Book Review: A Spy Like Me

A Spy Like Me is that rare achievement, being both an addictively readable thriller and a work of great Literature (with a capital L). To the list of literary thriller writers begun by Fleming, which included Poe, Hammett, Chandler, Ambler and Greene, we can now add another: Sherwood.

It took 50 years after first appearing in print for Ian Fleming’s James Bond page-turners to be widely considered ‘literature’ (with or without the capital L, which we’ll come to momentarily).

Starting in 2004, Penguin began to issue the fourteen books under their ‘Penguin Modern Classics’ imprint, signalling to a wide audience that these were more than disposable pleasures. Of course, those of us who were already Fleming aficionados knew all along about their literary value. Even so, when I was reading English at university in the first years of the new millennium I still felt like I had gotten away with it whenever I dropped Fleming into an essay without it hampering my mark.

It doesn’t help the case for the literary status of the Bond books that one of Fleming’s most self-deprecating remarks about his own books is also one of his most quoted:

“They are written for warm-blooded heterosexuals in railway trains, airplanes and beds.”

The remark appeared in his essay How to Write a Thriller, which was reproduced in various iterations in various different publications between 1956 and 1964, which is perhaps why it’s often taken as read.

Was Fleming’s disingenuousness a defence mechanism? Was it really just armour against criticism? Did Fleming really believe the Bond books were disposable pleasures, to be valued little more than pornography (which is precisely how his wife thought of them)?

Taking Fleming’s words as read would mean conveniently ignoring the fact that, even in Fleming’s lifetime, his audience was much broader than he laid claim to. For a start, some of the Bond books’ biggest champions were resolutely not heterosexual. Fans included literary writers like Christopher Isherwood (Goodbye to Berlin) and W H Auden (‘Stop all the clocks…’), not to mention the person most intimately involved with getting Fleming’s works to the public, his editor William Plomer. Plomer was a successful author in his own right and someone Fleming wrote admiring letters to as a young man.

Older gay men were Fleming’s mentors - and some of his most voracious readers. So much for being written to please the appetites of merely heterosexuals. But what about Fleming’s claim - in the same essay - that the target of his books was not the head or heart, but “somewhere between the solar plexus and, well, the upper thigh”?

It’s perfectly possible - whatever one’s sexual orientation - to read a Bond novel solely for its more, well, obvious pleasures. But even the so-called ‘weaker’ novels contain stylistic flourishes - in narrative, diction, description, dialogue - which make them deserving of serious scrutiny, should one wish to bring one’s more critical faculties to bear.

Despite the self-deprecation in How to Write a Thriller, Fleming did acknowledge that he aspired to Literary heights, citing a list of writers who produced “Thrillers designed to be read as literature”, which included Edgar Allen Poe, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Eric Ambler and Graham Greene. All of these are comfortably considered to be Literary in the present day.

What makes something Literature over literature is, of course, highly subjective. But in most people’s minds, Literature is something which has lasting merit. That is, it can be read - and re-read - over and over again and it will still speak to audiences long after its first readers are no longer here. A work of Literature may have a great plot but it also has to have a thematic richness; it’s ‘about’ something deep and universal. Literature speaks to a broad range of people, whatever their individual characteristics and circumstances.

By that yardstick, A Spy Like Me is Literature. But that never gets in the way of it being an addictively readable thriller. If anything, the literary qualities actually heighten the tension.

Fleming identified getting the reader to turn over the page as the “essential dynamic of the thriller”. Sherwood has taken him at his word. A literal ticking clock shapes the narrative: our heroes have six days until a major terrorist attack wreaks havoc. But the book is also about ticking clocks - and our relationship with time more universally. In A Spy Like Me, chronology is story and story is chronology. Far more than a narrative gimmick, time - and being ‘out of time’, in multiple senses of the phrase - is the major thematic concern.

This is a Bond book in which a principal protagonist wears multiple watches, not merely because the plot demands it but because the watches foreground the theme and it provides an emotional hook which pays off to devastating effect midway through.

The economy of Sherwood’s prose is quite breathtaking. The novel could easily be twice the length and would still feel tightly-constructed. This is a book with a lot of characters, settings and plot threads - and that’s even before you get to the multiple layers of meaning. The dialogue is delectably pithy (redolent of Raymond Chandler in its quotability).

It’s not until you’ve read the book a second time that you realise how fleet-of-phrase Sherwood has been, outwitting you at every turn. To borrow the horological imagery of the book’s opening sentences, it’s only when you can visualise the whole machine that you can see Sherwood’s cogs, wheels and pins in operation.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves: during the first reading you’ll be too on edge to notice Sherwood’s deftly manoeuvring you through her labyrinth, even though everything is right there, hiding in plain sight.

