(Gold)finger food - and lots lots more

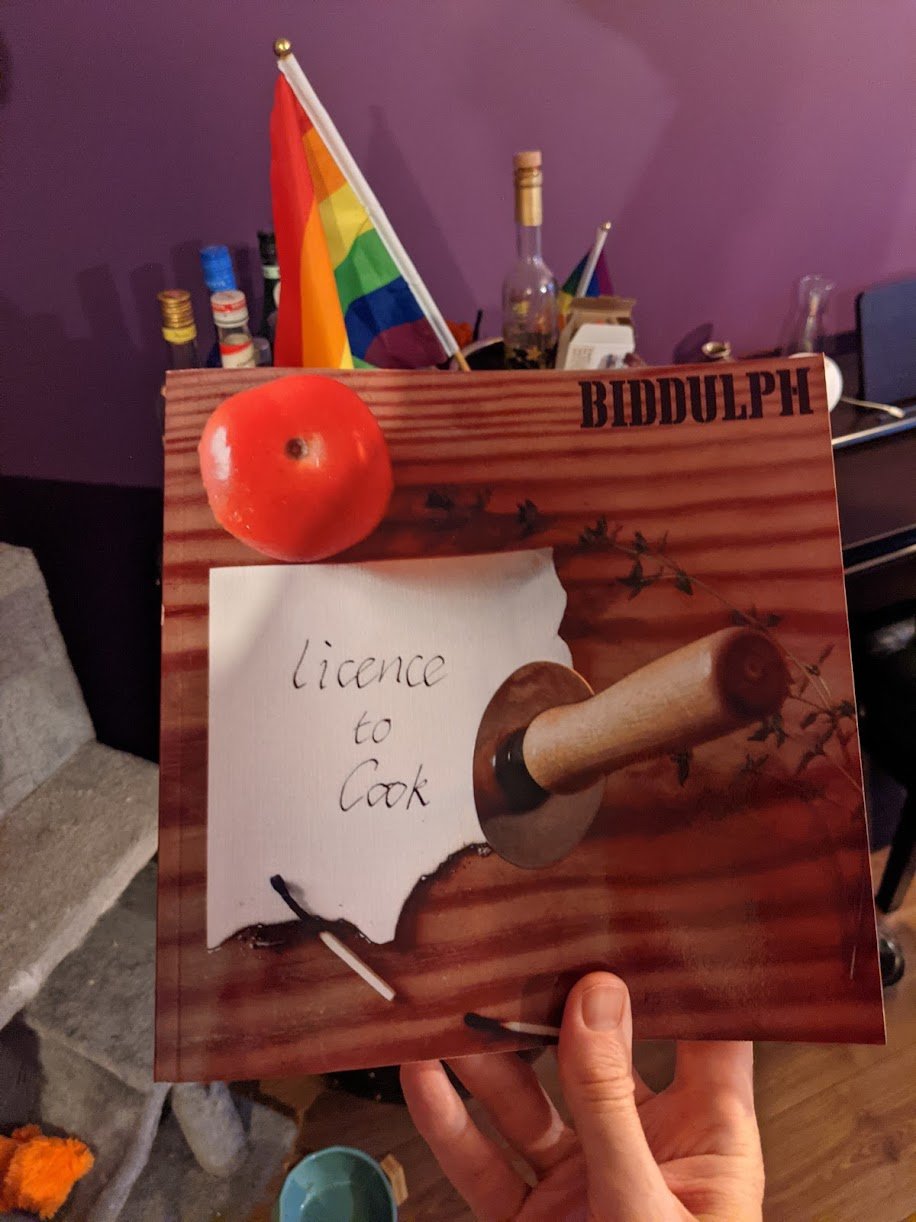

Friend of Licence To Queer, Edward Biddulph (author of Licence To Cook) takes us on a guided tour through the somewhat gluttonous Goldfinger. Be warned: the multifarious delights are mouthwatering and sometimes messy. Better bring the napkins.

