“Keep the fruit”: mixing up Felix Leiter’s masculinity

The line didn’t exist in the earlier drafts of Casino Royale. Is it just a throwaway quip or something more revealing of Felix’s character?

This article is available as a podcast wherever you get podcasts.

After asking the bartender to make him a Martini to Bond’s exacting recipe in 2006’s Casino Royale, Felix Leiter commands him to make just one change: omit the lemon peel. Both this line and the character of Felix Leiter do not appear in the screenplay finished on 13th December 2005 (close to filming).

The “Keep the fruit” line does appear as the rather more polite “Can I have one without the lemon?”, but it’s spoken by Tomelli, one of the undeveloped poker player characters, not the character who is later revealed to be working for the CIA, Wolpert. This new character’s dialogue was given wholesale (with minor modifications) to returning character Felix Leiter following the casting of Jeffrey Wright.

So why did they give Tomelli’s line to Leiter and make it sound like more of a command than a polite request?

Felix Leiter is accustomed to playing second fiddle to Bond. In most stories he’s the archetypal ‘helper’ character, not dissimilar to a Bond Girl in this regard. The only difference is, Bond doesn’t sleep with Felix, although any queer Bond fan who has read Fleming’s Diamonds Are Forever would probably dispute this. Some of this translates to the films as well. Many of us have years of experience shipping James and Felix. See for instance, this very persuasive piece by Kathleen Jowitt and the Allies sections of my own queer re-views for the films where Felix makes an appearance.

The relationship between James and Felix even has a name which is frequently used in the fandom, a portmanteau of their first names: ‘Jalix’.

And while it is never wise to ask a gay couple in real life who is the ‘bottom’ and who is the ‘top’, Leiter has traditional been portrayed with a subservient status.

In the novel of Casino Royale Felix expresses astonishment at the size and strength of Bond’s Martini. Right from the start, masculinity in the world of Bond has been measured by how much you can take your drink. In the films, Felix’s masculinity is more muted than Bond’s in subtle ways: he often wears lighter coloured, less conventionally ‘masculine’ clothing than Bond. In Dr. No, he even wears a pair of very fetching cats eye sunglasses which may have been groovy for all the cool cats in the 1960s but have since become marked for gender.

In extremely crude terms (and please never say something as ignorant as this to real life gay men), Felix is the woman and Bond is the man. And this is despite his being from Texas - with all the masculine baggage that entails. [Incidentally, Bond designer Tom Ford has spoken very eloquently about growing up gay in Texas. In a nutshell: it wasn’t easy!]

The roles assigned to James and Felix remained largely unchallenged for fifty years, until Casino Royale mixed things up a bit.

Jeffrey Wright’s Felix Leiter comes across as a combination of both the lighter-hearted Leiters (the early Connery era) and the no-nonsense ‘straight man’ versions (Diamonds Are Forever onwards). He’s still very much the helper but, rather than merely following Bond around cleaning up his messes and getting on with things behind the scenes to move the plot along, in both Casino Royale and Quantum of Solace he comes through in a crisis for Bond. He’s there for Bond when he’s really needed.

In both films, there is genuine romantic onscreen chemistry between Daniel Craig and Jeffrey Wright. And like a real life couple, their relative status is less clear cut: like many mature gay couples, they’ve got past the rigidly defined bottom/top stuff and just got on with doing whatever feels good.

What does all this have to do with a slice of lemon peel in a Martini?

Thanks largely to James Bond, we all know that the way someone orders a Martini says a lot about that person. The filmmakers complicated things further by bringing ‘fruit’ into the equation. The word ‘fruit’ has been used as a slang term for gay men since at least the Second World War, perhaps because fruit is commonly thought of as soft (when ripe at least) and feminine. Certain fruits and vegetables are so commonly used as stand-ins for parts of the male anatomy that thay have become standardised in gay culture (and further afield), especially when used in the form of emojis. See, for instance the peach (which has a long history before hitting the mainstream via Call Me By Your Name) and the universally-recognised aubergine/eggplant. Any produce with a phallic-shape gets co-opted to locute about gay sex: bananas and cucumbers took on additional queer connotations thanks to a Russell T Davies 2015 project.

When Felix gruffly commands the bartender to ‘Keep the fruit’, it opens up possibilities: is he asserting his masculinity over Bond and the other players by rejecting their ‘fruitiness’? Is he ‘protesting too much’ and trying to hide something about himself he doesn’t like? Is he just not a fan of lemon?

