets). Reinforcing Jinx’s masculinity in this scene, Kil intends to use a laser to cut Jinx into pieces, recalling Goldfinger’s attempt to castrate and bisect Bond. This time around, Jinx is in Bond’s place.

In her final confrontation with Miranda Frost, Jinx kills her opponent by stabbing her through the heart with Graves’s copy of The Art of War. A text which has been lapped up by warmongering men for more than two millennia, its teachings are still applied in traditionally male-domnated fields such as business and politics. In 2010, female Sun Tzu scholar Chin-Ning Chu published her The Art of War for Women in order to “provide women with the strategies we all need to overcome the obstacles that stand in the way of our goals and dreams.” The original The Art of War is perhaps not as masculine as we might think. Until the early 20th Century, it was believed that Sun Tzu made a name for himself only through the assistance of women. The story goes that when the King of Wu asked Sun Tzu to demonstrate the efficacy of his ‘art’ he did so by forming the king’s concubines into an army. His approach was not unproblematic: when they didn’t obey orders the first time he beheaded the leaders, making the rest fall into line. Arguably the same thing would happen with male soldiers (for instance, the Romans used ‘decimation’ - executing one tenth of your fighting force - to bring the critical mass under control). Although the story is probably apocryphal, it remained largely unquestioned until the 20th Century, going to show that women can be just as capable as men in the fighting arena.

This is certainly the case in Die Another Day. The sword and knife fight between Jinx and Frost is more visceral than the fight between Bond and Graves, the latter relying more on guile and gadgets than the women’s brute force and swiftly executed moves.

Theirs is the real cockfight; a showdown of two Alpha females with reclaimed phallic symbols in their grips. Even so, the women retain their essential femininity, underscored by Jinx’s final invocation to Frost, utilising a… shall we say, pejorative epithet (?) conventionally applied to women. I’m talking, of course, about “Read this, b*tch.”

Jinx vs. Frost is more dramatically satisfying than Bond vs. Graves too. On first glance, Die Another Day appears to buck the trend established in Brosnan’s tenure for the henchperson to be killed after the main villain: Boris in GoldenEye, Stamper in Tomorrow Never Dies, Renard in The World Is Not Enough. But here, the main villain (Graves) dies after the henchperson (Frost). That is, if we accept that Graves is the main villain and not Frost. Bond has a far more personal reason to despise Frost than Graves: she’s the one who sets him up in the pre-titles sequence and therefore sets the rest of the film’s plot in motion. So it would be more cathartic to have Bond square off against Frost than to have Jinx finish the job.

Social and cinematic conventions make it more acceptable to have a woman fight another woman on screen than a man fight a woman, although as recently as the previous film we saw Bond kill a female villain (Elektra). I would argue that the real dramatic resolution comes when Jinx stabs Frost through the chest. David Arnold certainly scores it as such, with the music for this section having far more bombast than the scoring for the Bond/Graves fight, which is nowhere near as heightened: the battle feels like it’s already been won by this point and Bond just needs to run the victory lap by pulling Graves’s rip cord. The effect is to reposition Jinx as the main hero at almost the last minute. It’s Bond’s quick thinking - piloting the helicopter out of the ailing Antonov - that saves them both. But the overall impression we’re left with is of Jinx taking out the main villain, in the process subverting gender norms, breaking the ‘henchperson dies after the main villain’ cycle and imbuing our memory of the film with even more nonbinariness.

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

According to Die Another Day costume artist and gay Bond fan Patrick Whitaker, this is “the Campest Bond movie that will ever be made” and I’m not inclined to disagree.

Bisexual critic Susan Sontag said that while queer people don’t have a monopoly on Camp taste, “homosexuals, by and large, constitute the vanguard -- and the most articulate audience -- of Camp”. And setting out to make something serious which cannot be taken seriously because it is simply ‘too much’ is the cornerstone of Pure Camp.

So how Pure is Die Another Day?

For a start, the visual effects are hard to take seriously, even though we’re supposed to. Seriously-intentioned but unconvincing special effects, by themselves, don’t make Die Another Day Pure Camp. As Bond fans, we have had to look charitably on B-movie back projection since day one and there are several dodgy effects moments in the films of the Craig-era.

But for many, Die Another Day simply has so many supposedly serious elements which, when combined, strain credulity until it snaps. Taken together, they give us a sense of things not fitting. The cracks in the artifice are too visible. Whether you think that’s good or bad is down to you.

Take the locations as your Rorschach test for Camp… Depending on whether you have an affinity for Camp or not, the locations are either the icing on the cake (if you love Camp) or the nail in the coffin (if you hate it). We begin in North Korea, in real-life a combination of Maui, Hawaii and various parts of England (Newquay, Aldershot). No one is convinced, let’s be honest. It’s the least authentic depiction of the ‘Far East’ since You Only Live Twice showed Helga Brandt’s plane crashing in Scotland (standing in for Japan). We move to Hong Kong (entirely on a soundstage) before jetting off to sunny Cuba… or rather, unseasonably freezing Cadiz, Spain. We could go on and on (Graves’ ice palace is partly the Eden Project, in exotic Cornwall!), but the point is: barely anything is actually shot on location. Again, using locations as stand-ins is hardly new for the Bond series, but Die Another Day takes this - as with most things - to extremes. It’s Bond turned up to 11, and all the irony that entails. Except, unlike in Spinal Tap, the irony here is unintentional - and therefore Camp in its purest form.

