DO look now: The coming out of Vesper Lynd

Why is Casino Royale’s Vesper Lynd such a queer icon? Perhaps it’s because she does such a good job of keeping a secret, one she gets to reveal to the world on her own terms. But the original script shows that this wasn’t always the case…

There comes a point in many queer people’s lives that being in the closet means being on a permanent losing streak and enough really is enough. After playing our cards close to our chests for years, we decide that now is the time to put all our chips on being true to ourselves and hope the cards aren’t going to be stacked against us. All in.

When I first saw Casino Royale on its initial release in 2006 I was still in the closet (although I prefer to think of it as ‘under cover’). Not only did I relate to Bond’s battles with who he is (“you do what I do for too long and there won’t be any soul left to salvage”) but Vesper Lynd’s too.

I’m not alone: many queer people find her relatable. But why?

As I have already explored in my queer re-view of Casino Royale, it might be something to do with her first appearing on screen wearing (as Bond observes) “slightly masculine clothing” and finishing the film dead, in accordance with all-to-prevalent ‘bury the gays’ trope. But on further reflection, I think it’s what Vesper does between these points that confirms her status as a verifiable queer icon. In particular, it’s what she does in the film’s nuanced final act.

Much as I love Bond films, they often unravel slightly in their final stages. The story becomes looser and the characterisation sometimes gets lost amid the explosions.

Casino Royale is an exception. Everything is so finely tuned and calibrated to keep us hooked and leave us reeling.

It starts with a text message arriving.

It’s hard to remember a time when we all weren’t as hooked on our phones, but it was as recently as 2006. At the time of Casino Royale’s release, the first iPhone was still several months away. Even so, Tomorrow Never Dies aside, Casino Royale was the first Bond film where mobile phones took a starring role. Vesper spends more time on her phone than any other character in the series. It was especially conspicuous in 2006, perhaps less so today.

Vesper’s crucial act is to leave her omnipresent phone behind, allowing Bond to learn her secret. She does it on purpose. Vesper has had enough of living with her secret and she wants to be found out. The chips are down. How will Bond react?

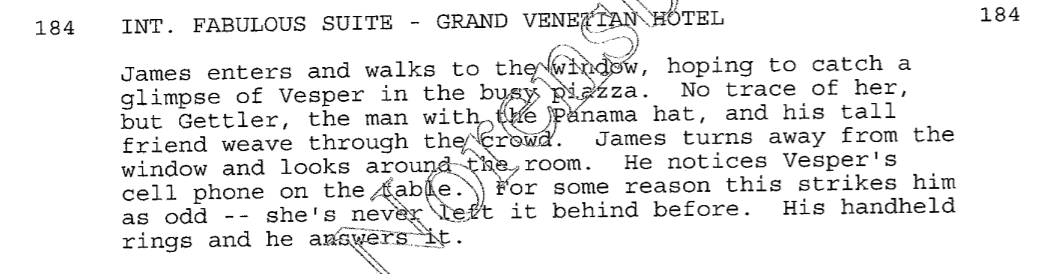

It seems that even the screenwriters were hedging their bets about this and it’s likely Bond’s response to being betrayed was still being worked out on set and even in the editing room. A heavily revised screenplay as late as November 2005 (the film started shooting in early January 2006) has Bond’s suspicions aroused by him sighting Gettler.

The sequence in the finished film is far more streamlined. It takes nothing away from Vesper’s agency, whose trustworthiness is not in question, at least until M drops her bombshell about the money not being deposited (the screenplay describes this as hitting Bond “like a sledgehammer”). In the film sequence, Bond picking up Vesper’s phone seems almost like a gesture of love rather than the actions of a distrustful partner. He’s midily curious at most, maybe concerned that she’s left it behind. Perhaps he might even run after her to make sure she has it?

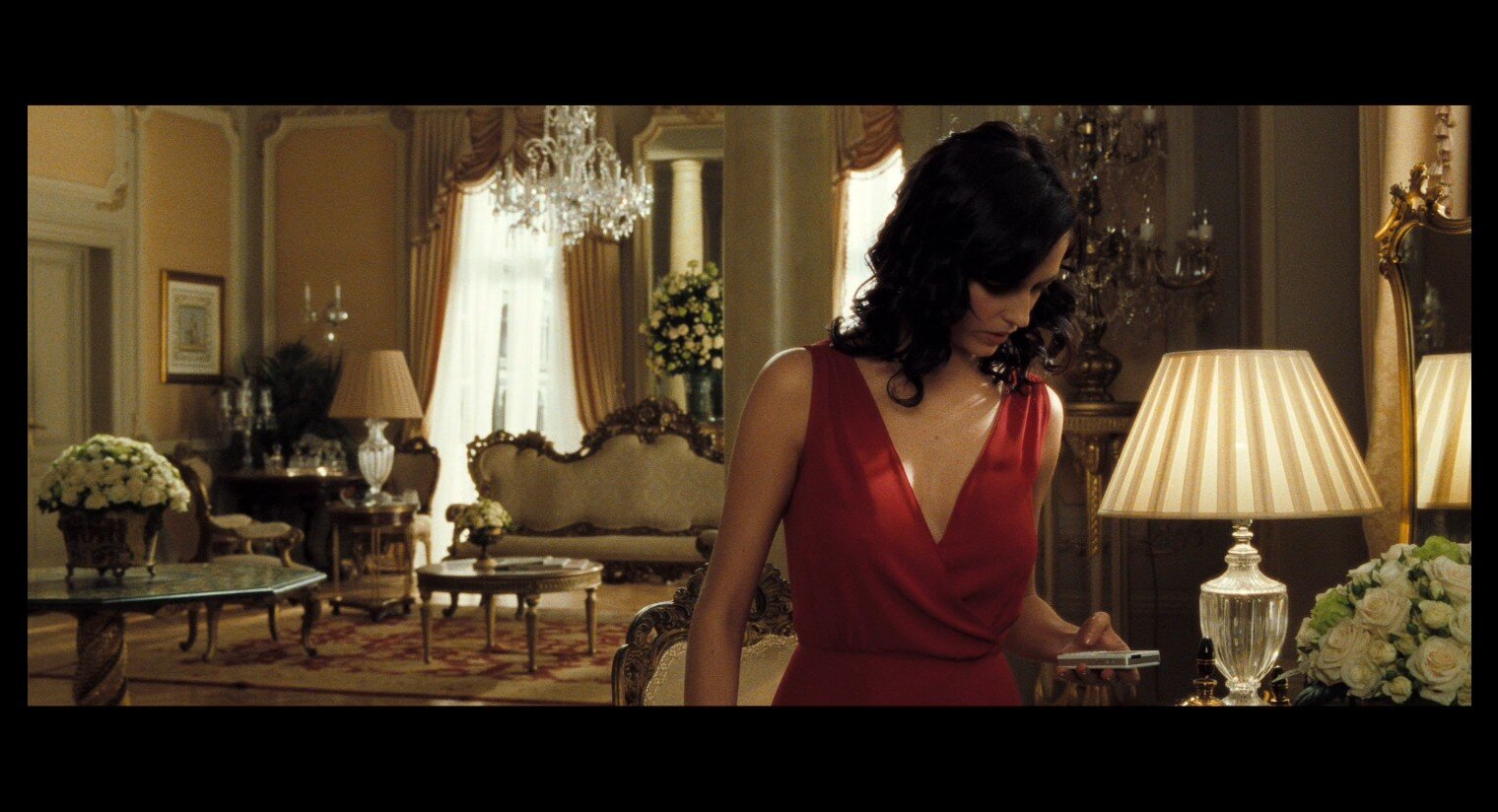

When Bond does give chase, Vesper makes it easy for him by wearing a bright red dress. Even this was up for debate in the drafts of the screenplay, the November 2005 edition referring to Vesper wearing both a “t-shirt” and, a few pages later, a “dress”, although the colour isn’t specified.

The red dress does triple duty. First of all, Bond doesn’t have to be the superspy he is to pick out Vesper in a crowd (the screenplay has him relying on hearing the click of her heels). Secondly, it helps us, the audience, track Eva Green’s figure through the grey, brown and green backways of labyrinthine Venice. Finally, it’s an homage to horror masterpiece Don’t Look Now directed by Nicolas Roeg (adapted from a novella by Daphne du Maurier who described her own same sex attraction as her ‘Venetian tendencies’). In Don’t Look Now, the main male character becomes fatally obsessed with a figure brightly dressed in red. Sound familiar?

But rather than Don’t Look Now, Vesper’s costuming tells us - and Bond - DO look now. She even turns around seconds before meeting Gettler to make sure Bond is following her, a moment missing from the screenplay and probably improvised while shooting.

This is it: the moment that makes me or breaks me. She knows how capable Bond is and, when he catches up with her, what will he decide?

