“Homos make the worst killers”

Wint and Kidd are some of the most ‘problematic’ characters in the Bond series - but I’ve loved them since setting eyes on them in Diamonds Are Forever, when I was aged eight. In an effort to work out the root of my unhealthy obsession, I decided to re-read Fleming’s novel and ended up with more questions than answers. Are they even gay? Why is one of them nicknamed ‘Boofy’? And what does my attraction to such horrible characters reveal about me?

I’m often asked by other Bond fans, ‘What do you make of Wint and Kidd?’. If it’s a fan who identifies as straight asking me the question, I presume that they expect me to launch into a unflinching condemnation of the characters’ undeniably homophobic representation. But it’s more complicated than that.

Every time I watch Diamonds Are Forever I’m left feeling a bit weird, like I’ve been complicit in betraying myself, and queer-kind as a whole. Wint and Kidd are loathsome depictions of queer characters. And yet, I keep coming back for more, like a puppy still desperate for a scrap of affection from its abusive owner.

Wint and Kidd were in no small part one of the reasons I started Licence To Queer and why my first ever extended piece was my queer re-view of the film of Diamonds Are Forever. In that article I attempted to argue (to myself, as much as to anyone else) that Wint and Kidd are representations that we (gay male viewers) should take to our hearts. They are, after all, a loving same sex couple, something that is still little seen on screens. In 1971, it was virtually non-existent. Yes, they’re hired assassins who think nothing of drowning little old ladies and offing Las Vegas entertainers in their dressing rooms but, well, nobody’s perfect.

In any kind of objective reality, Wint and Kidd are a million miles away from being positive role models. But compared with the commitment-phobic, non-monogamous Bond they are almost ‘normal’ by comparison. I’m not for a moment suggesting that monogamy should be placed up on a pedestal. Many find it far too confining, claustrophobic even. I know many people in entirely satisfying polyamorous relationships.