Sontag wrote her seminal ‘Notes on Camp’ in 1964, just prior to Stonewall and the triumphs of the Gay Liberation Movement. Since then, Camp has been shoved back in the closet somewhat. Today, Camp is not embraced wholesale by the queer community, particularly ‘straight-acting’ gay men who have not shaken off internalised homophobia. Camp and femme-shaming are endemic on today’s gay dating apps, giving rise to shorthand terms such as ‘masc4masc’ (masculine men only looking for other masculine men). But it’s nothing new: British academic Dr Charlie Sarson traces it back to the hypermasculine ideals and imagery of the 70s and 80s (‘manly’ mustaches, tight Levis), which were a rejection of the public perception of gay men popularised by media coverage of the Gay Liberation Movement.

If Die Another Day was a gay man it would be one who has a history of trying to act straight but has now learned to embrace who he is. As ever, I speak from personal experience. I first saw Die Another Day when I was a deeply-in-the-closet nineteen year old and I hated it. In fact, it was partly responsible for turning me off James Bond and sending me deeper back in the closet. For a couple of years after Die Another Day, I had a mental block in place which prevented me from enjoying James Bond. I thought it was because it was so heteronormative and I couldn’t relate to it. In hindsight, I recognise that I saw too much of myself in it. Die Another Day got underneath my skin. It was a combination of masculine and feminine - as all Bond films are! - but the straighter it acted, the more I could see through its facade. It was like looking in a mirror. Now, as an out gay man who is never afraid to embrace his feminine side, I still see all of the film’s ‘flaws’ but they’re now reasons to have fun with it. Perhaps we should all embrace Die Another Day for what it is: a quintessentially Camp artefact.

Queer Bond fans generally have a higher threshold for Camp than our non-queer friends. To get psychoanalytical for a second (analyse this!), I believe this is because we’re used to seeing through artifice in our every day lives. We are better at recognising hallowed institutions for what they are: social constructs. We’re attuned to seeing through the cracks because that’s where we’re used to existing ourselves, in the gaps between what is considered socially acceptable.

To my knowledge, there has not been a statistically-robust study of queer people’s predilections for Camp (er… why not?). But, purely from my interactions with the online community and members of my own family, I’d say we’re on pretty solid ground here. Let’s put it this way: while A View To A Kill is a favourite of many gay men, I don’t hear a lot of straight men loudly and proudly putting it in their top five.

The difference between Die Another Day and a film like A View To A Kill is that A View To A Kill is trying to be Camp. It nudges the audience - and winks, and raises an eyebrow.

Sontag insists that “Pure Camp is always naive”. If not as pure as the driven snow, Die Another Day is at least as pure as the snow after it’s been churned up by an Aston Martin Vanquish duelling with a Jaguar XKR.

In early 2006, Die Another Day’s director fell foul of a Los Angeles Police Department crackdown on gay prostitutes. When Lee Tamahori offered to perform oral sex on someone for money the person in question was, unfortunately for Tamahori, an undercover police officer. A classic case of entrapment with policemen used as agents provocateur, Tamahori only avoided up to six months in prison by not contesting the charge of criminal trespass (getting into the officer’s car), meaning the charges of prostitution were dropped. His sanction was three years probation, 15 days of community service and mandatory attendance of an Aids awareness course.

The prudish press had a field day with many jumping to the conclusion that Tamahori had been living a ‘double life’. Two elements in particular made it particularly headline-grabbing. Firstly, that Tamahori was wearing a little black dress when he propositioned the policeman. And second, that he had once directed a Bond film. The two must have seemed like a sensational contradiction in terms. A particularly gleeful version of the story appeared in The Times under the headline ‘Bond director is arrested for selling sex in a dress’.

Tamahori has never put a label on his sexual orientation or his gender identity. He has been married to women and a supposed ‘friend’ of his revealed that during the London shoot of Die Another Day, Lee made the most of his time off by dressing up in latex and frequenting London’s fetish clubs with his girlfriend. It’s rarely a good idea to speculate about people’s identities. And however Tamahori identifies, it really is no one else’s business. But who knows… being half-Maori, Tamahori may consider himself to be ‘takatāpui’ an umbrella term like ‘LGBTQ+’ which has existed in the Maori language since pre-colonial times. The term managed to survive the British making buggery illegal (as they did throughout their colonies in the 19th Century) and it has been popular with younger queer Kiwis since the 1980s. Tamahori’s breakthrough film, the brilliant and challenging Once Were Warriors (1994), explored gender expectations and norms within the Maori community, with the female characters emerging as the heroes. Perhaps not so different from Die Another Day as it first appears. Does that support a case for the twentieth Bond film being the work of an auteur?

