From Dicky, with Love: Judging the Bond books by their covers

Richard Chopping’s striking covers for Fleming’s Bond books helped them to stand out, significantly contributing to their popularity. Chopping was a gay man who became one of the first people in the country to enter into a civil partnership. Jordan Welsh turns the pages on his extraordinary life.

If you ask anyone to identify an Essex link with James Bond, then some fans may refer to the film Goldfinger. In the 1964 film, Bond uses a tracker to follow Goldfinger to Southend Airport and then onto Switzerland. Back then Southend Airport was small but still one of London’s busiest airports. Film watchers will also note that in Goldfinger Southend-on-Sea is clearly displayed on Bond’s tracker display screen: Bond was well ahead of the curve by having an in-car navigation system long before it was popular! Stansted Airport, the other Essex airport that overtook Southend in terms of scale and passenger numbers, would also make an appearance in other Bond films.

But there is more to Essex than its airports.

It is a relatively rural county and that was even more true when Ian Fleming was writing the Bond novels in the fifties and sixties. The new towns of Harlow and Basildon in the south of the county were still in the early stages, the post-war housing developments in other towns that would change the landscape and the local population were only just starting to come to fruition.

Essex hardly seems to evoke the same excitement as the hustle of London, or Egypt, Las Vegas, or dare I say a rocket to the moon! However, it was in the riverside community of Wivenhoe, a short distance from the historic town of Colchester, which provides Bond with a further connection to Essex. The artist and author Richard “Dicky” Chopping is not always a name that gets fully appreciated with the international phenomena that is the James Bond franchise. During the early days of the novels, Chopping was one of key components as one of their longest serving book cover designers. Along with his long-term partner Denis Wirth-Miller (the two entered a civil partnership as soon as it became legally possible, in December 2005) they established a bohemian community on the banks of the River Colne, the influence of which can still be seen today.

Had history gone slightly differently then we might have an alternative story about Chopping to tell. One in which he might have become more well-known not for his Bond connection, but as an artist of wildlife, botany, and the natural world. So here is a short overview of Chopping’s life and career, as we take a closer look at the Bond covers.

Richard Chopping before Bond

Let’s start at the beginning: Chopping was born in Colchester, Essex in April 1917, spending his first year in a country still in the grips of the Great War. His father had come from a milling family and had done well as a businessman and store owner before later becoming the mayor of Colchester. The artistic flare of Chopping was apparent from a young age, a talent that was encouraged at Norfolk’s Gresham’s School where he was educated. Another creative mind, the gay composer Benjamin Britten, was a contemporary of Chopping at Gresham’s, as well as Donald Maclean who was a few years ahead. Maclean would later become a diplomat and a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring who passed government secrets onto the Soviet Union and eventually defected there in the fifties. The revelations surrounding the Cambridge Five shook the British establishment because of how widespread the infiltration was: one such spy Anthony Blunt had worked as the Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures from 1945-1972. These were spies at the very heart of major British institutions, passing details onto the Soviet Union, something that would not appear out of place in a Bond story (the controversy form’s the backbone of Fleming’s From Russia, with Love).

By the 1930s. Richard Chopping was attending the London Theatre Studio, before joining the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in rural Suffolk. The school was set up in 1937 run by Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines who had met and fallen in love almost twenty years prior and, following the return of Lett-Haines’ wife to her native America, the two men spent the rest of their lives together. Lucian Freud joined as a student in 1939, adding to the many recognisable names who honed their craft there. The East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing worked under an informal and free rein structure that allowed artists to fully explore their craft outside of the stuffy education given by other established institutions. As Jon Lys Turner commented, the art school was extremely popular with young men from London during the war because: ““It was almost like Fitzrovia in the country... They could get way from London and come and have a lovely time getting roaring drunk at this huge house.” This roaring drunk community in the middle of rural Suffolk seems an oddity, but it was a bohemian lifestyle that appealed to many. It was both informative and anarchic in equal measure.

This education was significant for Chopping for several reasons: it allowed for an education directly from Morris himself, a great artist and plantsman, through observation and instruction in the school’s immaculately kept gardens. It was also a bohemian community that would end up being replicated when Chopping returned to his native Essex and was certainly one of the early non-heteronormative environments that appeared to be quite open and inviting. Morris and Lett-Haines were open in their relationship, with Morris having had affairs with the artists John Aldridge and Paul Odo Cross, while Lett-Haines had been in relationships with Stella Hamilton and Kathleen Hale.