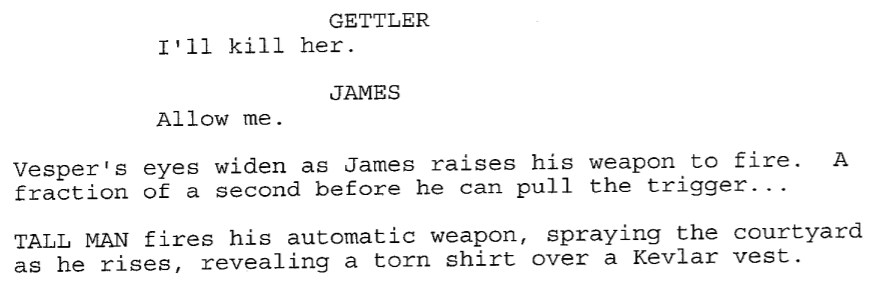

The screenplay has Bond announcing his intention to kill Vesper right to her face. He is only stopped from shooting her by a henchman springing back to life, taking the decision out of his hands for the time being.

The version in the finished film is far more effective. Taking cover in a pillar, Bond mutters his line (“Allow me”) into the shadows. It’s a private moment, not intended to be overheard. He’s still working things out. It makes Bond’s objective throughout the action sequence that follows nail-bitingly ambiguous. Is he going into the sinking house to kill Vesper or save her?