With its onslaught of homages to 40 years of Bond heritage, those with a low tolerance for fourth wall breaking will loathe Die Another Day. Personally, my threshold is pretty high, although it’s taken me two decades to get over the use of The Clash’s London Calling, in large part because it replaced a David Arnold cue (which appears on the extended soundtrack album). Many viewers deride the gunbarrel, with the bullet (usually assumed to be there but unseen) flying straight at the screen. The gunbarrel is always one of the campest elements of any Bond film (it’s so posed and artificial how could it not be?) but not everyone is in on the joke. Perhaps people don’t like this one because it makes them realise how ridiculous all of the others are.

There are a few Hot Bond Boys With Bit Parts. Colin Salmon’s limited screentime means he arguably qualifies. It’s a welcome return for the very visually appealing actor. One of the guards on the jetty which takes Jinx and Bond to Los Organos would also be worth buying a Mojito for.

The thematically on-point fire and ice opening titles blur the lines between pleasure and pain in a way that BDSM-fan Ian Fleming would have approved of. But what would gay poet A E Housman have made of a line from one of his poems, written more than a hundred years before, being used to title this deliriously daft film and its song? I would like to imagine him, finally, happy.

Queer verdict (005 of 007)

A little like being imprisoned and tortured in a North Korean jail for 14 months, Die Another Day is not an experience you would recommend without some reservations. It bravely resists giving up its secrets and you have to look beneath the surface if you want to get the most out of it. It’s acutely uncomfortable because it shakes up the system, refusing to be pigeonholed as a particular narrative, gender or sexual orientation. But if you’re prepared to avoid the cliches and you don’t write it off wholesale, you’ll find there’s so much more to know. I need to lay down.

Acknowledgements

Ardent Licence To Queer supporter Evan Cochnar has something of a reputation as an apologist for Die Another Day and he’s responsible for my prioritising of this film over the others I haven’t got around to yet. His own thoughts about the film were very helpful in approaching the dual mission aspect and particular characters. This one’s for you Evan.

Licence To Queer contributor ‘0067’ helped me see the film through a trans person’s eyes.

Thank you to Instgram follower crarb for introducing me to techno-orientialism and its tropes.

Novelist Roland Hulme and I have an ongoing discussion about Fleming as a writer of romance fiction, some of which made it into this piece. Check out one of our discussions here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NIdv9MCrBe4

The lovely and immensely talented Patrick Whitaker generously fielded all of my queries about his involvement with the production of Die Another Day.

My discussions with Claire Birkenshaw led to several lightbulb moments on my part, especially in relation to binary thinking and its origins.

Some of the images above were sourced from the always brilliant Thunderballs.

It has taken six months from start to finish to write this queer re-view, during which my husband Antony actually requested to watch Die Another Day twice, thereby assisting my research no end. Some of his observations about Miranda Frost (his favourite character) made their way into this piece. Thank you darling.

References

Ari (2018) ’The Sports That Made You Gay, Ranked’ Autostraddle Available at: https://www.autostraddle.com/the-sports-that-made-you-gay-ranked-432462/

Ashton, Clare (2018) ‘Romance between women who love women’ Romantic Novelists’ Association Available at: https://romanticnovelistsassociation.org/2018/10/clare-ashton-romance-between-women-who-love-women/

Associated Press (1987) ‘Thatcher Says Former Spy Chief Was a Homosexual’ AP News Available at: https://apnews.com/article/c8c0adab1d2edc9a779b05ff4f3d4853

Ayres, C (2006) ‘Bond director is arrested for selling sex in a dress’ The Times Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/bond-director-is-arrested-for-selling-sex-in-a-dress-mdsv7qx6r0b

Buhrke, Robin A. (1996) A Matter of Justice: Lesbians and Gay Men in Law Enforcement Psychology Press

Barbakadze, Nini (2021) ‘Whitaker Malem: Pop Artisans’ Metal Magazine Online https://metalmagazine.eu/bi/post/interview/whitaker-malem

Barker, M.J. and Iantaffi, A (2021) How to Understand Your Sexuality: A Practical Guide for Exploring Who You Are London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Brooker, C (2004) The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories London: Continuum

Butler, J (1993) Bodies That Matter – On the Discursive Limits of Sex, London: Routledge

Century, S (2020) ‘The very weird subtextual love of Fire and Ice’ Syfy Available at: https://www.syfy.com/syfy-wire/the-very-weird-subtextual-love-of-fire-and-ice

Corera, G (2021) ‘The challenge of being gay and an MI6 spy’ BBC News Online. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-56211665

Criado-Perez, C (2014) Caroline Criado-Perez on Judith Butler: What’s a phallus got to do with it? The New Statesman Available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2014/05/caroline-criado-perez-judith-butler-whats-phallus-got-do-it