Morris’ garden would provide the greatest inspiration for Chopping with wildlife and plants featuring frequently in a lot of his work. The garden itself became a fascinating attraction. The writer Vita Sackville-West, who had several lovers of different genders, was a regular visitor and grew some of Morris’ irises in her garden at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent. As well as Beth Chatto, who established her own garden in Elmstead Market a few miles from Wivenhoe, which is still today a tourist attraction.

By the 1940s, Chopping was working on natural history and children’s books. His wonderfully detailed illustrations adorned the pages of Butterflies in Britain (1943), A Book of Birds (1944) and Wild Flowers (1944). A collaboration with his partner Denis Wirth-Miller saw the publication of Heads, Bodies and Legs (1946), a quirky flipbook aimed at children following the tradition of allowing the head, body, and legs of a figure to be changed to create bizarre looking people.

In the late 1940s, Chopping’s skills in drawing the natural world were due to be put to good use as he was commissioned to contribute drawings to an ambitious Penguin series on British wildflowers, which was likely to have reached 22 volumes in total. At the last minute the publisher, concerned about the costs of such a series, decided to pull it from publication in its entirety. It clearly would have been an astonishing collection and probably would have been highly acclaimed, making Chopping a household name in the genre.

Wivenhoe and Chopping

By the early 1940s, Chopping and Wirth-Miller were interested in settling down and Wivenhoe, near to Chopping’s childhood town of historic Colchester, seemed ideal. Located on the banks of the River Colne, Wivenhoe had for centuries seen its stretch of the river filled with boats coming and going to the docks in the Hythe area of Colchester and several boat repair and building facilities in Wivenhoe itself. Chopping and Wirth-Miller purchased a waterfront property called the Storehouse, which was in dire need of refurbishment, however the move was put on hold due to the heavy military presence in the area. Colchester itself is a garrison town, and Wivenhoe (along with the village of Rowhedge on the opposite of the River Colne where the Chopping family owned a mill) was seen as important due to its boatyards and proximity to the North Sea.

Further complications occurred in 1944 when Denis Wirth-Miller was arrested and found guilty of gross indecency, a term that for all its vagueness could be applied to several different acts which could well be seemingly harmless but nonetheless elicited suspicion and concern. Homosexuals were hit particularly hard by laws surrounding gross indecency including the buggery act and the criminal law amendment act of 1885, the latter of which made any male homosexual act illegal and removed the need for any witnesses. The ambiguity of these laws made it difficult for anyone to get a fair trial with high profile figures such as Oscar Wilde and Alan Turing unfortunately becoming tangled up in a system that ostracised and victimised them.

Jon Lys Turner in his book The Visitors' Book: In Francis Bacon's Shadow: The Lives of Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller notes how the area that Wirth-Miller was caught in had a reputation for illicit acts between men. Wirth-Miller always maintained that he had been caught simply doing up his fly, however the odds were stacked against him. As a conscientious objector in war time and being of German ancestry his story was not believed and he was sent to prison at Wormwood Scrubs until January 1945. The difficulty came in trying to maintain contact between Chopping on the outside and Wirth-Miller in prison. Their letters had to remain extremely coded to prevent any interceptor clocking the true extent of their relationship. Such a revelation would have provided the proof for a longer sentence for Wirth-Miller and could well have seen Chopping imprisoned too.

In 1945, Chopping and Wirth-Miller were allowed to move into their home, where they continued to live together for over fifty years. By the 1950s, the waterfront at Wivenhoe was in decline as the ship trade withdrew, mainly due to the bigger and larger ships being unable to navigate this tidal and shallow area of the River Colne. This slightly “shaggy around the edges” vibe was in many ways what Chopping and Wirth-Miller wanted: a sense of faded grandeur in which their bohemian community could exist without borders and controls.

Wivenhoe soon become visited by a number of well-known and influential figures, and soon this rural waterfront community developed into a growing artistic group, similar to those seen in London and Suffolk that Chopping and Wirth-Miller had been a part of. It offered a freedom and openness that could not be found elsewhere, as well as a gorgeous landscape that inspired many, particularly Wirth-Miller. Wivenhoe’s direct train service to London also appealed in making the journey easily accessible to those city-based friends.