Goldfinger may not be the most prolific of Fleming’s Bond novels in terms of food mentions – that accolade can probably be given to Diamonds Are Forever, with its twenty out of twenty-five chapters containing some reference to food, compared with fourteen out of twenty-three chapters in Goldfinger – but the food it describes is arguably the most varied, tempting, and culturally significant.

The American food bookends the adventure. Almost from the very the beginning, readers are introduced to one of the most luxurious meals Bond consumes: stone crabs smothered with melted butter. It’s so good and indulgent, that Bond declares it the most delicious meal he’s ever eaten, while at the same time feeling slightly disgusted with himself.

Towards the end, we have doughnuts, which Goldfinger’s nurses offer to his associates ahead of their raid on Fort Knox.

From stone crabs to doughnuts; from gourmet to junk. American food culture in a nutshell. But we can’t ignore Fleming’s own cultural context when considering his food choices. The crabs we can take as read; no doubt Fleming himself ate the meal during his visits to the country. The doughnuts seem at odds with the ‘Bondiverse’ or ‘Bondscape’ (take your pick), until you consider that for Fleming, doughnuts were a breakfast item, the American equivalent of Europe’s croissants or bread rolls.

England’s food culture is represented by Bond’s meal at the Grange, Goldfinger’s pile in Kent. Here he enjoys a dinner of shrimp curry, roast duck, and cheese soufflé. Like avocados and spaghetti Bolognese, the curry would have been exotic to Fleming’s original readers but has since been incorporated into the national cuisine. Although it’s considered that the first Indian restaurant was the Hindoostane Coffee House, which opened in London in 1810, and before then, the first curry recipes were circulating from the mid-18th century, curry houses were not established in any number in England until the 1950s following the arrival in Britain of Bangladeshi communities. Birmingham’s first Indian restaurant is thought to be John’s Café, which opened in 1954. Published in 1959, Goldfinger reflects the burgeoning interest in Indian food in Britain.

While we have the modern, in the form of curry, we also have the ancient. The placement of the soufflé at the end of the meal, though somewhat unusual now, is a nod to the tradition, particularly in Britain, of serving savoury food at the end of the meal, which, it’s claimed, is intended to cleanse the palette before drinking sweet or fortified wines. That would certainly explain the marrow bone with which M finishes his meal before ordering a brandy at Blades in Moonraker, the avocados that Bond eats in Casino Royale and Diamonds Are Forever, and the angels on horseback (oysters wrapped in bacon) in Dr No. These days, the tradition of the after-dinner savoury has declined, but it’s still hanging on, surviving largely with the still regular appearance of the cheese board on restaurants’ dessert menus.

And then there is the food of France. Ian Fleming never precisely acknowledges it, but it’s clear from his writing and experiences: he was a Francophile. He travelled to France pretty much every year, and, during his relationship with Monique Panchaud de Bottomes, would regularly drive through France to Geneva, taking the same route, in fact, that Bond himself follows in Goldfinger. Along the way, we are treated to the regional specialities of France: sole meunieure in Orleans, quenelles de brochet (pike dumplings) at the nearby Auberge de la Montespan, and choucroute garnie in Geneva (technically an Alsatian speciality, but close enough).

Again, for Fleming’s British readers, this would have been height of sophistication, even if they didn’t quite know what the dishes were. In France and Switzerland, though, was no more than good, honest fare. The inclusion of the dishes reflects Fleming’s own experiences, having the privilege to be widely travelled and engage in food tourism. The food also helps to cement the ‘when in Rome’ rule of Bond food choices: eat local.

This piece began life when I (David) sent Edward a message asking him what he considered to be the foodiest of the Bond novels. Not long afterwards, he sent me his ‘thoughts’ (the article above), which I thought were too good not to share.

Licence to Queer (David) and Licence To Cook (Edward) meet in real life in the shadow of the Rock of Gibraltar!

All of the photographs of food are from Edward’s website, www.jamesbondfood.com. Those of the exhibition about Birmingham curry houses were taken by me (David), when I visited this excellent exhibition in 2018. The curator of this exhibition speaks about his work here: https://www.soulcityarts.com/project/knightsoftheraj/