But there’s more to this than just a slice of lemon. Beyond the garnish, what about the drink itself, one of the strongest beverages on the mixologist’s menu, sipped from a vaginally-shaped receptacle on a delicate stem? The Martini is - inherently - a crisis of masculinity in a glass.

When you stop and think about it, it’s hard to think of a ‘gayer’ drink than Bond’s Martini. It’s hard to think straight - or at all - after you’ve had more than a couple of them.

Mother’s Ruin

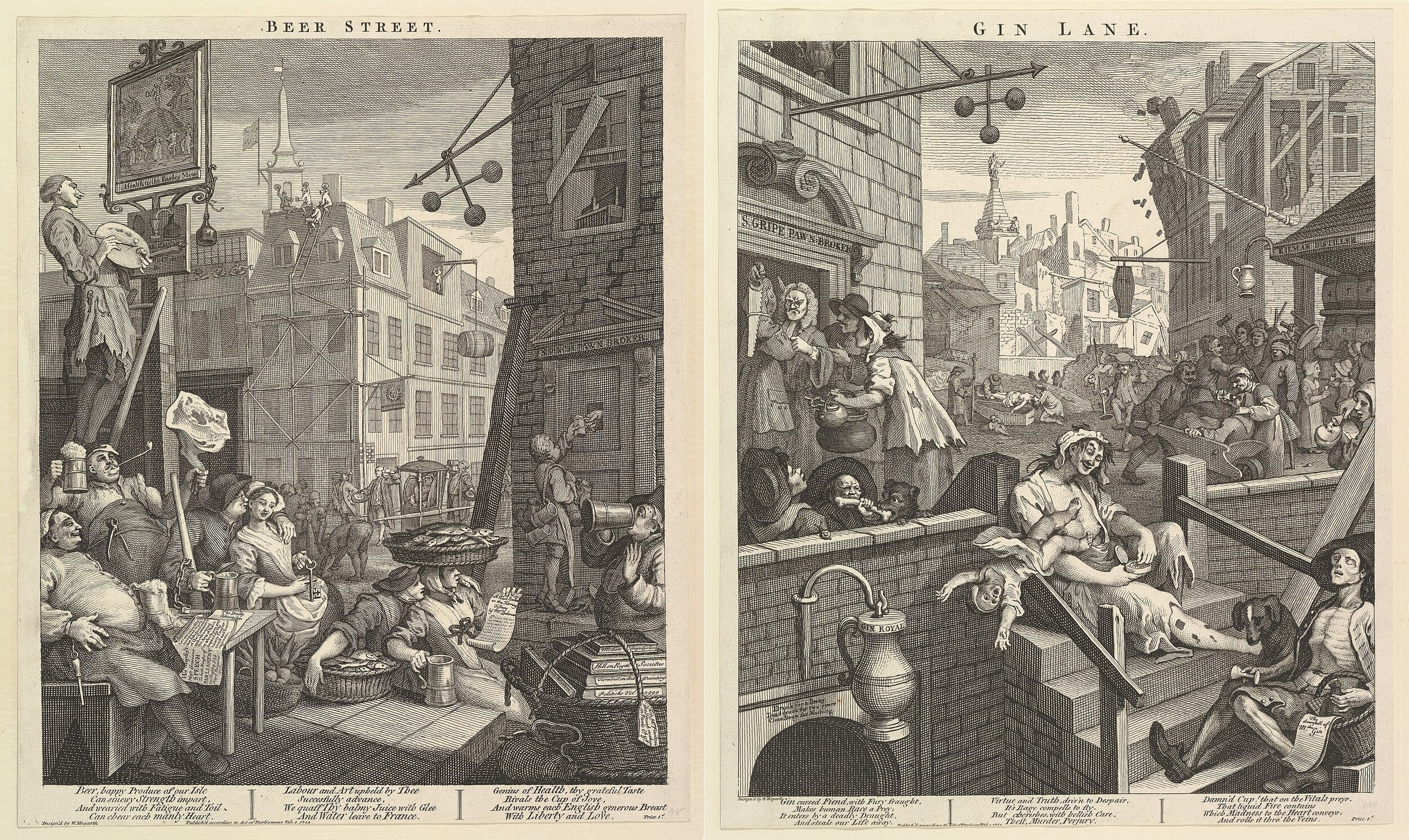

Whether you prefer it with lemon (like Bond) or without (like Felix), a true Martini is still mostly a glass of gin, a spirit which is still known here in the UK as Mother’s Ruin, a label it acquired in the 18th Century. There’s a degree of truth in gin-drinking contributing to women turning to prostitution and neglecting their offspring, as depicted in William Hogarth’s famous prints, including 1751’s deeply unflattering portrayal of Gin Lane, a visual distillation (pun intended) of the newspaper headlines of the time. Contrast the deplorable Gin Lane - as the despairing British government implored the populace to do - with the idealised Beer Street.