Chopping and Wirth-Miller were known for their generous hospitality and exciting adventures. Their relationship could be quite volatile with fights and arguments becoming public spectacles. Alcohol was drunk in large quantities, but the conversation about art and literature flowed just as liberally between the hosts and their guests.

The artist Francis Bacon (1909-1992) was a regular visitor to Wivenhoe to see Chopping and Wirth-Miller. Bacon often turned up unannounced, sometimes drunk, and sometimes making a lot of noise. They had initially established a friendship as young artists in the late 1930s. Despite being a lover of the city, Bacon enjoyed Wivenhoe and its beauty so much so that he later purchased a house in 68 Queens Road to have a base and studio for spending time outside of London. Queens Road is an unassuming street lined with Victorian terrace houses that were originally built for the workers of the boatyards.

Bacon spent a good deal of money in refurbishing the property, but ironically used it very little, instead using a studio at the Storehouse and reportedly disliking the fact that he had to climb a short hill and cross over a railway line to get to his newly purchased property. Bacon lived there with the photographer John Deakin in the fifties, although his time there became infrequent during the late sixties following Deakin’s death. It was said that following Bacon’s death the house remained pretty much as he left it, becoming a shrine to his memory that was overseen by Chopping and Wirth-Miller who maintained ownership of the property.

Bacon along with Wirth-Miller frequently visited the pubs around Wivenhoe, earning a reputation for themselves. In 1977, Bacon was the star guest at an exhibition at the Wivenhoe Art Club which included works by Wirth-Miller. A drunk Bacon gave horrific remarks about the art works. Bacon was subsequently banned from the Wivenhoe Art Club, something that was probably retrospectively enjoyed by the local artistic community.

The actress Joan Hickson was a nearby neighbour in Wivenhoe from 1958 where she lived for forty years until her death in 1998. Hickson is probably best known for playing the role of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple in the BBC television series that ran from 1984-1992. Chopping and Wirth-Miller were invited for drinks on a few occasions, however I imagine Hickson’s gatherings were more conservative than their raucous parties.

Martin Newell in his book “A Prospect of Wivenhoe” ponders whether Wivenhoe has a gay community. His conclusion is that it doesn’t have one any more than it has a heterosexual community: Wivenhoe simply has a community. It has a community that has gone through a great deal of change over the last eighty years, but still embodies some of those attributes that Chopping and Wirth-Miller helped to establish there. A community too in which Chopping’s iconic Bond covers were created.

Bond and Chopping

Chopping first became associated with the Fleming family via Ann Fleming (Ian Fleming’s wife) who had attended one of Chopping’s art exhibitions in London in 1956. Chopping was part of a three-man exhibition in which he was exhibiting his signature artistic style, the trompe l’œil. In a review entitled ‘Present-Day Romantics’ The Times praised Chopping stating “he is using the ambiguities of his technique to convey allegory on the maturing of human wisdom in exactly the same spirit as the Dutch flower painters.” (Quote taken from Jon Lys Turner’s book)

It was Bacon who had insisted that Ann Fleming be given a private tour and believed that it would do Chopping a world of good. Ann would later go to her husband and in a few months a meeting was set up. Of that meeting, Chopping wrote “Fleming himself opened the door immediately ushered me upstairs to his study… he said, as if I had appeared by chance: ‘You are just the man I wanted see!’” (Quote taken from Jon Lys Turner’s book)

Fleming had felt that the growing success of the Bond novels required the books themselves to have better and more striking covers. The first four novels had sold well, with the latest book Diamonds Are Forever selling out its first publication run in 1956.

The commission was to design the jacket for the next novel From Russia, with Love, thus beginning Chopping’s connection with the world of James Bond. Reputedly, the cover design opportunity had original been offered to Lucian Freud. Freud enjoyed a complicated but at times close friendship with Francis Bacon, although Chopping apparently was not much of a fan of Freud with his diaries and letters reflecting little admiration for Freud’s art. Freud himself would visit Chopping’s home in Wivenhoe in rare, fleeting trips to see Bacon.

Chopping’s jacket cover design for From Russia, with Love (the fifth book in the Bond Series) appeared in 1957 and would lead to Chopping being commissioned to design the covers of another eight Bond novels by Fleming, plus the cover of the series continuation Licence Renewed (1981) written by John Gardner, which helped to add an element of continuity between Fleming’s and Gardner’s novels. From Russia, with Love received mostly positive reviews, with sales being strong especially after John F. Kennedy included it as one of his favourite books. Additionally, interest was high after the British Prime Minister Anthony Eden spent time at Fleming’s Goldeneye estate in Jamaica following Eden’s health problems after the Suez Crisis.