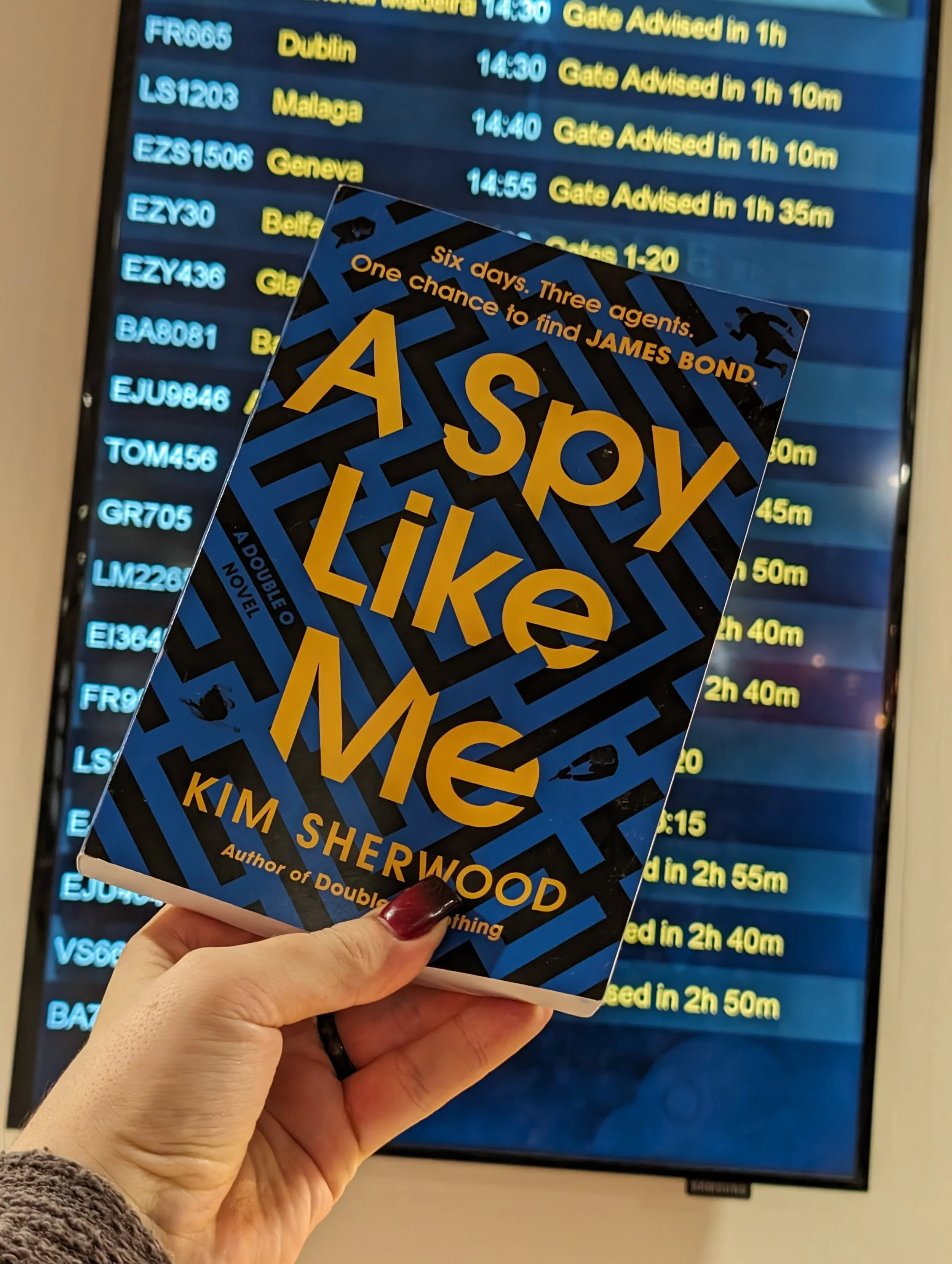

The most intricate of her books by some margin, Sherwood has shared how she nearly “lost the plot” in a literal sense while in the final stages of writing. She simply couldn’t see the wood for the trees or, to use an analogy more in-keeping with the book’s Cretan setting, couldn’t find the thread to help her out of the maze. It’s fitting that the US cover features a literal labyrinth, a stylistic depiction of a major set piece (albeit in the maze of a free port, not a Minotaur). The UK edition is less literal, but uses a maze-like map of Venice (another important setting) to convey the same idea.

Fortunately for us, Sherwood made it out. The resulting book is a joy to read; even when you feel like you might be getting a bit lost, you never doubt you’re in a very safe pair of hands. You won’t feel cheated, or stupid, when you don’t see the twists and turns coming.

Sherwood targets our heads, then, as well as our hearts and the regions between our upper thighs and our solar plexuses. Not that these parts of our anatomy get short shrift; this is a book which will both break your heart and cause your blood to warm, often within the turn of a single page.

Sherwood opens A Spy Like Me with an epigraph taken from Fleming’s You Only Live Twice (in turn borrowed from Jack London): ‘I shall use my time’. More often than not, when I read an epigraph like this, I can’t help feeling like the writer is being pretentious. In this case, nothing could be further from the truth. Sherwood’s choice of quotation could not be more apt, distilling both the theme and plot of the novel in five punchy syllables.

Let’s not make the mistake so many critics made with Fleming by waiting 50 years to appreciate what we have here: a tremendous thriller which is also great Literature.

In conversation with David Lowbridge-Ellis, Kim Sherwood uncovers everything you need to know about the writing of the addictively enjoyable Bond thriller, A Spy Like Me. Taking us behind the scenes, nothing is off limits as Kim shares her story inspirations, her writing process, how she feels about people who say having diverse Double Os is merely ticking boxes and a lot more. David and Kim even take time to pore over 004’s choice of swimwear (it’s a tough job and David and Kim are the ones to do it).

To enjoy a week’s worth of exclusive content, click the image below: