Batman and Bond: the queer heroes we deserve

In the dark days of my early twenties, I fell out of love with Bond and poor Batman had to shoulder the responsibility of being my queer role model. Now that I’m nearly 40, staring down like a brooding gargoyle at my impending birthday, I’m wondering where the Batman and Bond influences end and the real me begins?

This article is also available as a podcast:

Nearly half a lifetime ago, I wrote my undergraduate dissertation about Batman. My specific focus was the grammatical choices used by the writers in the initial run of Detective Comics in which Batman featured (from 1939 until 1940). It was more fun than it sounds, both to write and - it turns out - read. Whoever ended up assessing my Batman dissertation thought it deserved a high mark and it helped secure me a First Class degree in English literature and language. The end result almost made up for the heartache and headache. While I enjoyed the process of researching and writing on some level, I’ve never been one to do a half-cocked job of anything, sometimes to the detriment of my well-being. This is something I have in common with both Batman and Bond: when they have a job to do, they give it their all.

I poured my heart and soul into that dissertation. I was really going through it at the time: I was in the depths of depression, although it would take me several more years for me to seek medical confirmation and professional assistance.

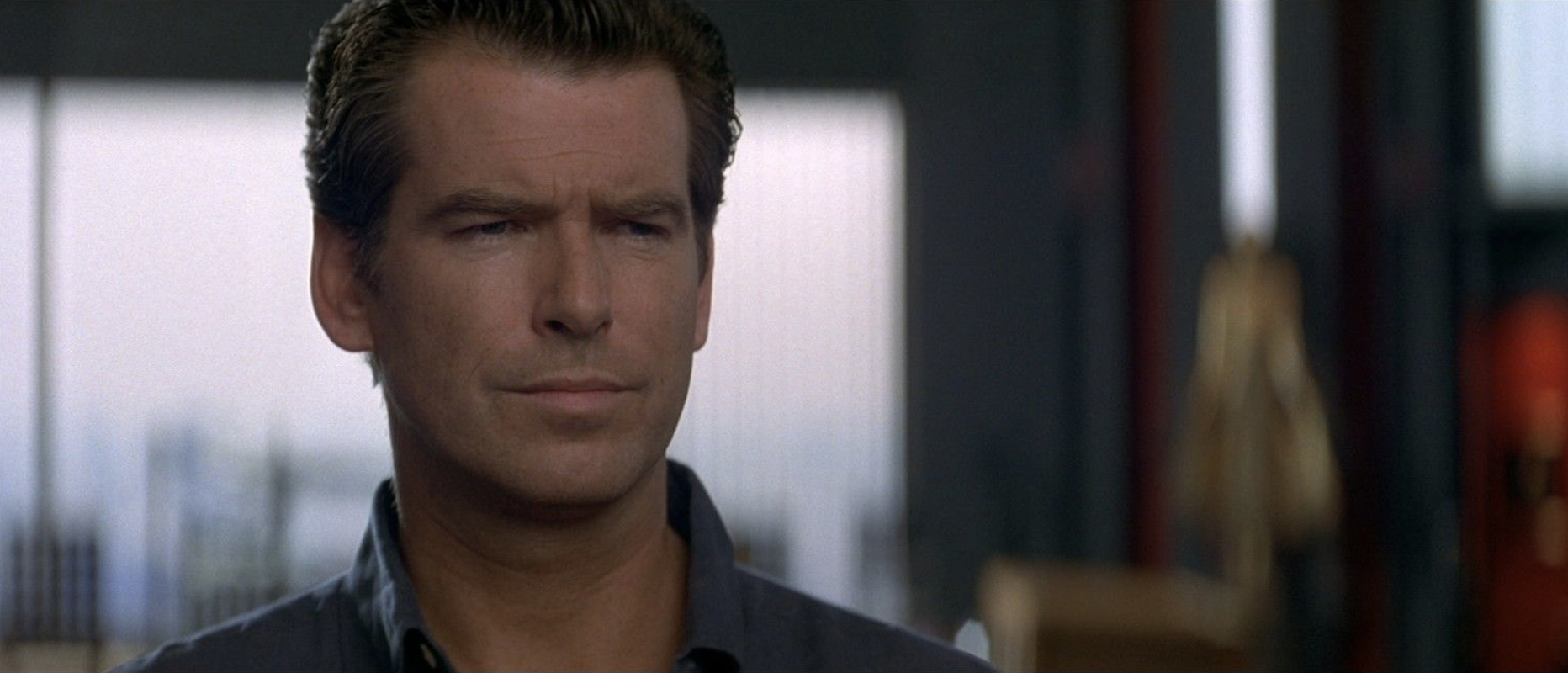

But in his own way, Batman helped me through the final year of university and I graduated in the summer of 2003. Seven months previously, Die Another Day had been released and it had contributed to my temporarily falling out of love with Bond. I had known I was gay - but nowhere near ready to fully admit it to myself or anyone else - for some time. I didn’t see myself in the character of Bond and Die Another Day in particular. Re-viewing the film recently was a rehabilitative experience, for me and the film. Stripped of its heteronormative surface, it’s actually an energising watch and viewing it through different lenses helped me to see what I had initially missed: a deeply queer story masquerading as something more crowd-pleasing.

My Batman dissertation was entitled ‘A search for subversive ideology’ and perhaps it was researching and writing this which turned me on to looking deeper at popular texts. If Die Another Day had been released in 2003, after I completed my dissertation on Batman, perhaps I would have looked on it more kindly and my relationship with Bond would never have gone through a rough patch. Fortunately, when I was ‘on a break’ from Bond, Batman was there to pick me back up.

While Bond was my first childhood love (if memory isn’t playing a trick on me, my first Bond film was Goldfinger with my grandparents when I was six years old), Batman followed soon afterwards. Repeats of the 60s series starring Adam West were on TV all the time. The summer I turned seven, the older boys who lived next door didn’t shut up about how amazing Tim Burton’s Batman film was. To their credit, they let me have some of the trading cards they had duplicates of and I made up a version in my head of the film’s story based on the photographs of Michael Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Kim Basinger, et al on those cards. I finally saw it on BBC1 on Christmas Day 1991 and I recall my dad pointing out how improbable it was that Vicki Vale could survive such a rapid fall from the tower in the film’s climax. I didn’t care though: I was enraptured with the whole thing. I was even more taken with Batman Returns, a film which I feel intimately connected with even now. For my thirteenth birthday, my parents took me and two of my closest friends to the cinema to see Batman Forever and I can still remember the exact moment I saw Chris O’Donnell appear on screen. It turns out I wasn’t the only gay boy for who this was a moment of awakening. It was only years later that I read confirmation that Forever’s director, Joel Schumacher, was gay himself. In hindsight, it’s pretty obvious and very visible on the screen!

Throughout the nineties, we were treated to arguably the greatest incarnation of Batman, not in live action, but animation. Rewatching episodes of The Animated Series on the recent Blu-Ray release confirms what I felt at the time: even when others let us down, Batman is the queer hero we deserve.

Interesting role models

Although both Batman and Bond are ostensibly straight - and have both had words put in their mouths by predominantly, but not exclusively, straight writers - both characters make it easy for queer people to identify with. Writing in 2016, gay critic and Batman expert Glen Weldon argued that although it was rarely intentional on the part of the characters’ storytellers, “Gayness is built into Batman”. I would contend that Bond is the same.

In my queer re-view of No Time To Die, I wrote the following:

For me, Bond is a palimpsest, a piece of paper (or, if we were in Ancient Greece, a wax tablet) which has been reused time and again with traces of earlier versions showing through.

The same could be said of Batman, only more so: there are so many different versions - including at least four different cinematic iterations in the last decade - that it’s difficult, and I would argue, not desirable, to separate them. Rather than adhere slavishly to the demands of ‘canon’ like the Marvelverse, it’s better to see them all as all the same, but somehow different: Bale-man, Batfleck, Lego Batman and Battinson (personally I prefer R-Patz-man and will continue to use it while the portmanteau is still in flux).

As with Bond, almost everyone - whether they have ever seen a Batman film or not - knows the basics: a kid who watches his parents get murdered in front of him channels his grief and anger (and considerable wealth) into protecting people less fortunate, in the somewhat naive but inspiring hope that history won’t repeat itself.

In almost every version, Batman is more or less traumatised by his upbringing. And while most queer viewers will not have suffered a sudden traumatic event as Bruce Wayne did, the slow water torture of self-shaming has left its mark on most of us. While many are quick to point out that the Daniel Craig era brought us a more existential Bond than any we had before, psychoanalysis has been increasingly pushed to the forefront since GoldenEye took postmodern swipes at the character.

Bringing psychology into it.

After nearly 70 years, it’s never been easier than it is right now for queer viewers to relate to Bond, although Batman has been making identification easy since his first appearance over 80 years ago.

In most Batman stories, the central concern is the lead character’s search for identity. It’s an immature story, in the best possible sense. How many of us, however old we are, whether we are queer or not, can genuinely say that we really know who we are? Finding out who we are is a lifelong process, however we begin.

Like Bond, Batman is an orphan, something I explored in my queer re-view of Tomorrow Never Dies:

Orphaning your character is, according to John Mullan, “fictionally useful” because it means the character will have to find their own way in the world.

The absence of parents allows writers more creative freedom - and to imbue their characters with greater uncertainty. Invariably, this means they have to, like many queer people, find their own family. Batman’s family expands and contracts, with the near-constants being Alfred and Gordon. Similarly, Bond’s family is more often than not limited to a small core of M, Q and Moneypenny, with Felix Leiter popping up whenever there’s a faintly legitimate reason.

While Batman tends to work more in the literal shadows, both characters’ victories are cloaked in mystery. The whole double life thing comes into play here, as it does with most characters who possess queer appeal. In theory, their need for secrecy might appear to be a choice. But they are both defined by their careers, whether they like them or not. If anything, they are no longer leading double lives but have had their more respectable sides subsumed into their professional alter egos. Batman is pretending to be Bruce Wayne, James Bond is pretending to be a recognisably human being. Dr Jekyll has been taken over by Mr Hyde, and is all the better for it?

I’m not so sure. The “soul erosion” Fleming refers to in the first paragraph of Casino Royale takes its toll. Bond may do much of his best work in sunnier climes - Jamaica, the Bahamas, Cuba - but it doesn’t give him a sunnier disposition.

I was a fairly insular and moody child, mostly uninterested in going out and socialising, more often than not preferring to sit inside by myself and read. I had delusions of dolour, not unlike the titular character of Tim Burton’s early short film Vincent, who spends a large proportion of his days imagining up reasons to explain why he feels miserable, taking inspiration from reading Edgar Allan Poe short stories.

In my case, I took inspiration from Batman and Bond, self-indulgently imagining I had more in common with these tragic characters than I really did.

My childhood lack of Vitamin D didn’t do me any permanent damage though. A steady drip of Batman and Bond nourished me… or was it a form of slow poison, reinforcing my delusions? I’m still not sure. It’s something I’m working through with my therapist. I’ll keep you posted!

When things got really bad with my mental health in my early twenties, I developed a serious crush on another fictional character who is arguably a progenitor of Batman and Bond: Shakespeare’s Hamlet. My crush on Hamlet rapidly developed into an obsession - as these things usually do with me. One particularly depressed Christmas Day, I read the whole four hour play (with deleted scenes) twice, cover to cover.

Batman is routinely compared with Shakespeare’s narcissistically mopey but endearing hero. Critic and writer Kim Newman says that the multiple interpretations of Batman are the strength of the character: “It used to be said that every generation had its Hamlet, and now I think every generation has its Batman.”