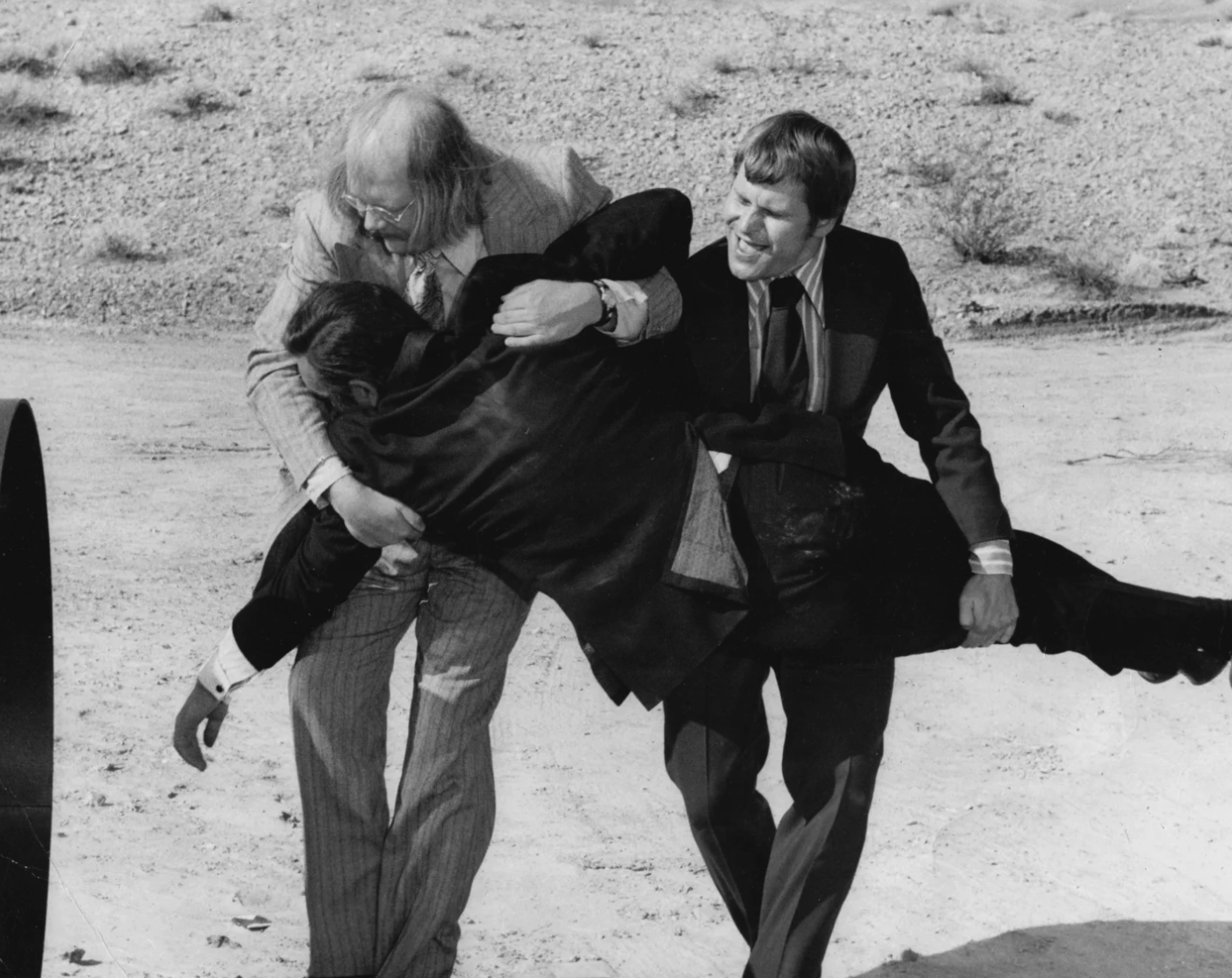

But for me growing up, I couldn’t imagine being in a relationship of any kind with another man. As perverse as it sounds, Wint and Kidd represented some kind of ideal. Most thrilling to me was the idea that, whatever they got up to in their bedroom, this was two men in love with each other. The shot in the film of Wint and Kidd walking hand in hand through the desert has been burned indelibly into my consciousness ever since I saw the film for the first time, aged eight.

Less clear in my memory was their presentation in the novel of Diamonds Are Forever. I first read this in my early teens and it was with trepidation that I returned to this novel as an out and proud gay men in my late thirties. I dimly remembered the novel’s Wint and Kidd being presented less sympathetically than their film counterparts. Would Fleming’s Wint and Kidd make me wince?

In short: yes. Although not as much as I winced at Fleming’s treatment of “coloured people” only four pages before Wint and Kidd make their entrance. Time and again I have argued on this page that no matter how problematic something is, you can still enjoy it. But this extremely racist passage, where Bond reflects on “how lucky England was compared with America where you had to live with the colour problem from your schooldays up”, before retelling a joke involving the word “negro” (which I can’t bring myself to type out), hit me like a punch to the gut when I re-read it a few days ago. Added to this is the revulsion that Bond feels at a black man’s hands slathering mud over his body and you arguably have a potent combination of both racism and homophobia (although Bond doesn’t mind at all having white male masseuse’s hands on him in the novel of Casino Royale).

This whole sequence in the novel of Diamonds where Bond is having a mud bath while surrounded by naked men is erotically charged. Entering into this homosocial environment: Wint and Kidd, who proceed to sadistically pour boiling mud over another man, with Bond rendered (conveniently) unable to intervene. They are depicted as hooded, but their identities are revealed near the beginning of the next chapter by Felix Leiter. Leiter tells Bond that Wint and Kidd “always work together” and speculates that the “pretty boy” Kidd “probably shacks up with Wint”. Leiter also reveals that Kidd’s friends call him ‘Boofy’, the real life nickname of one of Fleming’s friends, and a relative of his wife.

Fleming was no stranger to using his friends’ names for his characters. In Diamonds Are Forever, Ernest Cuneo (to which Fleming dedicates the later novel Thunderball, describing Cuneo as his “Muse”) lends his name to the heroic taxi cab driver. It’s a rather flattering portrait. But in the case of ‘Boofy’, the real-life subject was not amused.

Arthur ‘Boofy’ Gore was not gay himself, but his brother was. He inherited the title of Earl of Arran from his brother, who sadly killed himself in 1958. In the ensuing decade, Gore was a vociferous supporter of the decriminalisation of homosexuality and, in 1965, sponsored a bill through the House of Lords that would lead to 1967’s partial decriminalisation. Who knows what spurred on Gore, who apparently became an alcoholic throughout this period, before drying himself out when the bill was passed into law. Clearly something was eating away at him: guilt that he couldn’t do more for his brother perhaps?

Diamonds Are Forever was published two years before the death of Gore’s gay brother. By all accounts (including the biography of Fleming by Andrew Lycett), Gore did not appreciate Fleming borrowing his nickname for Kidd. In Lycett’s words: “Ian had done his usual tricky of assigning the names of friends and acquaintances to his characters”. Perhaps, as he usually did, Fleming intended this instance to be taken in good humour. Or maybe he intended it to be a snide commentary - for those in the know - on Gore’s sympathetic feelings towards gay people. As far as we know, Fleming did not make a statement on the subject. From what I know of Fleming, I find it hard to imagine him stooping so low.

Appellations aside, what should we make of Fleming’s creations?