In Beer Street, citizens are shown pleasantly carousing rather than cavorting, debauching and self-destructing as they do on Gin Lane. The ‘Gin Craze’ of the 18th Century was undoubtedly a public health nightmare, with thousands of Londoners addicted to cheaply made and potentially poisonous gin. The government was eager to switch the drinking public onto less-strong stuff. But the spirit itself was also a victim of a smear-campaign by beer producers: they commissioned Hogarth’s bestselling prints and beer became pre-eminent when the Duke of Wellington oversaw legal changes which made beer cheaper to make and sell. Beer became Britain’s drink of choice ever after, at least among working class men.

The gender double standard - that it’s more socially acceptable for men to be beer drinkers, and drinkers in general - existed back in the 18th Century: the Beer Street sketch shows a couple of women enjoying a beer but it’s already a male-dominated scene.

Gin’s popularity has fluctuated considerably in the interim, although it has usually retained a metropolitan (feminine) connotation. The mid-19th Century saw a resurgence in its being socially acceptable, with ornate Gin Palaces popping up all over London. And envoys of the British Empire drank it with tonic water, ostensibly to ward off malaria (although the quantity of quinine that would have been required to give the drink any medicinal properties would have rendered the drink unpalatable). The British Navy’s contributions to cocktail culture cannot be underestimated, although it must be noted that gin was routinely consumed more by officers than privates, who were rationed with rum instead.

In the latter half of the 20th Century, we can credit Smirnoff with successfully persuading many to switch to vodka by making people self-conscious about the smell of their ‘ginny’ breath. Their “leaves you breathless” ad campaign began in 1953, the year Casino Royale was published.

No wonder Fleming started having Bond drink vodka Martinis as early as the second novel, Live And Let Die. Gin was seen as old fashioned, upper class, stuffy and a bit effeminate in comparison with clean and clear vodka. While the Bond of the novels does continue to order gin-based drinks from time to time, a product placement deal with Smirnoff for the film of Dr. No secured Bond as a vodka drinker in the popular imagination until 2006’s Casino Royale. By this time, vodka’s popularity was waning and gin was already staging something of a come back.

Not-so-straight up

You could say the gays helped set the trend. Gin has long been a big hit with gay men. Like ‘fruit’ (and other words, such as ‘faggot’) we have frequently been associated with things that are feminine. A book-length study of the Martini (Martini, Straight Up) by Lowell Edmunds, a classics professor, enjoyably teases apart many of the complexities of the drink, including its apparent genders. Edmunds concludes that “appreciation of the Martini was a woman’s as much as a man’s province”.

In Bond films, the Martini has historically been more of a man’s drink. GoldenEye’s Xenia Onatopp bucks the trend, ordering the same vodka Martini as Bond, ‘straight up [without ice] with a twist’. The aim is to show her as Bond’s equal and she is often shown in quite masculine clothing, coding the character as queer. She is more than coded as queer in the uncut version of the film where she propositions Natalya, telling her to wait her turn until she has ‘taken care’ of Bond in the jungle.

Something interesting happened with the switch to gin Martinis from Casino Royale onwards: women started to enjoy them, including the most significant women in Bond’s life: Madeleine matches Bond Martini for Martini in Spectre’s train scene, a sure sign that she’s ‘the one’ in Bond’s mind. Previously, Vesper Lynd had an approving sip of the gin-based concoction named for her. Compare, though, the scene where Vesper tries the gin Martini for the first time in Casino Royale with the scene where Licence To Kill’s Pam Bouvier downs the vodka Martini left behind by Bond. Not exactly the most feminised of Bond girls, Bouvier nevertheless winces her way through his manly drink: it’s too much for her is the message. Perhaps she would have preferred a gin Martini?