In 1989, film critics made Hamlet comparisons after seeing Dalton’s take on Bond in Licence To Kill and Daniel Craig’s portrayal in Quantum of Solace led many reviewers to do the same. Andrew Pulver in the Guardian called Craig’s Bond “a Hamlet for our times” and Paul Whitington in the Irish Independent stated that “Craig turned a cartoon into Hamlet” (perhaps unaware of the fact that Batman The Animated Series had given us a cartoon Hamlet character nearly two decades before). Whitington did however nail why many of us find Craig’s Bond so relatable:

Craig's Bond, though, is all too human. There's something the matter with him, his careers across the world seem like a cry for help. He's tough as nails but none too thrilled about it, and his unhappiness lets his audience in.

A 23 year old Ben Whishaw in the Old Vic’s 2004 Hamlet.

In the 2016 RSC production of Hamlet (below), Paapa Essiedu was not afraid to lean in to the queer aspects of the character.

There are many reasons for queer people to be unhappy. We are disproportionately affected by mental health issues and not because of who we are, but how we are made to feel about who we are. It shouldn’t be our problem to solve but many of us feel a responsibility to make society see the error of its ways, using our insights into what it’s like being marginalised to make the world a better place. But doing things ‘for the greater good’ can be utterly exhausting and I think it’s this, more than anything, that makes it easy for me to relate to Batman and Bond.

Batman rarely takes the shortcut for anything and he never gives up. For me, his perseverance is his most admirable quality. In almost all of his iterations, Batman has grit. Determination. Call it what you will. Sometimes he convinces onlookers that saving the day was easy, although he doesn’t spare us - the audience - from seeing what it takes out of him. Batman makes sacrifices, time and time again, often for people who will never thank him.

On film, Bond is usually better at concealing his exertions than Batman. His determination looks more like gumption at times. The guns are pertinent here. Bond is almost always armed, whether with his signature Walther PPK or another efficient tool of his trade. Although there have been occasions where Batman has wielded guns, this is not the norm. Perhaps this is because guns uncomfortably trigger (no pun intended) memories of his parents’ murder. Or perhaps it’s because he likes to make life difficult for himself.

But armed or not, Bond can be just as determined as Batman. When all looks lost, he’ll find the energy to continue, especially in the more masochistic Fleming finales and the films where we’re afforded glimpses beneath the stoic armour.

Twenty years ago, I concluded my dissertation on the language of Batman comics by arguing that the same cultural commentators who condemned the Batman character for his socially unacceptable actions (such as ‘accidentally’ letting a murderer fall into a vat of chemicals) were the same people who were all-too-willing to wage wars on dubious pretexts. The Iraq war was clearly at the forefront of my mind. I’ve never been a fan of hypocrisy.

Even so, Batman is hardly - in any sensible person’s estimation - a perfect role model, which is probably why so many of us warm to him.

Repeated studies have shown that focusing a lot of our attention on high-achieving role models - real or fictional - by itself does not give us sufficient motivation to improve our lives. The closer to perfection our role models are, the more we are likely to measure ourselves against them and constantly feel like we are falling short. Where role models can have more of an impact is where they do great things while also demonstrating their vulnerabilities and failings.

In an interview with 007 Magazine, Timothy Dalton rejected the idea that Bond should be a role model because “he’s a man riddled with vices and weaknesses as well as strength.”

I can see his point. But for those of us who grew up feeling like our very existences made us vice-ridden and weak, but still found the strength to hold our heads up and not just look out for ourselves but others too, he’s not a bad place to start. The rest is up to us.

I am not, like Batman, vengeance. I am not, like Bond, a blunt instrument. I am partly them, but mostly my own person.

Who am I again?

If you enjoyed my ramblings about Batman, you may be interested in my piece for Gayly Dreadful about my love for Batman Returns:

https://www.gaylydreadful.com/blog/pride-2020-sickos-never-scare-me

Many of the Bond-related issues touched on in this piece are addressed more fully in my various queer re-views, linked to throughout this piece.