Chopping was paid well for the design, although received no royalties from the book sales, with Fleming owning the original copy of the cover design, something Chopping regretted. In subsequent cover designs, Chopping upped his fee which Fleming and the publisher Jonathan Cape were more than happy to pay owing to the continued success of the series.

The idea and design for the cover of From Russia, with Love is normally credited to Fleming himself, although Chopping disputed the fact that the cover was entirely of Fleming’s design. Although Fleming suggested what the cover should look like, it was Chopping who would bring it to life. Fleming’s expectations were high, and his list of demands for the cover were long, including the stipulation that no gap be left for the title or author’s name. According to Chopping, Fleming, “wanted everything except the kitchen sink to illustrate the overall straightforward message of a murder done with a gun.” (Quote taken from Jon Lys Turner’s book)

The gun used for the cover was a .38 Smith and Wesson revolver (Fleming’s own gun in some iterations of the story), which came as the result of criticism from Geoffrey Boothroyd who noted that Bond’s gun in earlier novels was a .25 Beretta or “a lady’s gun” to use Boothroyd’s own words. Fleming was thankful for Boothroyd’s comments and changed Bond’s type of gun in the novels that followed From Russia, with Love. Chopping’s drawing of a .38 revolver signalled the start of Bond’s journey with a more ‘manly’ weapon, even if such a gun would not feature until the following novel.

The design for From Russia, with Love was typical of the trompe-l’œil style that Chopping employed. Trompe-l'œil means to ‘deceive the eye’ and uses imagery to create the optical illusion that the objects shown in the picture are seen as three dimensional. This sort of visual trickery is a wonderful form of deception which would not feel out of place in a Bond story: the art of making someone think one thing when it was not true, an artistic magic trick as it were, and an effective one at that.

Think how Wile E. Coyote uses paintings of tunnels on rocks to try and deceive Road Runner in the Looney Tunes cartoons, or how the two spies in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (loosely based on the 1964 novel by Ian Fleming) also use a fake tunnel picture to attempt to trap the much sort after car. Suddenly you start to see how trompe-l’œil appears throughout numerous mediums across the centuries.

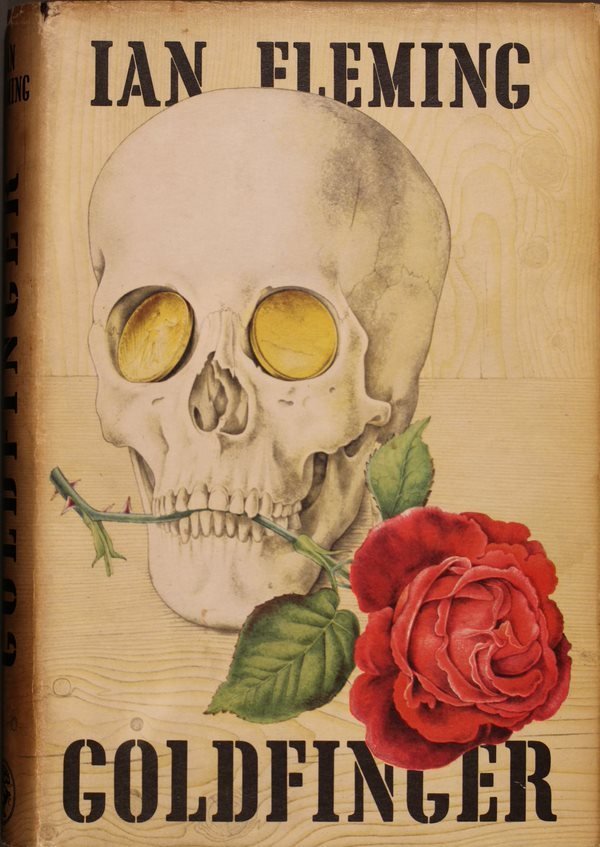

The next novel Dr. No (1958) did not feature a cover by Chopping. His next commission would be for Goldfinger (1959) which featured a rose between the teeth of a skull: Chopping declared this to be his favourite cover. This was followed by the short story collection For Your Eyes Only (1960) which featured one of Chopping’s trademark detailed close-ups of a human eye.