It’s important to note than neither Wint not Kidd are explicitly identified as gay. It’s Felix who has joined the dots before concluding that “Some of these homos makes the worst killers”. Felix intends it to be a compliment of sorts - they’re the “worst” because they’re so good at their job. But his branding of them as “homos” is arguably specious.

He’s certainly drawing conclusions from a very sketchy set of evidence. Aside from some vaguely effeminate stereotypical behaviour (Wint is not a good traveller; Kidd is vain about his prematurely white hair), there’s really nothing to go on. This is especially ironic considering Leiter’s own behaviour in Diamonds Are Forever. He’s practically joined at the hip with Bond, despite working for different agencies to purportedly different ends. There’s no convincing reason for Leiter and Bond to be together in this book.

After reconvening on the streets of New York, Felix takes Bond for an intimate, boozy lunch. Before they part, he takes Bond “affectionately by the arm”. They then head out on a romantic two hundred mile road trip in a “Studillac”, during which they talk mostly about the size of their respective engines. They share several more intimate meals, during one of which we are told Leiter “looked affectionately” at Bond (that word again!). Their evening comes to an end when Leiter says “Let’s go home to bed and give your shooting eye a rest.” Okay, you get the idea! And yes, this is all very circumstantial. But it adds up to a hell of a lot more than Wint and Kidd.

When Bond re-encounters Wint and Kidd at the end of the novel, there is nothing in their behaviour to suggest anything other than a professional relationship. Fleming does drop a possible hint with one of his always-interesting uses of the word ‘queer’. Wint and Kidd place a bet that the ocean liner they’re aboard will make poor time. Later, it becomes apparent they planned to drop Tiffany (and possibly Bond) overboard, thus forcing the ship to slow down and look for them and - therefore - winning their bet. Not knowing this, Bond describes their betting as a “queer business” because the “sea’s as calm as glass” (I.E. everyone expects them to make good time). The only other inkling that Wint and Kidd might be romantically involved comes after they are dead, when Bond has remade their demolished cabin and moved their corpses to make it look like Wint has killed Kidd and then killed himself. He supplies a possible fictional motive - “remorse” - but goes no further. There’s no suggestion that Bond thinks the remorse could be due to one lover having killed another.

Bond takes no pleasure in killing them either. In fact, the end of Diamonds Are Forever is one of Fleming’s more melancholy finales. He even has Bond imagine the dead Wint speaking to him: “Only death is permanent. Nothing is forever except what you did to me”.

Compare this with the outrageously camp - but paradoxically heartfelt - climax of the film of Diamonds. Unlike the novel’s Wint, who barely registers the death of his partner beyond screaming a little, the film’s Wint is clearly heartbroken that his partner, aflame, has just jumped overboard an ocean liner. Bond then proceeds to make Wint exit the same way with his “tails between his legs”, abusing Wint’s erogenous zones as a sort of schadenfraude at Wint’s expense for his same sex attraction. Bond literally gives Wint a prostate massage with a ticking time bomb. It’s a horribly apt way of killing a gay man and raised all sorts of questions in my eight year old brain about what makes gay men physiologically different to straight men. That it took me well over a decade to find out the answer is an indictment of sex education in the 1990s (and, one fears, still too many schools today). Diamonds Are Forever reinforces the misconception that there IS something aberrant in the biology of gay men. The truth is that all men are born with a prostate but, if a straight guy is under the misapprehension that it’s too ‘gay’ to find out what it’s for, then it’s their loss!

Although the film’s portrayal of gay characters is deeply problematic, I prefer it to the book’s equivocal treatment. Re-reading Diamonds, I was struck by how bland, how un-gay, Wint and Kidd were compared with their film incarnations. I was, in all honesty, disappointed that they weren’t flouncing around spraying perfume on themselves, slipping scorpions down people’s shirts and concocting elaborate ways of killing a particularly slippery spy; does it get more gleefully sadistic than trying to cremate someone while they’re still breathing? Or leaving them in a pipe in the middle of the desert, knowing they will find themselves buried alive when they wake up? I don’t think so!

And each time, they walk away, hand in hand.

Thirty years ago, they provided this gay Bond fan with a template of sorts. I could one day, maybe, have a relationship with someone of the same sex! I dread to think what this says about me; that I looked straight past their day job, their murderous modus operandus, and only saw the romance. The reality is, when you’re starved of visible role models, you learn to take whatever you’re given.

These homos may make the worst killers, but - for an impressionable eight year old - they also made some of the best lovers.

For more of my thoughts on Wint and Kidd in the film version of Diamonds Are Forever, check out my queer re-view: https://www.licencetoqueer.com/blog/diamondsareforever

Behind the scenes images/production stills taken from https://www.thunderballs.org/

As usual, unless otherwise stated, all rights reserved to Danjaq LLC. / EON Productions, United Artists Co., MGM Studios, Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, Sony Pictures Inc.