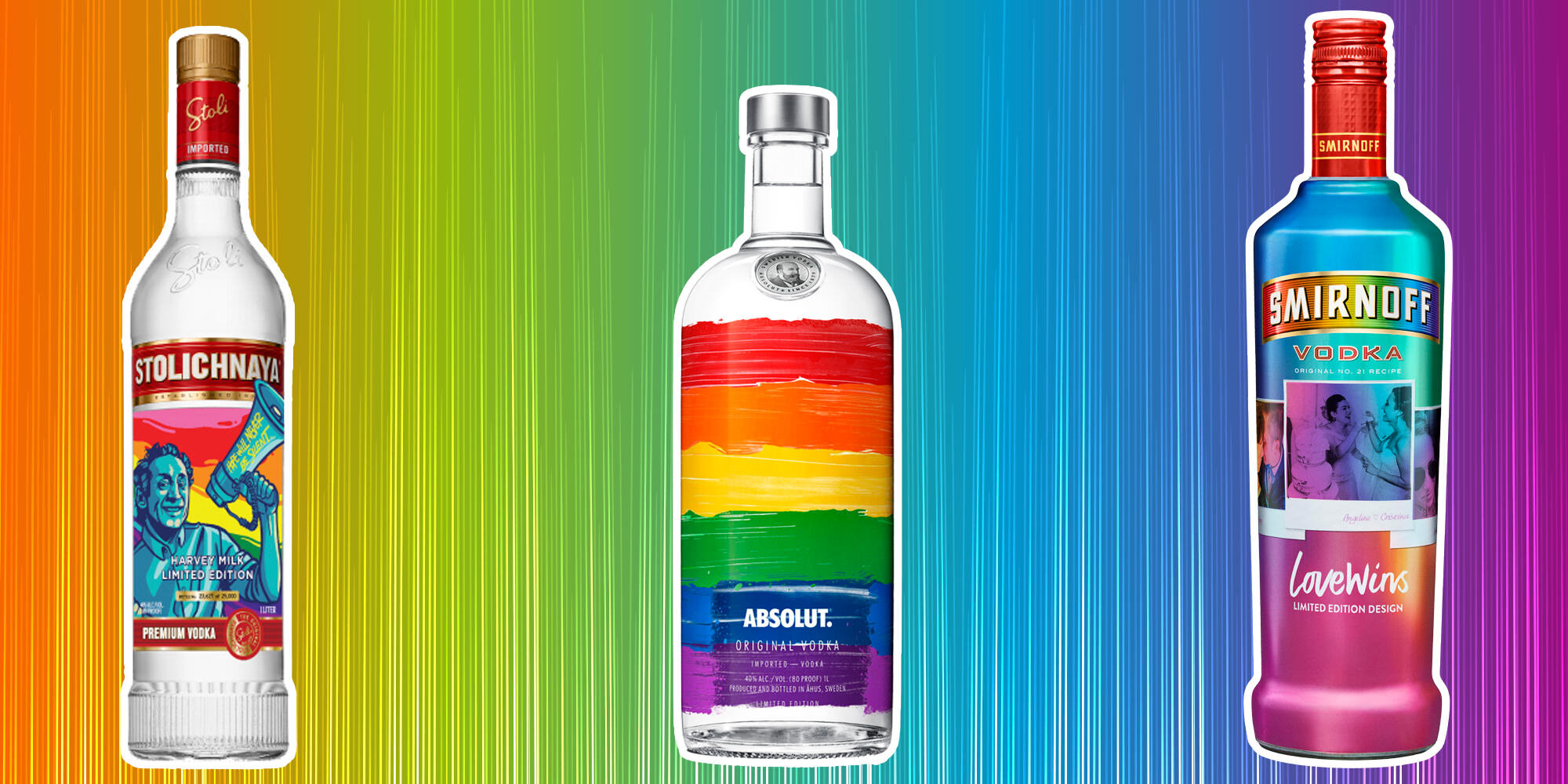

As it happens, vodka had become something of a gay drink itself, one that is “synonymous with Pride”. A combination of clever marketing campaigns aimed at LGBTQ consumers and vodka containing fewer calories than other drinks (such as beer) has secured its queer popularity, although gin is starting to regain its ground from earlier in the 20th Century.

The strong stuff

Kara Milovy makes Bond a vodka Martini in The Living Daylights without trying it herself, although it’s probably the inclusion of additional ingredient chloral hydrate that dictates this decision! Even without knock out drugs shaken into the mix, some think the Martini qualifies as ‘manly’ due to its sheer strength.

