Fleming’s faggots, gays and queers

'In my profession,' said Bond prosily, 'the exact meaning of words is vital.’ (On Her Majesty's Secret Service)

As a Bond fan with a degree in linguistics I couldn’t agree more. New readers of Fleming’s Bond novels may be surprised to read words which have shifted in meaning since Ian Fleming used them in the 1950s and early 1960s, particularly words associated with homosexuality: ‘faggot’, ‘gay’ and ‘queer’. Many are quick to dismiss them as relics of an earlier age. But when we look at these words in context, it becomes apparent that Fleming might have been fully aware of what he was doing all along…

When I first read the Bond books as a child I knew full well that there was something ‘different’ about me. And even if I wasn’t ready to apply the label ‘gay’ to myself, that didn’t stop the playground bullies. Mind you, most things were ‘gay’ when I was growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, even if they had no romantic interest in people of the same sex. Things that were ‘gay’ included a rubbish pair of trainers (Hi-Tec was the brand most guaranteed to get you bullied in my school). Even geography homework was ‘gay’ according to some people in my class, those who didn’t share my passion for working out six figure grid references.

Using ‘gay’ as an adjective to describe something that was rubbish was recorded in some American distionaries as early as 1978 but not recorded with this new meaning in the Oxford English Dictionary until 2003. As usual, dictionaries lag behind society. Understandably, people who compile dictionaries (lexicographers) like to wait to see if a word has staying power before recording it (a process called ‘codifying’). We should therefore be cautious when using a dictionary to judge how meanings have changed over time. It’s a good idea to shave several years off the date given as first recorded written usage as it was almost certainly in popular verbal usage well before then. This is doubly the case for taboo terms as people are often reluctant to write them down.

I have it on good authority (my own) that ‘gay’ was being used a slur in British playgrounds in the late 1980s, at least fifteen years before it was codified in the Oxford English Dictionary. It took a long time for guardians of the written word to cotton on to the ‘gay’ = rubbish meaning. A 2002 article in The Independent expressed surprise at the phenomenon, one of the first written uses of the word in a ‘reliable’ source.

Growing up, reading was my escape from feeling rubbish most of the time and I read anything I could get my hands on. I came across the word ‘gay’ very frequently, in part because of my predilection for fiction written in the middle of the 20th Century - in addition to Fleming I read a lot of Roald Dahl and Enid Blyton, all authors who have had the label ‘problematic’ applied to them in recent years, usually because of their treatment of race, sex and gender, less so sexual orientation.

These authors seemed to be unambiguously using the word ‘gay’ in the sense of ‘happy’ or ‘bright’, a meaning that dates back to the first decade of the 14th Century. Even so, every time I came across this word I cringed. Every time it flashed off the page, like it was written in neon. Even if I tried to skim past ‘gay’ it would threaten to suck me in, like a whirlpool dragging a ship inexorably down, down, down.

The only thing I could do to extricate myself was to rationalise it: the authors were not writing about me. They weren’t even talking about homosexuals. They were using ‘gay’ to mean ‘happy’ or ‘bright’. Move on David.

It’s only years later, as an out and proud gay man, that I found the courage to slow down whenever I came across the word ‘gay’ and examine its usage in context. What I found sometimes surprised me. Although I’d previously been content to write off Fleming’s use of ‘gay’ as archaic, now I wasn’t so sure.

The frequency with which Fleming uses the word ‘gay’ in his novels varies considerably. Here is each title presented in chronological publication order alongside the number of times they feature the word 'gay’. I have not included the two collections of short stories because the individual stories were written at different times across Fleming’s Bond output from 1952 until 1965:

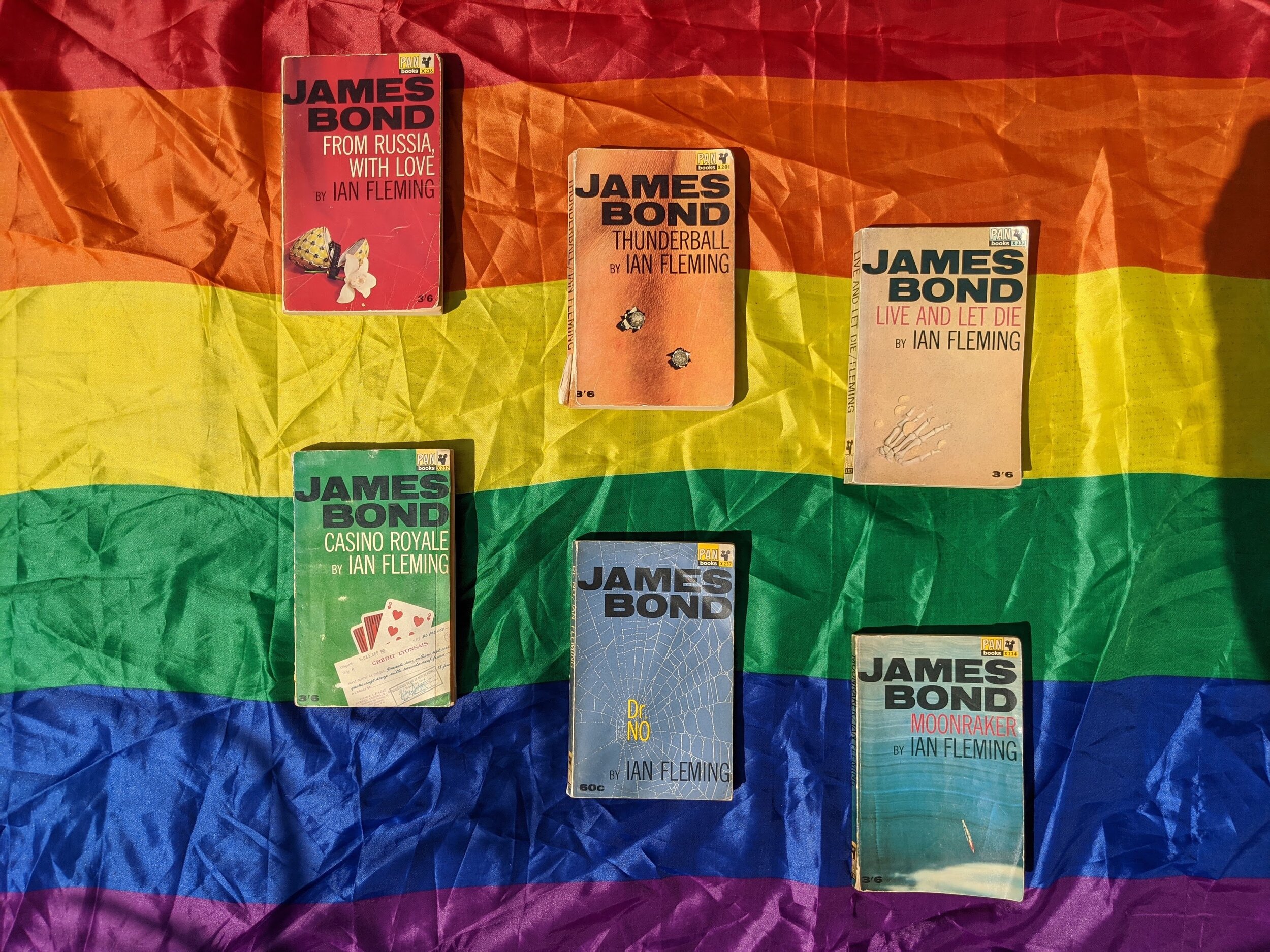

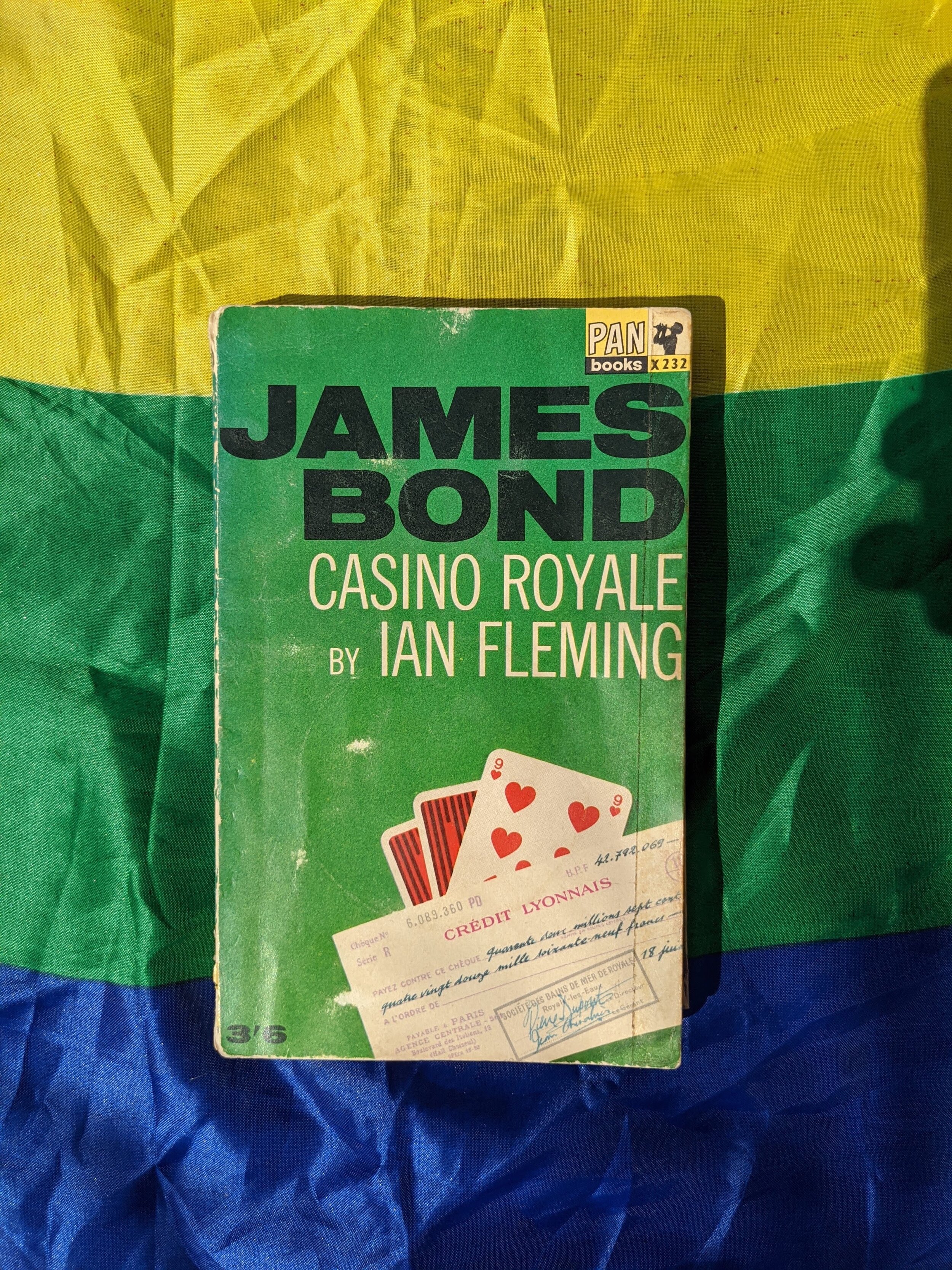

Casino Royale - 8

Live and Let Die - 1

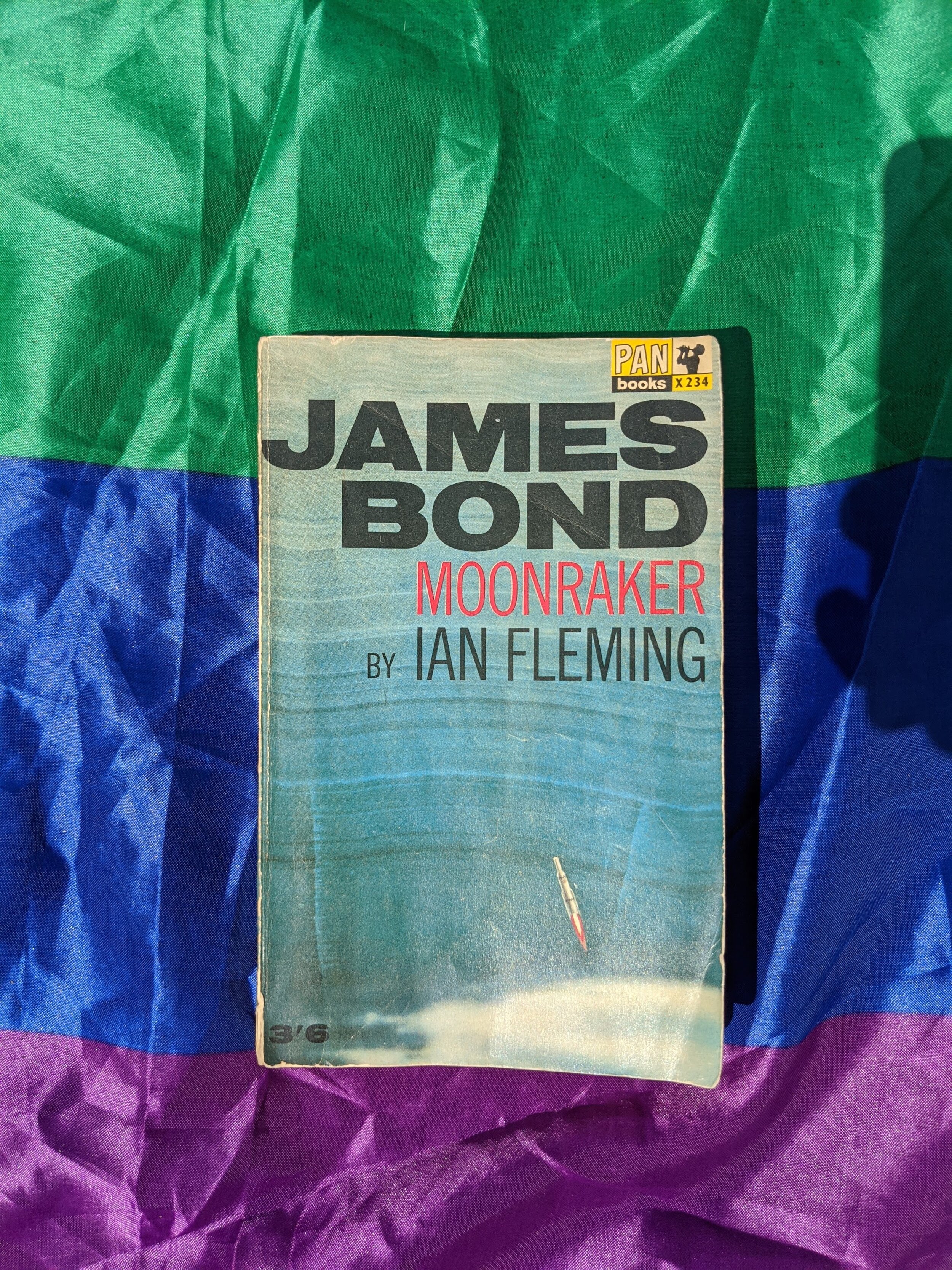

Moonraker - 1

Diamonds Are Forever - 1

From Russia, With Love - 6

Dr No - 1

Goldfinger - 0

Thunderball - 9

The Spy Who Loved Me - 5

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service - 12

You Only Live Twice - 2

The Man With The Golden Gun - 1

I expected there to be a clearer pattern, with Fleming using ‘gay’ with decreasing frequency as the language changed around him. Although some claim ‘gay’ was not widely in use as a way to describe a homosexual until the late 1960s, it was recorded with this meaning in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1935, which means it was in use well before this! For a time, the two meanings co-existed until the earlier use (happy/bright) was superceded.

It’s therefore impossible that Fleming was unaware of the newer ‘homosexual’ meaning. One might argue that, traditionalist as he was in many ways, he perhaps eschewed using what he saw as a slang term and clung to the old way of using the word. Even so, there is evidence in the texts, as early as 1953’s Casino Royale, that he was using ‘gay’ in both its new and old sense - and sometimes both at the same time.

Here are the eight occasions he uses ‘gay’ in Casino Royale:

Chapter 5

Even the small town and the vieux-port managed to fix welcoming smiles across their ravaged faces, and the main street became gay with the 'vitrines' of great Paris jewellers and couturiers.

Chapter 8

Bond had chosen a table in one of the mirrored alcoves at the back of the great room. These had survived from Edwardian days and they were secluded and gay in white and gilt.

Chapter 13

The spatula flicked the two pink cards over on their backs. The gay red queens smiled up at the lights.

Chapter 22

Bond loved the place [the restaurant Vesper has chosen] at first sight — the terrace leading almost to the high-tide mark, the low two-storied house with gay brick-red awnings over the windows, and the crescent-shaped bay of blue water and golden sand. (Chapter 22)

Chapter 26:

That night she made a special effort to be gay. She drank a lot, and when they went upstairs she led him into her bedroom and made passionate love to him.

That evening most of the gayness and intimacy of their first night came back.

'I do believe I'm tight,' she said. 'How disgraceful! Please, James, don't be ashamed of me. I do so want to be gay. And I am gay.'

While the first three uses are fairly unambiguously used to mean happy/bright, as the novel progresses and Fleming seeks to create a sense of foreboding around Vesper, he uses the word with increasing frequency. First he uses it to describe the restaurant she has chosen during their holiday away, while Bond is recovering from his carpet-beating at the hands of Le Chiffre. And then in the penultimate chapter, just before Vesper is revealed as a traitor, Fleming uses it four times to describe Vesper directly or her relationship with Bond, a relationship founded on a lie.

Does Fleming draw attention to the word ‘gay’ to hint there there is something different about Vesper?

Even those who think 1953 was too early for writers to be intentionally provoking their audiences by using ‘gay’ in its newer sense, might pause for thought at this extract from a decade later.

1963’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service uses ‘gay’ more than any other Bond book. In this section, Bond is posing as the homosexual Sir Hilary Bray and is speaking to the lesbian-coded Irma Bunt about the meaning of her name:

'In my profession,' said Bond prosily, 'the exact meaning of words is vital. Now, before we met for cocktails, it amused me to look up your surname, Bunt, in my books of reference. What I found, Fräulein, was most interesting. Bunt, it seems, is German for "gay", "happy".

Is Bond trying to rile Bunt by pointing out that he’s aware that she’s a lesbian? I think so.

Fleming uses the word ‘gay’ almost exclusively to describe women or effeminate men and often when writing from a woman’s POV, either in the third person (From Russia, With Love) or first person (The Spy Who Loved Me). He’s certainly aware of the feminine connotations of ‘gay’.

Many of the words used to describe gay men play on the stereotype that gay men are less ‘manly’ and more woman-like. This is especially the case with ‘faggot’, which is arguably the most offensive word a person who isn’t queer can use to describe a gay person.

The word faggot has one of the weirdest histories (etymologies) of any word in the English language. In short: a faggot is a bundle of sticks tied together. It’s had this meaning since the 1300s. Then things get a bit more complicated, with two possible etymologies:

Because spinsters used to eke out a living by collecting together sticks into bundles and selling them to people to be used as fuel, faggot became associated with lower class or outcast women. This then became ‘extended’ as a euphemism to refer to homosexual men.

During the Spanish (and other) Inquisitions, people who opposed the Catholic church were routinely burned at the stake. They were made to collect a faggot which was then set alight. So essentially they made the fuel for the fire than killed them. Nice. The only alternative to being burned alive was to spend the rest of your life wearing a badge in the shape of a faggot, to show everyone you were an oucast. Faggot started to be used as a term for anything which is difficult to bear, similar to how ‘gay’ has been used since the 1980s.

Faggot appears only once in the Bond novels. Perhaps this is because ‘faggot’, although less well-known in the ‘homosexual’ sense in Britain, was being used in this way in the United States from the beginning of the 20th Century. Fleming was desperate to court a US readership with his books so its interesting that he uses ‘faggot’ in the only novel to be set exclusively in Britain: Moonraker.

In this sequence, Bond has Drax on the backfoot as he questions the supposed Anglophile philanthropist about his highly suspect second in command.

"By the way, how long have you had Krebs?" He asked the question on an impulse. There was a moment's quiet in the room.

"Krebs?" repeated Drax thoughtfully. He walked over to his desk and sat down. He reached into his trouser pocket and pulled out a packet of his cork-tipped cigarettes. His blunt fingers scrabbled with its cellophane wrapping. He extracted a cigarette and stuffed it into his mouth under the fringe of his reddish moustache and lit it.

Bond was surprised. "I didn't realize one could smoke down here," he said, taking out his own case.

Drax's cigarette, a tiny white faggot in the middle of the big red face, waggled up and down as he answered without taking it out of his mouth. "Quite all right in here," he said. "These rooms are air-tight. Doors lined with rubber. Separate ventilation. Have to keep the workshops and generators separate from the shaft and anyway," his lips grinned round the cigarette, "I have to be able to smoke."

The scene appears almost exactly midway through Moonraker, shortly before Drax is unmasked as a Nazi intent on destroying London as revenge for losing the Second World War. Curiously, Drax smokes cigars throughout most of the novel, so why does Fleming have him smoking a “tiny white faggot” of a cigarette in this pivotal scene? Is this to underscore Drax’s weakness, his effeminacy perhaps? He certainly behaves very nervously around Bond. Although Bond, at this point, still believes Drax is a patriot, I believe this is Fleming telling the audience to be wary. Drax is not all he seems.

Are such moments homophobic? I’m never entirely sure about this one. Fleming definitely had his fair share of views which we find unpalatable today, some of which he puts into the mouth of Bond. But Fleming also had a plethora of gay friends, including many exiles from sexually repressed Britain.

Just because someone says “I have gay friends” doesn’t give them a gay-friendly pass of course. But I believe Fleming was intentionally needling his audience back home in Britain and, inreasingly in the USA, by using words which carried queer meanings.

What about queer itself? Some in the queer community have been attempting to reclaim it since the 1980s. Only in the last few years has it become a widely (but not universally) accepted umbrella term for minority sexual orientation and gender identities. As a term I find it far more wieldly than the initialism LGBTQ+ and I attempt to normalise its use whenever I can (see the name of this website!). But I’m well aware it has been used to wound queer people attracted to the same sex since at least 1894, when the Marquis of Queensberry wrote a letter expressing his digust at the sexual relationship between his son and Oscar Wilde. More than half a century later, at the time that Fleming was writing Bond, the homosexual connotations of ‘queer’ were well known.

In the novels, ‘queer’ is used a lot more than ‘faggot’ but less than ‘gay’, appearing once, twice or three times in most of the novels until it suddently stops. The three final novels have no ‘queer’ at all. A sign that Fleming felt uncomfortable continuing to use it?

In earlier books it had been used variously to describe the villains, their lairs, Bond’s mission and even unconventional behaviours of the girls. In From Russia, With Love, Fleming uses ‘queer’ 3 times in quick succession to describe the distinctly unconventional Red Grant.

Perhaps because Thunderball was the first Bond novel I ever read from cover to cover, my favourite use of the word queer is Largo’s description of that novel’s nuclear physicist - and the scientific community as a whole.

Largo watched the thin figure shamble off along the deck. Scientists were queer fish. They saw nothing but science. Kotze couldn't visualize the risks that still had to be run. For him the turning of a few screws was the end of the job. For the rest of the time he would be a useless supercargo. It would be easier to get rid of him.

To Largo, Kotze is ‘queer’ because he’s not a man of action like his hypermasculine self. Although Largo is ‘other’ in lots of ways (his giant hands always amuse me), he is more ‘normal’ than Kotze.

But it’s all a spectrum.

Bond novels often feel like a ‘queer’ Cold War. Each character appears to be more ‘abnormal’ than the last. Many of the characters are grotesques, certainly alongside the comparatively ‘normal’ Bond. Even so, Fleming repeatedly has Bond reflect on his outsider status, an anxiety his creator felt keenly in his real life.

Many writers claim (including Young Bond maestro Charlie Higson) that all novelists can do when creating characters is to use the various different parts of themselves. I’m not saying Fleming was gay, or even ‘queer’ in the sense that’s been around since Oscar Wilde’s time and recently reclaimed. Just that Fleming understood the anxieties felt by outsiders. Even more so, he understood how his readers might feel anxious about the queerer parts of themselves (in the broadest sense). He armed himself with the words he needed to make his readers feel uncomfortable, deploying them with just the right frequency and precision to make them feel just the right amount of unease to keep them reading on.

So was Fleming using his audience’s homophobia to sell books? Very possibly. Does that mean we should just ignore, or even denounce, the Bond novels? Of course not. We should talk about them openly - their merits and their faults. And this includes queer readers, who have a very long history of reclaiming things used to harm them.