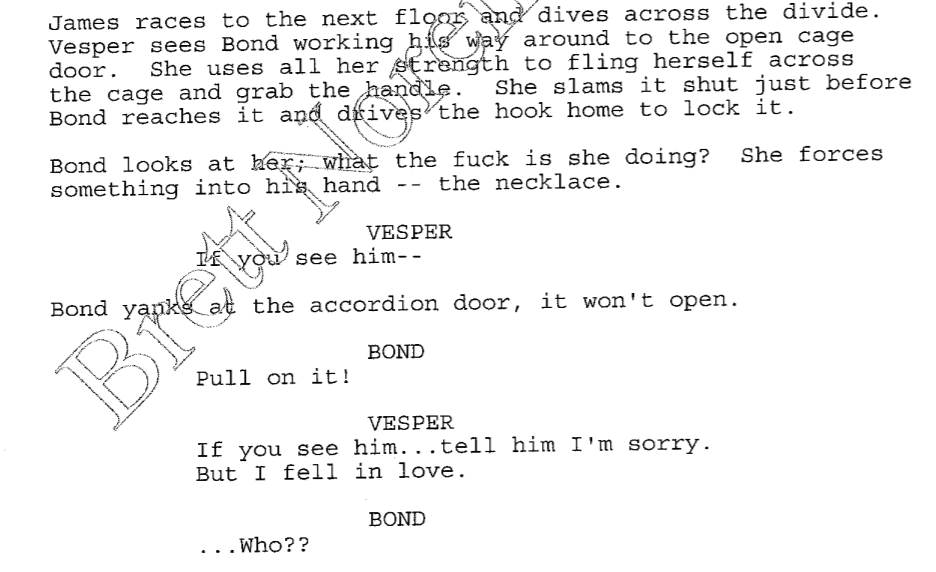

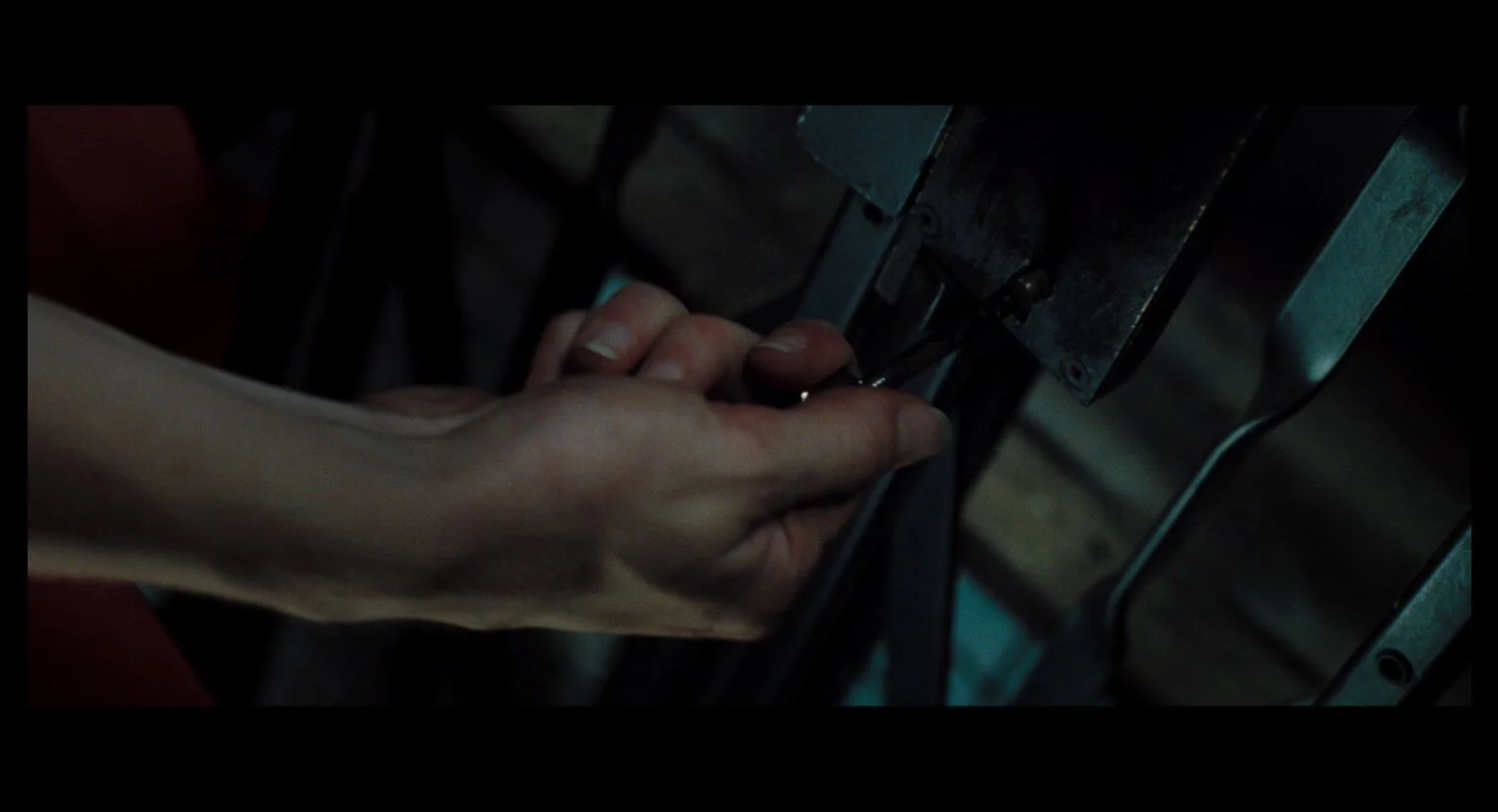

In the end, it’s Vesper who decides for him. The finished edit is shorn of anything that takes away from Vesper’s decision to end her own life on her own terms (the screenplay has some awkward business with the Algerian love knot necklace).

Is Bond angry here (“what the fuck is she doing?”) because he doesn’t get to finish the job? There’s no sense of this in the finished ending. He would do anything to get her back and, possibly, forgive her?

Perhaps if Vesper had a “tell” (she’s the only person without one according to Bond) she would have been discovered earlier and redeemed, like many other Bond girls. But the fact she was too good at keeping her secret is her real tragedy. When she chooses to come out, it is too late.

In real life, it’s never too late. Coming out should never be seen as a race. I am astonished at the confidence of some young people today, coming out while they are still in primary school. That would have been inconceivable for me. Conversely, some people come out much later in life, and some never come out at all. They might feel the odds won’t be in their favour, and they might be right. Not everyone’s coming out is a positive experience.

I am lucky: mine was, for the most part at least. When I look back it seems ridiculous that I was so worried. Like Vesper, I chose my time to come out and did it on my own terms. Not everyone is so fortunate.

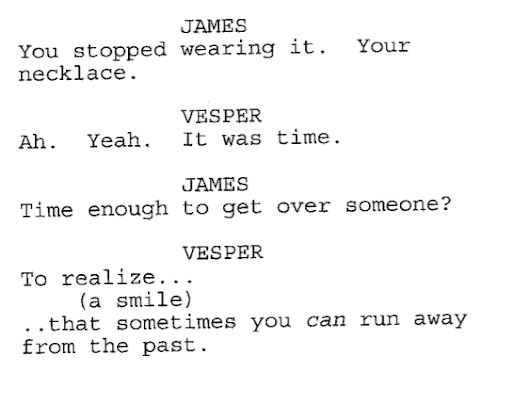

One of the final things Vesper says to Bond is “sometimes you can forget the past”. The original screenplay had it as “you can run away from the past”. Vesper is wrong in both versions: you can’t forget yourself and you can’t run away from yourself. Her tragedy is she cared too much about what Bond thought about her. If only she could have learned to love herself.

I discuss my own experiences with mental illness and suicidal thoughts in my queer re-view of You Only Live Twice where you will also find links to organistions that can help. James Bond films are fantasy, not reality. Whatever you do: talk to someone. Don’t keep it inside.

Screen captures are my own (usual copyright applies, see bottom of the screen). Production stills taken from https://www.thunderballs.org/

Script extracts taken from the November 2015 draft (credited to Neal Purvis and Robert Wade with revisions by Paul Haggis) available here: http://www.dailyscript.com/scripts/Casino-Royale.pdf