Thunderball (1961) saw a skeleton hand over the Queen of Diamonds and a dagger between its fingers. The Spy Who Loved Me (1962) depicted a commando knife supposedly based on one owned by Fleming’s editor, whilst On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963) featured a more subdued cover of a pair of hands drawing the Bond family coat of arms. You Only Life Twice (1964) saw Chopping return to his wildlife drawing background by featuring a toad with a dragonfly under one of its feet and a large pink flower dominating the top half of the cover.

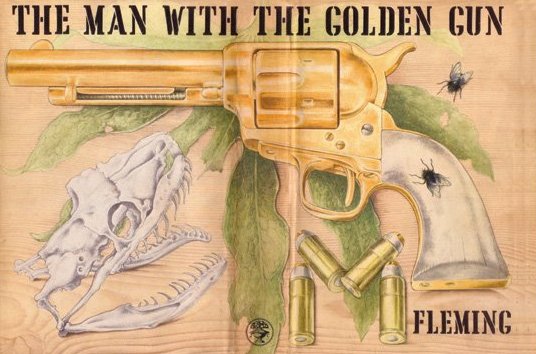

The nature theme continued in The Man with the Golden Gun (1965) which showed the handle of the infamous golden gun, some bullets, and two flies which are seemingly out of place in the context of the cover itself.

Chopping’s trademark flies returned in the short story collection Octopussy and The Living Daylights (1966) which depicted a seashell and a fish surrounded by many pesky flies.

The covers designed by Chopping were certainly an eclectic mix, depicting both aspects of the story and Chopping’s own interests and skills, particularly in drawing elements of the natural world. Essentially this achieved what Fleming had been hoping for: covers that were in themselves iconic and instantly recognisable. There is no denying how unique and eye catching these covers must have been on publication and how far removed they are from the posters that would come to advertise the film adaptations. The covers certainly contributed to the success of the novels and blended violence and spying with the natural world that Chopping sourced from the Essex countryside.

Chopping after Bond

Chopping’s career was not wholly focused on the James Bond books. In fact, by the 1970s he was beginning to distance himself from the series and criticised their violence. Both Chopping and Wirth-Miller were pacificists, and Chopping was not comfortable with the weaponry that he was being asked to draw. In many cases he had been sent guns in the post to draw them as accurately as possible. The prospect of having guns in the house unnerved Chopping, as did any depiction of violence that seemed to glamourise its usage. In Jon Lys Tuner’s book, there is a story in which Fleming supposedly played pranks on Chopping by claiming that the police were suspicious of him after discovering that Chopping was in possession of a gun like one used in an unsolved murder case. If true, it was a harsh and dark trick to play on someone who clearly was not happy with having weapons in his home.

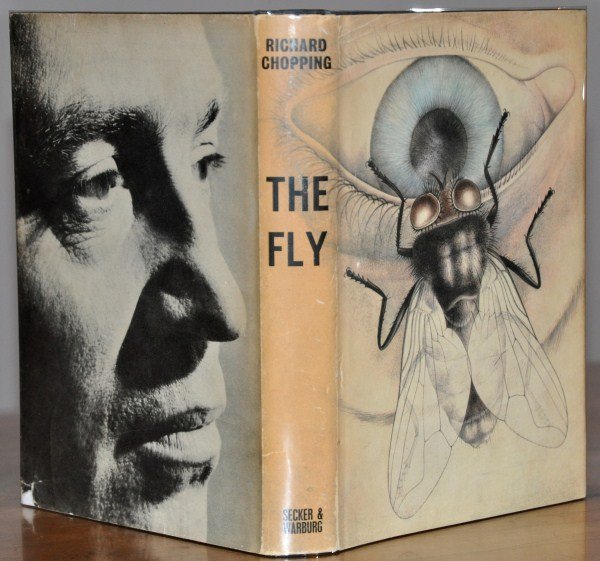

Already an accomplished painter, Chopping had turned his attention to other creative works. Throughout the 1940s, he produced several books on natural history as well as children’s stories, some of which had been illustrated by his partner Denis Wirth-Miller. However, in 1965, he produced his first novel around the time of the growing excitement of the early Bond films. The Fly was an exploration of depravity and lust, all witnessed from the perspective of a voyeuristic fly. It was a shocking book and often criticised for being unpleasant and focussing on the worst sort of people in society… yet it was a hit!