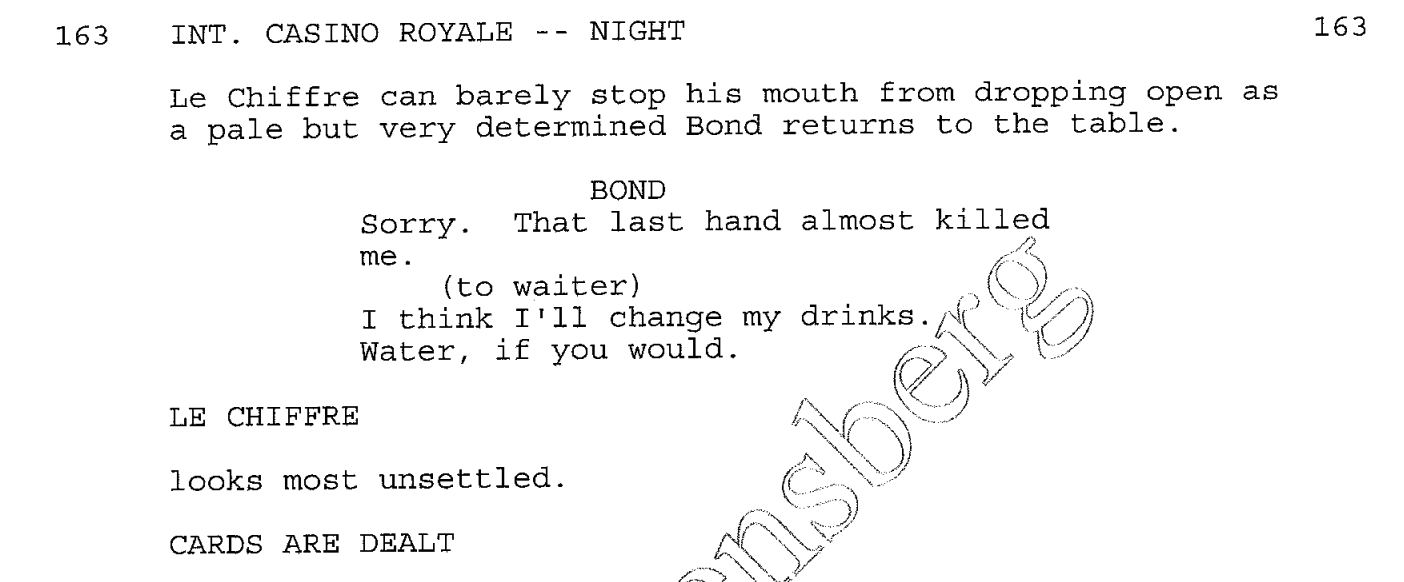

A deleted line of dialogue from the December 2005 draft of Casino Royale reveals that even Bond recognises when it’s time to switch to water, a moment familiar to all Martini drinkers but apparently alien to Ian Fleming’s superspy, who downs vast quantities of booze before setting off into danger.

Was this line deleted purely for time reasons or was there a fear that it would make Bond appear more feminine? Being able to hold one’s drink is allegedly a manly quality. Bond’s order of water signals to Le Chiffre that he’s going to be taking the game more seriously. Does it also threaten his masculinity?

Interestingly, in a 2020 Heineken advert for No Time To Die, a tuxedo-ed Daniel Craig does something similar, preferring a non-alcoholic beer over his Martini. His reason? “I’m working”. Some less enlightened commentators on forums and social media decried the advert as ‘woke’, which I suppose answers the ‘does it threaten masculinity?’ question.

Like Bond ordering water in the line deleted from Casino Royale and Craig in this advert, I know my limits. And I won’t let insecurities about my identity override them. I enjoy a beer (grrrr, manly) as much as a gin-based drink. In my twenties, I might have let social convention - who I was with and where I was - dictate which drink I ordered. Nowadays, I will just order whatever I want or whatever goes best with the food I’m about to eat. While I identify as a man, I don’t feel a need to constantly reassert my masculinity. Perhaps this means I have a ‘muted’ sense of my gender, as if the volume was turned down and I don’t feel the name to shout ‘I AM A MAN!’ literally or metaphorically in anyone else’s face. Perhaps this is one of the priveleges of being gay: it causes you to question things and makes you realise how ridiculous much of social convention really is.

If you like fruit in your Martini, stick with the fruit. If you don’t like fruit, have it with something else. Perhaps a glacé cherry (classy!). Or some pepper (another of Bond’s favourites). Let’s be a bit more grown up about these things, shall we? Martinis all round!

Additonal references (not already cited) and further reading

I first came across the term ‘muted’ to describe gender in the excellent book Gender: A Graphic Guide by Meg-John Barker and Jules Scheele.

For more on character archetypes, see my queer re-view of Tomorrow Never Dies:

https://www.licencetoqueer.com/blog/queer-re-view-tomorrow-never-dies

Propp’s original paper from 1928 is available here:

https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/propp.pdf

For my other discussions of the stereotypes associated with particular drinks:

Mojito: https://www.licencetoqueer.com/blog/mo-he-to

Negroni and the Americano family of drinks: https://www.licencetoqueer.com/blog/please-drink-risico-ly

https://www.licencetoqueer.com/blog/campari-ing-it-up-with-007