The cover too seemed equally unnerving, in that it depicted Chopping’s great care for detail by showing a fly (highlighting his natural science interests) that has landed on an open human eye. Flies of course featured heavily on a number of Bond book covers, as did human eyes and skeletons.

This was followed by another novel, The Ring (1967) which focuses on a gay man’s relationship with various people in his life, including his aging mother. It was certainly a bold move to produce a novel that in many ways tried to humanise gay men and place them at the centre of the story. At its heart was a story of love and desire that was previously viewed as unacceptable in society, and it certainly portrayed the darker elements of this love-seeking. Its cover included the familiar eye and fly trademark, along with a large rose dominating the page. The Ring was not well received, driven by its controversial subject matter and concerns about the repeated crotch motifs and emphasis on the penis.

Chopping and Wirth-Miller had been together for almost seven decades, and although their arguments and fallings out could be notoriously volatile, in 2005 they registered a Civil Partnership in Colchester, becoming the first couple to do so in the area. Chopping was eighty-eight and Wirth-Miller was ninety at the time. Both had experienced life under which homosexuality was a crime, through to its partial decriminalisation in 1967 and the gradual shift towards more acceptance and equality. In later life they were constantly batting away requests for interviews in relation to their connection with Bacon and Fleming, something Chopping and Wirth-Miller resented as it pigeonholed them as merely characters in other people’s stories.

Chopping died in April 2008, whilst Wirth-Miller died a few years later in October 2010.

In recent years there has been the glimmer of a return of interest in Chopping’s work: to mark the centenary of Fleming’s birth the Royal Mail issued commemorative stamps featuring some of Chopping’s designs. An exhibition of some of the first edition covers was held at the Barbican in London and another titled “Richard Chopping: The Original Bond Artist” was held at Salisbury Museum in 2021. Running from December 2021 until 18th April 2022, the Firstsite Art Gallery in Colchester will host a free exhibition on some of the iconic artists who studied at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing, where Chopping and Wirth-Miller had both studied.

The old, well-oiled phrase has it that you should not judge a book by its cover. For the most part this is true, especially in relation to people and places. However, in the publishing industry, a book cover can hold a lot of power. It can be used as an effective marketing tool. It can set the tone of a book: light colours would symbolise a more uplifting book, while a darker palette would represent something at the opposite end of the spectrum. In some cases, a book cover can become just as iconic and recognisable as the story itself.

Richard Chopping’s designs for the Bond novels in the fifties and sixties certainly added a strong visual presence to the books just before the Sean Connery films captured the public’s imagination. As much as readers were buying Fleming’s stories, it was Chopping’s jacket cover designs that they first encountered. Although Chopping tried to distance himself from the Bond series in his later years, with his name often missing from the conversations surrounding the books, he undoubtably helped them to grow.

One of the few comprehensive books on Chopping, is the one which I have referred to throughout: Jon Lys Turner’s The Visitors’ Book, or the give it it’s full title The Visitors’ Book, In Francis Bacon’s Shadow: The Lives of Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller. The title quite simply sums up part of the issue of Chopping’s career, in that he is viewed in the shadow of someone else. Both Francis Bacon and Ian Fleming were the headline grabbing names who existed at forefront, whilst Richard Chopping was seemingly in the background. Quite rightly, Turner’s book links Chopping and Wirth-Miller not just as romantic partners, but also as artistic collaborators and mutual supporters.

Chopping’s was a life of highs and lows and “what ifs”. Yet his unique and iconic eye for detail allowed his work to stand out, and certainly captured the attention of many. Chopping should be partly credited for the growing the appeal of the Bond novels because he helped to establish a recognisable visual identity. As a result of Chopping, a quiet waterfront town in Essex saw an artistic community develop, and it was here that those incredible Bond covers had their origin.

Jordan Welsh is a literature PhD student at the University of Essex where he is interested in the Romantics and Victorians, as well as representations of nature, religion, and the body. He lives in Essex and is passionate in talking about its history and heritage.

You may also be interested in these articles written by another Chopping aficionado, Ben Williams:

https://literary007.com/2014/05/31/richard-choppings-influence-on-popular-culture/

https://literary007.com/2013/10/05/field-report-ben-williams-from-mi6-confidential/